Alexander Daniel

Alexander Yulyevich Daniel (born March 11, 1951, in Moscow) is the son of Yuli Daniel and Larisa Bogoraz. From 1968 to 1989, he worked as a programmer in various scientific institutions. In 1978, he graduated from the Mathematics Department of the Moscow State Pedagogical Institute (MGPI). In the 1970s and the first half of the 1980s, he was unofficially involved in information work within the human rights movement, as well as with issues of Soviet history: from 1973 to 1980, he participated in the publication of the “Chronicle of Current Events”; from 1976 to 1981, he was a member of the editorial board of the uncensored historical collection “Pamyat” (Memory), dedicated to the problems of Soviet history.

Since 1989, he has been a member of the Working Collegium (board) of the Memorial Society. Since 1990, he has been a staff member of the “Memorial” Research and Information Center (NITs) in Moscow and a member of the NITs Council. From 1990 to 2009, he was the head of the “Memorial” NITs research program on the topic “The History of Dissent in the USSR, 1950s–1980s.” Since 2009, he has been a staff member of the St. Petersburg “Memorial” Research Center, working on the “Virtual Gulag Museum” project.

— How did you enter dissident circles? At the time of the Sinyavsky-Daniel trial, you were only 15 years old.

— I wasn’t even 15 yet.

— Was this event a turning point in your self-determination? Or had you already come into your own in that regard by then? Or did something else later define your future biography?

— How can a person be fully formed at 14? Of course not! But if you are asking about my views on what was then called by the strange phrase “Soviet reality”…

— Yes, what was that trial to you at the time? Was it a surprise?

— It certainly wasn’t a surprise to me. Because a year earlier, in January 1965, my father had told me about his underground writing and gave me his novellas and stories to read. I think he did this quite consciously because he understood that an arrest was coming, and he didn’t want it to be a complete shock to me. And it really wasn’t a shock.

As for my views on the world around me, they formed somehow on their own, gradually. Mostly from reading various things. It wasn’t a case of someone purposefully raising me. My parents generally tried not to impose their ideas about the world on me. So, I—initially a perfectly normal Soviet child, who took all the ideological nonsense we were fed in school very fervently and sincerely—gradually shed this nonsense on my own. Primarily through reading and some—probably rather superficial—reflections on what I read. They probably weren’t even reflections, but a gradual realization that all this talentless official rhetoric was incompatible, how should I put it, in its “tone,” with genuine culture, with my favorite poems, for example—and not just with Brodsky or Pasternak (I was already starting to read them then), but even with Mayakovsky and Bagritsky.

And, well, I couldn’t help but hear the different conversations adults were having. My parents’ social circle was the Moscow intelligentsia, both in the humanities and in science and technology. In those days, practically everyone in that milieu was liberal- and opposition-minded. Of course, I heard things, certain judgments, and somehow I digested it all.

And there was no dissident circle in existence yet. At least not in that generation, my parents’ generation. Younger people, the post-war generation, were already forming dissident cliques: “Mayakovka,” “Sintaksis,” SMOG, and so on. My parents and their friends had some contact with a few of these cliques, but it was quite superficial. They themselves mostly belonged to the previous generation; they had lived through the war as fully conscious adults, many had been to the front, some had done time after the war, and some had parents who had been imprisoned. Their youth coincided with the post-war stupor, the decree on the journals *Zvezda* and *Leningrad*, the VASKHNIL session, the campaigns against genetics, cybernetics, cosmopolitanism, and theater critics, and the “Doctors' plot.” So the 20th Party Congress didn’t reveal anything new to them, unlike the next generation, whose “eyes it opened.” And the older ones became “dissidents” gradually, in the course of various events: the Pasternak affair, the Brodsky trial, the Manege scandal, and so on. Everyone read samizdat, everyone listened to Okudzhava, Vysotsky, and Galich. And for some, the Soviet regime itself made them dissidents, like my father, for instance, when they jailed him. Accordingly, his and Andrei Sinyavsky’s friends and acquaintances—and this was a very wide circle, as my father was a very sociable person—almost to a man, they turned into dissidents, that is, they began to show their dislike for the Soviet authorities not just in their opinions but in their actions. The Sinyavsky-Daniel affair—the arrest, investigation, and trial—became a powerful catalyst for the consolidation of many different circles and groups into a single dissident milieu. As a teenager, I found myself inside this process of consolidation—in the sense that I observed it from the inside. Our home simply became one of the centers of this consolidation after my father’s arrest, and I was immersed in this stew.

Alexander Daniel, 1974.

— When did you enter this circle, no longer as a young man—a witness—but as a participant?

