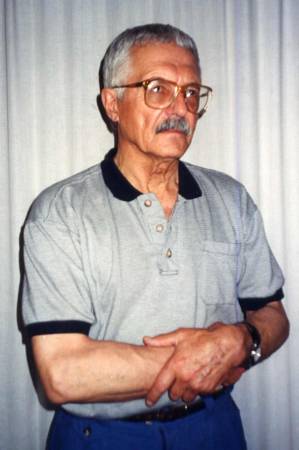

OPRYSHOK. An interview with Hryhoriy Andriyovych HERCHAK on June 12 and 16, 2003. Last reviewed - 09/27/2013.

Vasyl Ovsienko: On June 12, 2003, in the city of Kyiv, we are recording the story of Mr. Hryhoriy Herchak. Hryhoriy Andriyovych Herchak.

Hryhoriy Herchak: I was born on December 10, 1931, in Ternopil Oblast, Zalishchyky Raion, in the village of Solone, but we pronounced it with the stress on the letter “e”. My parents were poor. I don’t remember my father because, as my mother said, he had served in the Ukrainian Galician Army, and later the Poles wanted to arrest him, so he somehow made his way abroad through Czechoslovakia and ended up in Argentina, in Buenos Aires. After that, he returned in 1930 things had quieted down, and they had forgotten about that arrest, I suppose. I was born. I was about four years old when my father went back to Argentina to work.

V.O.: What was your father’s name?

H.H.: Andriy Herchak. My mother was Anna Herchak, maiden name Shevchuk.

V.O.: And how long did your mother live?

H.H.: My mother lived to be 52. She was partially paralyzed—the Muscovites beat her during an interrogation because of me, after I had joined the underground. She was bedridden for a long time and couldn’t walk.

We were poor. We mostly had a four-grade education, but my mother knew a little German because she had attended five grades in an Austrian school. She was such a patriot, a member of the “Prosvita” society she attended some homemaking courses and would take me, just a little boy, with her. She taught me to read before I even started school. At the time, a series of books for the patriotic upbringing of children was published, I believe, in Kraków by the “Svit Dytyny” (Child’s World) publishing house—she subscribed to them for me. In Zhovkva, there was a monastery that published a church magazine called “Misionar” (The Missionary). It contained educational, patriotic stories and articles. So she subscribed me to “Misionar” and “Dzinochok” (The Little Bell), and I read them and was raised that way. My mother was a member of the library at the reading hall. She kept a diary, not writing in it every day, but she did write.

V.O.: And which school did you attend?

H.H.: I started school under Polish rule. I went earlier than most. In school, there was the Polish language and the Ruthenian language, meaning Ukrainian. And when the Soviets came in 1939, I was supposed to start second grade. Just then, cavalry came breaking through the border. There was this teacher, Tsviakhova, a Ukrainian, despite her name. It turns out she was a Ukrainian patriot, but she didn’t yet know what the Soviets were, whereas most of our people did. When the Red Army was “liberating” us from the Polish yoke, she called out, “Children, everyone!...” A paved road—a highway, or as we called it, a *hostynets*—ran past our village. And we all lined up there. A commander rides up on a dark bay horse, with a star on his cap. Many of them spoke Ukrainian—we weren’t far from the Zbruch River, about forty kilometers. They stopped and greeted us. And the teacher said, “Children, the Red Army has come to us! Rejoice—Ukraine is free! Clap your hands!” But I already knew there had been a famine in Ukraine because people would visit my mother and tell stories about it. Most people didn’t know that, though, and some perceived this as a liberation.

The commander dismounted his bay horse and presented Mrs. Tsviakhova with a red star, pinning it to her chest. He greeted the children, and they rode on. A few days later, Tsviakhova was gone. When the arrests began, they arrested her too, because they were arresting the intelligentsia. Maybe it wasn’t a few days, but a few weeks later. First, they arrested all the intelligentsia, and then more and more people. They even arrested the head of the Ukrainian reading hall, a relative of ours. Because Poles also lived among us. In Ternopil Oblast, over forty percent of the population was Polish. Along the Zbruch River, there were special settlements from the *komasacja* [land consolidation]. They were like farms: a house with a field around it. For Ukrainians, the fields were scattered in little patches, like carpets. But the Poles had farms like in the West. The Polish state, which emerged after the First World War, gave land to those who had fought for a free Poland. Later, I read the memoirs of an officer, Cebulski, called *Czerwone noce* (Red Nights). He writes about how the Poles fought against the Banderites even under the Germans. Because the Germans fought against the Poles, against the Banderites, and against the Soviet partisans in Volyn. He writes very interestingly—do you understand Polish?

V.O.: I can read a little.