— Well again, what does it mean to be a participant? I traveled for visits with my father in the camp—and so I was involved in the exchange of information between the Mordovian camps and Moscow, especially when my mother was also imprisoned [after participating in the demonstration on Red Square on August 25, 1968] and I traveled for visits alone. So, in a sense, I was already participating a little bit in the late sixties. Then, after 1970, when my father was released, I continued to participate in this information exchange for a while: a few other relatives and friends of prisoners, like Arina Ginzburg, and I—we manned the communication channels. But you still can’t call that systematic work. The systematic work began later—in the summer of 1973. That was the *Chronicle [of Current Events]*.

— Which by that time had already been coming out for several years. So you joined its work...

— The *Chronicle* had been coming out since the spring of 1968. And again, since I knew and was friends with Natasha Gorbanevskaya, who was the first publisher of the *Chronicle*, I would sometimes bring her things, some information for the *Chronicle*. Especially since Natasha had this way about her. I’d show up and tell her something: “Natasha, I think this would be good for the *Chronicle*.” She would say: “What, can’t you write? Sit down and write it!” I would sit down and write. And I wrote a few such reports: maybe five, maybe ten. Is that participation or not? The *Chronicle* had dozens of such “occasional correspondents” at the time. No, I still can’t call that participation.

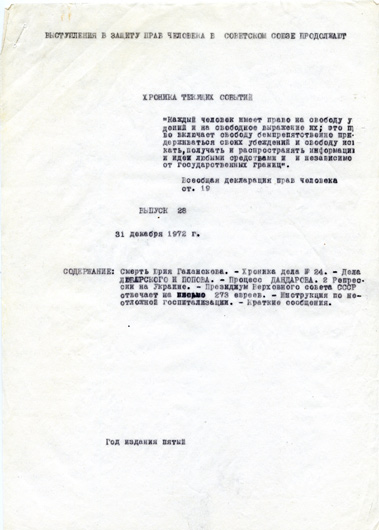

But in the summer of 1973, when the *Chronicle* had temporarily stopped publication (the last issue before the hiatus came out in November 1972), somehow… I have to say, by that time I didn’t even always read the *Chronicle*, not every issue and not in order. But then it stopped coming out—and I and many others like me felt a kind of dreary emptiness, that such a publication was gone. And a close friend of mine, Marik Gelshtein (he passed away long ago), said to me: “There’s a group that’s ready to continue it and wants to contact the people who used to produce the *Chronicle* to ask for, as they say, permission and a blessing. Can you look into it somehow?” I went to Tanya Velikanova and said: here’s the situation… She said: “Well, give it a try, guys. It really is time to resume the *Chronicle*.” And she passed me the materials that had accumulated during the pause. This was August or September. It then turned out that all the talk about a group was empty, and that it all boiled down to just Marik. And the two of us started working on three issues at once—28, 29, and 30. Retrospectively, as if filling the gap. We worked on them for a very long time because we were still inexperienced and the work was slow. But somewhere around February 1974, the “skeletons” of these issues were ready, and I gave them to Tatiana. Tatiana, as I later learned, gave them to Sergei Kovalev to polish. Because, I repeat, we were inexperienced and these were rather raw “skeletons.” So the resumption of the *Chronicle* and the release of three “retrospective” issues were announced only in early May 1974. And from then on, I actively worked on that bulletin for some time.

Alexander and Yuli Daniel, 1972.

— The background to these events, from the summer of 1973 to February 1974, was a fateful time for the dissident movement and for modern Russian history in general. Late 1973 was a crisis linked to the Yakir-Krasin trial. February 1974 was the exile of Solzhenitsyn. Was your joining the *Chronicle* in any way connected to this background?

— Well, yes. There was a sense that it was indeed a crisis, and therefore it had to be overcome, to find a way out of it. Those were our motivations. I wasn’t really eager to be a participant in anything, but that’s how it turned out.

— You mentioned three issues. Did you step away from the *Chronicle* after that?

— No, for a few more years, I worked in the circle of people who prepared and published it.

— Who made up that circle in those years?

— Sergei Kovalev, Tanya Velikanova, Sasha Lavut—those are the ones I knew. (I didn't know everyone: Tatiana was an excellent organizer, and she had several teams.) Later, in 1977 I think, in the fall, Tanya introduced me to Lenya Vul, and for three or four years I worked mainly with him. Well, my friend Mark Gelshtein also continued to participate in the work on the *Chronicle* texts until his death in 1979. In addition, several of my close friends also joined the work: some episodically, others systematically. Natasha Kravchenko, my first wife’s friend; Yura Efremov (well, he actually used to gather some information for the *Chronicle* even before me); Andrei Tsaturyan and Gena Lubyanitsky—my friends since school. I graduated from a mathematics school, the well-known “Second School” in Moscow, and my social circle was mainly connected to my former schoolmates (Marik, by the way, was also a graduate of that school, just from an earlier class). All of them—well, perhaps with the exception of Natasha Kravchenko—were not dissidents in their public behavior in the sense that the word is given today: they didn't sign petitions, participate in protest actions, or hang out in dissident salons. They were, rather, part of the “surrounding social milieu,” the layer of sociocultural support for dissidents. I think they had (and still have) much more significant professional interests; they were all successful in their professional fields: Andrei Tsaturyan is a biologist, already very well-known back then; Yura is a poet, a translator from Lithuanian, and for the *Chronicle* he mainly did reviews of Lithuanian samizdat journals; Natasha is a programmer; Gennady is an oil economist. But they were ready to work on the *Chronicle*—and they did.

— You must have been under surveillance by the “organs” from a young age. Did you feel this attention? Did you have any run-ins with the KGB?

— There are a few funny stories here, which have perfectly objective documentary proof. Yes, there was a certain amount of attention. Right now, studying various informational memos from the KGB to the Central Committee from 1967–1968, I sometimes stumble upon my name in there with astonishment—a total greenhorn, a schoolboy. For some reason, they found it necessary to mention me in their reports “upstairs” to the Central Committee: what the tenth-grader Daniel said in such-and-such company, where he went… (Laughs.) I was amazed by this fact. There was another funny story about when I was applying to the university in Tartu in 1968. I did wonderfully on all the exams there, strangely enough, even though I was a major loafer, but for some reason I passed the exams very well…

I was applying to the physics and mathematics department. But, naturally, I got to know everyone in the Russian philology department, the entire “Tartu School”—both the young people around the school and the respectable figures, including Yury Mikhailovich [Lotman]. In short, it seemed I was admitted, but then it turned out I wasn’t. A very elegant operation was carried out, as a result of which I didn’t get in. Roughly speaking, it went like this. There were 15 spots in the Russian section of the physics and math department. I was second on the list, and four others were non-competitive admissions. That means I was sixth, counting those non-competitive ones, and second in the competitive pool. Suddenly, it was announced that the number of spots in the Russian section was being reduced to five. And I was sixth. Well, I moped about it for a bit and took back my documents. And as soon as I took them, they restored the original number. And it turned out they had told the other applicants not to rush to take their documents back. And no one did, and everyone who was supposed to get in, got in. But I took mine back—and was left out in the cold. You have to admit, it was elegantly done! I later went to the rector to sort things out, but the train had already left the station. And the rector almost directly confirmed to me that this came from the Committee for State Security.

In the end, several years later I enrolled in the evening division of the MGPI, the math department, and graduated from it. I graduated in 1978.

But! Despite stories like these, despite my name popping up in KGB reports to the Central Committee, despite the occasional searches of our home—it turns out that an operational surveillance file was opened on me only in 1977! And I, by the way, had been involved with the *Chronicle*, as I already said, since 1973. I learned about this—that the surveillance file was opened on me four years later than it should have been—only after 1991. What could that mean? Maybe that they were also working half-heartedly? Well, they weren't a super-informed or super-efficient agency. But that's fine, I'm not complaining (laughs).

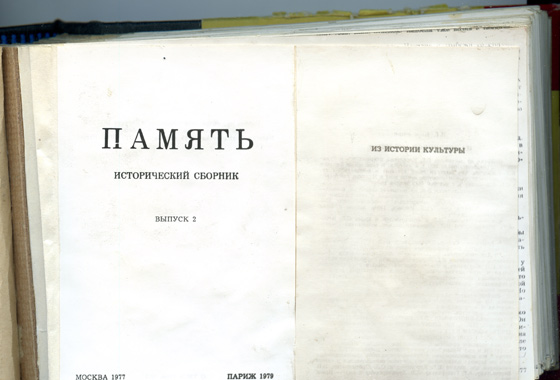

— By 1978, you were already taking part in unofficial historical endeavors. I’m referring to the *Pamyat* (Memory) almanacs, which were unique against the backdrop of the samizdat of the time, because it was perhaps the only enterprise connected with academic science, as much as that was possible, with restoring historical memory, with serious historical research, and at the same time an uncensored initiative. That is, an attempt to revive an uncensored historical science. And, as I understand it, you played a rather important role there.

— Well, I played some role. But far from the most important one. There were people who did much more.

Issue No. 2 of the historical almanac Pamyat

— You, in particular, wrote the “From the Editors” preface to the first issue.

— That did happen. Yes, I wrote it…

— So, in a sense, you were the publication's ideologue.

— Oh, no, of course not. We had discussed all the main points beforehand with colleagues: with Arseny Roginsky and, I think, with Seryozha Dedyulin. I drew up a draft of the text, then Dedyulin and I edited it, and Arseny and I finalized it.

— Please tell us more about *Pamyat*!

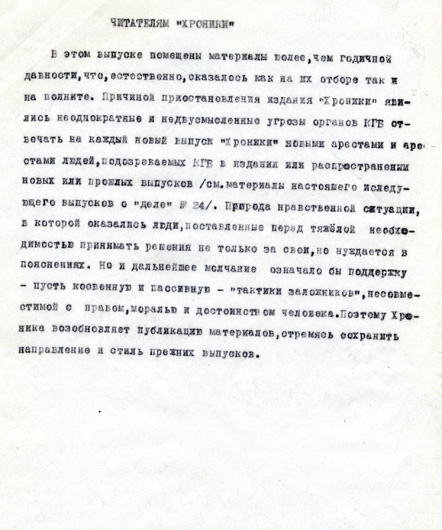

— You know, just recently I read a very interesting work by the Omsk-based researcher Anton Sveshnikov about the historiography of *Pamyat* (it hasn't been published yet, it only exists in manuscript form). It's a large, well-founded work. And now I’m a little afraid to answer your question, because I'm no longer sure what I remember on my own, and what I’ve read about myself and my friends in Sveshnikov’s work (laughs). Well, I can just name the people, the circle of people who came up with it and were mainly involved. I was still a little bit off to the side of the center of it. First and foremost, that was Arseny Roginsky, Alexander Dobkin, and Sergei Dedyulin—from Leningrad. Two other Leningraders—Valery Sazhin, a bibliographer from the Public Library, and Felix Perchenok, a schoolteacher. The Moscow part of the editorial board was me, Alexei Korotaev, Dmitry Zubarev, Kostya Popovsky (the son of the writer Mark Popovsky), and Larisa Iosifovna Bogoraz, my mother, who also actively participated in the general work. I've surely forgotten someone… Oh yes, Boris Ravdin from Riga was close to the editorial board. And, of course, Mikhail Yakovlevich Gelfter; he wasn't directly involved in the work, but he was, like Borya Ravdin (and in fact like many other authors of *Pamyat*—David Mironovich Batser, Veniamin Iofe, Yakov Solomonovich Lurye, Raisa Borisovna Lert, and a whole range of others), what you might call part of the “reference group.”

— How did historical topics become so important to you, a person with a non-humanities education?

— I always had an interest in the humanities. And I probably would have become a humanities scholar, if not for the conviction—a naive, youthful, maximalist conviction—that a professional humanities scholar had no place in Soviet humanities, except perhaps in linguistics. I was a rather well-read young man; I read, among other things, all sorts of specialized works on history, philology, and so on. Of course, I lacked important professional skills: archival work skills, the habit of working in a library. To be honest, I never did acquire these skills in the necessary measure. And I still feel their absence acutely. And when I started working on *Pamyat*, I fell in with a group of people who were far more professionally advanced than I was. Though it must be said, of the people I named—who was actually a professional historian? Only Roginsky! And even he had a degree in philology, not history. But that was the Lotman school, which provided a wonderful historical background. And Sazhin too—he was a bibliographer, after all. The rest were tech-educated, like me.

— A distinctive feature of *Pamyat* was that your contemporary period was also included in the scope of description. In particular, it published Igor Melchuk's memoirs about his contacts with the KGB, and a discussion of Anatoly Marchenko's *My Testimony*. In other words, you already realized back then that this period of Russian history, connected with the dissident movement, would require its own description and that materials for it should be collected.

— Yes, that’s absolutely right. And there were people among us who were actively engaged in this. The famous archive of contemporary samizdat, which Sergei Dedyulin purposefully collected… well, Dedyulin wasn't the only one: Sasha Dobkin actively helped him with it. And all of us pitched in a little. There was a very clear understanding that this was for the future, that this collection would become a historical archive in the future. Seryozha started collecting it, I believe, even before *Pamyat* began. It's funny that from a certain point, some Moscow samizdat authors, compilers of almanacs and collections who were somewhat in the know, began to consider it mandatory to pass one copy of everything they produced “for the Leningraders” (Dedyulin himself was not well known in Moscow for a time). It became like submitting a mandatory deposit copy to the Lenin Library back in the day. In particular, from the mid-70s, the *Chronicle* gave Dedyulin's collection one copy from the so-called "zero-th typing," that is, from the first print run of the manuscript.

HTS No. 28

HTS No. 28

— Was it lost or has it been preserved?

— It has been preserved. It’s now at Memorial. What survived of Dedyulin’s archive after the search of his home in March 1979 was preserved by Dobkin and a few other people and later transferred to Memorial in Moscow. The remnants of Dedyulin’s archive are now stored at Memorial—it's the so-called Leningrad Fund, one of the most interesting samizdat archive collections I know of.

And regarding the connection between history and the present: we even made a kind of symbolic gesture—we dedicated the first issue of *Pamyat* to two staff members of the *Chronicle of Current Events*, Sergei Kovalev and Gabriel Superfin. As it was said—in recognition of their exceptional contributions to the work of collecting and preserving the facts of the past and present.

— They were both in prison at the time.

— Yes, they were both in prison at the time. It was, of course, a significant dedication.

And in the third issue of *Pamyat*, if I'm not mistaken, there was a text from the editors—a congratulation to the *Chronicle of Current Events* on its 10th anniversary; that was in 1978. In that text, the idea of the complementary nature of our two publications was expressed, though implicitly: that since the Resistance of 1968–1978 was also becoming history, the *Chronicle* was also a future historical source. In a sense, the *Chronicle* was the future of *Pamyat*. And Arseny put it even more simply, without any metaphors: “The *Chronicle* documents what happened after 1968, and *Pamyat* documents what happened before the *Chronicle*.”

— So the dividing line was drawn at 1968, it turns out.

— Yes, exactly. And, say, the “Kolokol” case in 1965 in Leningrad—that was still the domain of *Pamyat*, which is why there was an article by Veniamin Iofe about that case in the very first issue. Everything before 1968—that was ours, that’s how we decided.

The editors of *Pamyat*: A. Roginsky, Yu. Shmidt, A. Daniel, L. Bogoraz, V. Sazhin, Ya. Nazarov, B. Mityashin. Leningrad, 1976.

— At what point did it become clear that the period after 1968 had already become a matter of history? In 1991? Perhaps later, or, conversely, earlier?

— I think even a bit earlier, not in 1991. As early as 1989, the idea arose that Memorial would, among other things, study the history of dissidents, and by 1990, I had already begun collecting materials on dissidents and other samizdat for Memorial’s archival collection. Ludmila Alexeyeva gave us her archive, Kronid Lyubarsky gave us his. I’ve already mentioned the “Leningrad Archive.” In general, by the end of 1991, we already had a fairly decent collection on this topic. Now it is one of the most complete in the world and, in any case, the most extensive in the post-Soviet space.

— The end of 1991, if I understand correctly, was marked by a unique opportunity, which didn’t last long—it’s also interesting just how short it was—to access the KGB archives. Could you tell us how long and how deep that opportunity was?

— Of course, to get a thorough answer to that question, you should ask not me, but either Arseny Roginsky, or Nikita Petrov, or Nikita Okhotin. I took part in this access to the KGB archives a little, but very little. And, in my opinion, the turning point here was 1994, when the process reversed, when everything first slowed down, and slowed down, and slowed down, then stopped altogether, and then went backwards. The slowing of this process—that was 1994. A very good and well-thought-out set of access regulations was created, which was initially adopted and then canceled. This regulation was even published in a 1993 issue of *Istochnik*, I don’t remember which month. And then it got worse and worse, and here we are in the current situation, where access to the archives has become extremely difficult.

— My impression is that the window of free access to the archives, including operational surveillance files, existed for literally just a few months around the turn of 1991–1992.

— Operational documentation was formally closed more or less all the time. There was, of course, a moment when all those folks at the GB [State Security] took us for the new bosses, were fawning in every way and extremely obliging. But that really didn't last long, just a few months.

— And to what extent did this opportunity reveal truly unique things, which are now irretrievable and were previously inaccessible? In other words, to what extent was this freedom taken advantage of?

— I must say that I actually have serious doubts about the value of operational documentation for a historian. I have a few thoughts on this, and the main one is this: the pictures that emerge from operational surveillance files, from agents' reports, from wiretaps, from surveillance reports, and so on—this is a very specific view of events. It's a policeman's view, a view through a keyhole. Maybe you can restore some minor facts from these sources, but, my God, not the crucial ones. Much more important, of course, are the regulations—that is, their orders, manuals, and the like. That is truly important and valuable. But what Agent X reports about Subject Y—that’s not very interesting. Or what they overheard by means of the so-called “Letter S measure”—well, they heard something on their rather shoddy equipment. In my opinion, that's not the most interesting part.

— But isn't it an opportunity, a rather unique one, for documenting, if it's, say, a wiretap, some...

— In their language—the “Letter S measure.”

— …yes, some conversations. How, for example, would the real statements and conversations in the literary milieu have reached us, to draw an analogy, if they hadn’t been recorded in the reports of the *seksots* of the 1930s? They would have been lost. So this does have great documentary value.

— The raw materials might still be interesting. But their documents mostly contain summaries: someone reports to someone else about what a third person said. The very selection of what they considered most significant from their police point of view introduces serious distortions. It’s a police aberration of reality. Sometimes, though, there are analytical memos, overviews, reports—not from agents, but from the Chekists themselves; some of them are quite interesting.

— It would be interesting to talk about how much gaining access to these Lubyanka documents changed your perception of the dissident movement, its relationship with the authorities, and its internal problems. Did it force you to look at it differently? How much did this information change your view?

— I haven't really thought about it, I'd have to think. Off the top of my head… Maybe I have a particularly rigid way of thinking, but my feeling is that it didn't change much, not really. What did change was my perception of them, the leaders and ideologues of the KGB. But that's a separate conversation.

The most interesting result of studying the archives is learning about their views on that very movement. The most interesting conclusion I drew for myself from these documents is that they never developed a systematic understanding of what the dissident movement was. Just as they didn’t understand what was happening when dissident activity suddenly and unexpectedly emerged in the Soviet Union, they continued not to understand later on. But that’s one side of the matter, one side of the coin. The other side is that they apparently understood perfectly well what threat the awakening of civic activity posed to them. There was a very interesting memo, actually two memos from Andropov to the Central Committee: one was, I believe, in December 1974, and the other was at the end of 1975, where, by all appearances, he was responding to some inquiry from the Central Committee. This was at a time when the efforts of Soviet leaders were aimed at achieving international détente; the Helsinki Accords were being prepared, and so on. And there was probably a question along the lines of: dear Yury Vladimirovich, aren’t you jailing too many dissidents? This is harming us in the international arena... The question was something like that. And in response, Andropov drafted a report in which he writes, somewhat resentfully, that actually we are not jailing very many at all, that under Khrushchev, during the so-called Khrushchev Thaw, far more people were jailed. And he confirms this with figures broken down by year. (That memo of his is perhaps the only source for the statistics of repressions during the Khrushchev era.) And indeed: it turns out that in, say, 1959 alone, almost two thousand people were imprisoned, as many as in ten Brezhnev years, from 1965 to 1974. That’s the first point of his response. And the second point is very interesting. I don't have the document in front of me, but I remember its essence very well. He writes: understand, we are jailing not too many and not too few, we are jailing exactly as many as are needed to keep the situation from getting out of control. That is Yury Andropov’s opinion. I think his idea of what it means for the “situation to get out of control” most likely formed in Budapest in 1956. This is a very curious perspective: political repression as a regulator of the regime's stability—that's how he understood the issue. Yury Vladimirovich was right: indeed, this regime turned out to be incompatible with public freedom, as perestroika clearly demonstrated. Well, besides that, the memo of course also contained all sorts of ideological incantations like “the remnants of the undefeated classes” and so on—but that's not interesting; that, it seems to me, was just obligatory rhetoric. The main thing is in that formula: “exactly as many as are needed to keep the situation from getting out of control.”

A. Roginsky, D. Raiko, Yu. Shmidt, A. Daniel, L. Bogoraz, V. Sazhin, S. Dedyulin, B. Mityashin. Leningrad, May–June 1976.

— To some extent, the dynamic of these repressions confirms the truth of his words. As the dissident movement was practically crushed by the mid-80s and this dynamic increased, the regime accordingly became much less stable and soon collapsed.

— Yes, yes, I completely agree with you: Yury Vladimirovich apparently failed to appreciate that side of the issue. It's no accident that perestroika began soon after the dissident movement was crushed—nature abhors a vacuum. I think that's how it is.

And it's also very interesting, since we're on the topic of arrest statistics for political articles: in the post-Khrushchev era, these statistics do indeed show a more or less steady decline by year. But with two noticeable spikes: a small peak in 1969 and a second peak, also not very large, in the early 1980s.

— A reaction to Czechoslovakia and Afghanistan?

— I think it was more a reaction to Czechoslovakia and Poland.

— Yes, of course, most likely. You agree, as I understand it, with the statement that by the mid-1980s the movement was effectively crushed. Isn't this connected to the fact that during perestroika dissidents played a relatively small role and only a handful of movement participants entered the state structures of the new Russia?

— I don't think that's the reason. The fact that dissidence was crushed is, in my view, a fact. At least, most of the structures and institutions created by the dissident activity of the old human rights type had indeed been destroyed by 1984. Both the Helsinki Group and the *Chronicle of Current Events*, and a whole range of other dissident institutions.

— The Solzhenitsyn Fund.

— And the Solzhenitsyn Fund, yes. That's true. But it seems to me that first of all, we need to understand why it was crushed. It's true that the scale of arrests began to increase slightly after 1979; there was that spike, which I see as the “Polish” spike, an echo of the events in Poland. But before that, an increase in pressure never led to the disappearance of the dissident movement! New people immediately came to replace those who were arrested, who stepped aside, or who emigrated. But from the early 1980s, new people more or less stopped appearing. Some did, but in much smaller numbers. The outflow began to exceed the inflow.

I think the main reason is this. When, in the second half of the 1960s, dissident circles and companies consolidated into a single community and the main voice of this community appeared—the human rights movement—it was a total novelty for the public. It was a conversation about things no one had ever spoken about before, and in a language no one had ever used before. And society very ardently and animatedly supported the dissidents. It was interesting and new, perceived as important. When [Alexander Yesenin-]Volpin led people to the square in 1965 under the slogan “Observe your own constitution!” it was something new and astonishing. Or take the *Chronicle*—I told you how painfully we felt, for example, the interruption in its work in 1973. But gradually, as the dissident enlightenment efforts succeeded, the preaching of legal values ceased to be perceived as a discovery and became a commonplace, a banality for the proclamation of which it was pointless to risk one’s well-being and freedom. Well, yes, we’ve already learned that obeying the law is good and not obeying it is bad; we’ve already understood that the authorities violate human rights with all their might, so what’s next? Here I am reading for the three-hundredth time in the *Chronicle* that such-and-such article of the Code of Criminal Procedure was violated at a certain trial. I already know that they violate all the articles and will continue to violate them—so why should I read and retype all this drivel, endangering myself and others in the process? I personally felt this very acutely in the last years of my work at the *Chronicle*. Yes, the size of the issues increased, the level of detail in describing events grew, the information coverage expanded—but this information was no longer, as they say, in public demand. People no longer wanted to learn what they already knew, nor to listen to appeals in defense of values they already shared. In a sense, the success of the dissidents’ preaching in society predetermined the exhaustion of human rights dissidence itself. The system of values that the human rights defenders advocated for became the latent value system of the social environment that supported them. And there was little direct practical benefit from the protest activity: the human rights defenders picked at the Soviet government in every way, but it couldn't have cared less! And the public demand for dissidence of this kind dropped sharply.

But during perestroika, the dissident legacy, the dissident perspective on social problems, turned out to be very much in demand! Compare Gorbachev's reform program with the program of change outlined, for example, in the 1970 appeal to Brezhnev from Sakharov, Turchin, and Medvedev—in essence, it’s the same program! Of course, I don't mean to say that Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev simply laid this 1970 reform program out in front of him and began to implement it. I suppose it was a bit different: simply that the intellectual leaders of the perestroika era—[Yuri] Afanasyev, [Yuri] Burtin, and other publicists who shaped public opinion—had been brought up on dissident samizdat. And throughout the second half of the 1980s, they broadcast dissident ideas to the general public. For example, the concept of human rights. At that time, it was not questioned by any social forces. Across the entire political spectrum, from the left to the far right, all anyone talked about was human rights.

— But why then did dissidents, people with a dissident past, not become active figures, not actively shape the new politics?

— Well, that's another story. To begin with, dissidence in the broad sense of the word has always existed. It existed in the fifties, and you can find manifestations of dissidence in the forties, and so on. But from the mid-1960s, a new phase of the Resistance began, and the most characteristic thing about this new phase was that it ceased to be political. It was anything you like—cultural, civic, moral, metaphysical—but not political. The rejection of political struggle was very strong, especially within the dissident milieu. I well remember a phrase my mother was fond of saying: politics is a plague-ridden sphere of human activity, and you mustn't go near it. And she was a very authoritative person in dissident circles. The dissident era was an epoch of very peculiar opposition movements: non-political and meta-historical, existential, not striving for a real goal, not interested in results, indifferent to victory. It was a kind of metaphysical and meta-historical activity. People sought support in law, in morality, in anything—but not in political pragmatism. And when independent political activity became possible in our country, other generations, other people got involved—and former Soviet dissidents were not inclined to get involved. Not because they weren't allowed. Of course, they were pushed out, too. The emerging post-Soviet elite was pushing out the dissidents, not allowing them to have a serious influence on politics. But they themselves weren't eager to join in, that's the thing.

— Here one can recall a striking exception to the rule—Academician Sakharov and Sergei Adamovich Kovalev, who, in fact, went into politics at Sakharov's insistence.

— Yes, Sakharov is an exception. But Sakharov was an exception in general. He contained dissidence within himself, but could not be contained by it. He had a very powerful mind. For him, politics was primarily an instrument for solving the global problems of humanity. He really did not shy away from politics, but his priorities were different; he lived on a different scale and with different time horizons. Universal disarmament, the gap between rich and poor countries, ecological threats to humanity—that was his scale. And when he turned to current political problems, to political logistics, he very often displayed an almost childlike naivety. Take his attitude toward national conflicts: he simply could not understand them because they are not of a rational nature, and his approaches to this problem are strikingly naive. Or his draft constitution: touching to the point of tears and, at the same time, completely unrealistic.

As for Sergei Adamovich, I would say that, from my point of view, Sergei Adamovich never really went into politics. While he had not yet become merely an opposition publicist, but was still a high-ranking government official, that is, from 1990 to 1996, he was doing the same thing he did in his dissident life—human rights. He was the chairman of the Supreme Soviet's Committee on Human Rights, he was the chairman of the Presidential Commission on Human Rights, he was Russia’s first ombudsman. These are points of contact with politics that are not yet quite politics—and in post-Soviet Russian reality turned out to be not politics at all, but the same old struggle with the regime. That's no accident. Can you imagine Sergei Adamovich, for example, as the minister of internal affairs (laughs)? He would not have taken that position.

— And perhaps it's sad that we can't imagine him as a minister?

— It is probably sad, but it was inevitable in the conditions of post-Soviet Russia. He would never have been allowed to have real power. He understood perfectly well that there is no politics without compromise, he was ready for compromise—but up to a certain point. They tried to use him as a decoration—and Kovalev did not want to and could not exist as a decoration. That's why his political career was short and ended in his resignation.

— Looking back, wasn't this disdain for politics a mistaken dissident strategy?

— You know, it was what it was. What do you mean by “mistaken”? It couldn't have been otherwise. The “anti-political” worldview of Russian dissidents (I emphasize, specifically Russian: in the Baltics, Georgia, Armenia, even in Ukraine, everything was slightly different) was the result of specific historical circumstances. After all, human rights dissidence was born among the humanitarian and scientific-technical intelligentsia, whose experience was shaped by the history of the 20th century. What politics did they know, what ideology? They had a sharp idiosyncrasy toward ideologies in general; they knew only one ideology—the one that had led a great country to a state of idiocy. They knew only one kind of politics—the kind that had led the world to the catastrophe of the Second World War. And the way out of the dead ends the country had reached, that the world had reached, they, it seems to me, were not prepared to seek in politics. For them, politics was something that decent people do not do. Whether it was a mistake or not, it was the outcome of their life experience. And they had no other experience. The same Sergei Adamovich has a number of very interesting articles on this topic; he also tried to square this circle after he was no longer an active… I won't say politician, I'll be more cautious—a statesman. He has a work titled *The Pragmatics of Political Idealism*, where he argues that the only correct, effective politics is idealistic politics. But there was no place for this idealistic politics in the new Russia. Nor is there a place for it in today’s world. Another question is that maybe it would have been the only salvation for the country and for the world, but neither the country nor the world was ready for political idealism. And the dissidents could not have been otherwise.

Of course, this statement of mine, like any general judgment, can be accompanied by a mass of counter-examples—both specific human fates and specific actions and deeds. But nevertheless, it seems to me that these counter-examples do not transform quantity into quality. The quality remains as I have described it.

— Whom would you name (besides Sakharov) as such a counter-example, an exception?

— Well, it was always thought in dissident circles that if we had someone who thought politically, it was Vladimir Bukovsky. Supposedly, he had political intentions, political motivations, and so on. In the perestroika and post-perestroika years, he partly confirmed this reputation of his with various political steps: for example, he ran for president two or three times, I don't remember now. But, in my opinion, these were also more symbolic gestures. Vladimir Konstantinovich viewed his candidacies, it seems to me… I mean, one would have to ask him, but it seems to me that he saw them as gestures nonetheless. Political, but gestures. And a gesture—that’s from dissident practice… Who else could I name as a counter-example? Well, perhaps Revolt Ivanovich Pimenov. But he died in 1990. And in general, Revolt was an atypical dissident. The late Kronid Lyubarsky had some elements of political thinking.

There is one person who came out of the dissident movement whom the general public considers successful in today's politics—but I don't think you'll like this example: it's Gleb Pavlovsky. But he’s not really a politician either, despite the rumors that he is a “kingmaker,” that he allegedly made Putin, and then served as his grey cardinal and so on. I think Gleb himself inspires three-quarters of these rumors. He's no politician, of course. True, he tries to be an ideologue—but that’s a completely different job. And he's a weak ideologue at that, an uninteresting one; his dissident texts were much more brilliant than his current ones.

In general, today’s politics—without the dissidents, their idealism, their metaphysics, even their rigorism—has become as shallow as a puddle. But that’s the point: the dissidents believed that politics is always like that and can't be otherwise. Do you remember Blok's statement about the Marquis’s Puddle? The Marquis’s Puddle of politics in the ocean of the human spirit, and when a storm brews in the ocean, some ripples start there too... Forgive me for quoting from memory. This formula of Blok's was always, to one degree or another, a part of the dissident consciousness, even if some of them didn't know it.

However, the real Marquis's Puddle is not a puddle at all, but a sea bay of sorts, albeit a shallow one. Kronstadt is located there, and there are storms there, and ships, it happens, sink. And still, it’s a shame: if you’re going to drown, it should be in the ocean, not in the Marquis’s Puddle. But that is exactly what is happening to all of us now.

=========

We thank Alexei Makarov of International Memorial for his help in fact-checking and selecting illustrations