H.H.: I’ll write it down for you—*Czerwone noce*. The provocations they staged! They would dress up as partisans with tridents and shoot at Germans, and in retaliation, the Germans would burn down Ukrainian villages. He writes this himself Poles specifically gave me that book here in Kyiv after I was released. It has a very interesting foreword about how they settled the area from the Zbruch with these military colonists. They had a lot of weapons. They had the “Strzelcy” (Riflemen), similar to our “Sich” and “Plast” societies. But we weren’t allowed to have weapons, while the Poles had small-caliber rifles, called Flauberts. And we had “Plast” to defend ourselves from the Red invasion.

That was the problem when I was born. Forty-three percent of the population in our oblast was Polish, and fifty-seven percent in Lviv Oblast. I read that in a Soviet encyclopedia, by the way. So there would have been big problems if what happened hadnt happened.

V.O.: These arrests of the Ukrainian intelligentsia—did they happen as early as September?

H.H.: Those were the first, main arrests, but after that, they continued constantly the NKVD took more and more people, I remember.

V.O.: There’s a man named Vasyl Pirus, who also served 25 years…

H.H.: I know him.

V.O.: He lives in Kherson Oblast now I visited him. He says that Hitler saved Western Ukraine. Because, he says, if the Bolsheviks had run things for another couple of years, there would have been no one left, no OUN, no UPA could have emerged, because they would have arrested and exterminated everyone.

H.H.: They already knew someone was informing on us. There was the KPZU—the Communist Party of Western Ukraine—so of course, there were informants there… Later, people became disillusioned with the KPZU. There were some who joined the KPZU, saw what it was, got disillusioned, and switched to the OUN. Shumuk wasn’t the only one like that. (Shumuk, Danylo Lavrentiyovych, b. 1914. As a member of the KPZU, he spent 5 years in Polish prisons. The “liberators” did not trust him and mobilized him into a penal battalion. Unarmed, he was captured by the Germans, escaped, and joined the UPA. In 1944, he was sentenced to death released in 1969. Imprisoned again from 1972-1988. In total, 42 years, 6 months, and 7 days of captivity, including 5 years of exile. Member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. Lived in Canada, and from 2002, in the Donetsk region with his daughter. Died on May 21, 2004, in Krasnoarmiisk. - V.O.).

I was in school, and when the Soviets came, they considered the Polish school to be weaker, so they put us back in the first grade of the Soviet school.

V.O.: And that teacher, Tsviakhova, was she gone by then?

H.H.: The teacher who said we were free was already gone. With her red star, poor woman… She was a good woman, a young widow. I don’t know where she ended up, poor thing. That’s what happened. I started going to a Soviet school. I remember, in the classroom, there was a portrait of Stalin. And one of the boys shot a wad of paper at Stalin with a slingshot. The teacher came in. My God, he ran off, and they took all those students away. The teachers knew who did it, but they kept quiet. They hung up a new portrait. People didn’t yet realize what a strict government had arrived.

And then the second liberators came. Many people welcomed them.

V.O.: That’s interesting, how were the Germans received?

H.H.: Well at first. They declared an independent Ukraine in Lviv. A biplane used to fly to Chernivtsi (and Chernivtsi is close to us, about 40 kilometers away), and it had blue and yellow stripes on its wings. I was so happy… All this lasted for about two months, and then they arrested everyone.

V.O.: Those the Soviets didn’t arrest, the Germans took away.

H.H.: They started with the government, but then they kept taking people. There was a Ukrainian police force, but then it turned against the Germans. The UPA was created—and that police force fled to the UPA with their weapons. In our area, there was only the underground, but then some UPA units appeared here too. There was also trouble with the Poles, all sorts of provocations the Germans even burned down part of the village. The Germans did everything very cruelly, it was terrifying. The Russians had a good network of agents here, and they first took the activists, and then others. But the Germans would either shoot every tenth person or do something similar.

V.O.: They didn’t have enough information, so they just did a “cleansing.”

H.H.: We children were terrified when the Germans came on their raids. These Germans with Gestapo plates on their chests—about ten motorcycles with sidecars, MG machine guns. And we’d be grazing cows by the road. The older boys would be with us. We’d lie down because we were afraid of them, but the older ones would say, “Don’t lie down, or they’ll think… Act like you’re not afraid.” We were so scared of those Germans!

Then they created the SS Division “Galicia.” The Banderites were against the “Galicia” division, but two of my relatives joined it for some reason. One was my uncle Mykhailo Shevchuk, and the other was my uncle’s eldest son, also a Shevchuk, but I don’t know his first name. And this uncle was a good blacksmith. He joined the division, and then, when it was all over, he studied somewhere in Germany. For some reason, they were traveling to Chernivtsi, and two of them went on leave. The Banderites didn’t shoot those who came on leave, but they did disarm them. My uncle was walking from the city with his carbine, and they disarmed him all he had left was his gas mask. So he came to the village but didn’t sleep at home, so the Banderites wouldn’t beat him up. I remember my uncle telling me he was disillusioned: the Germans wanted to send them on punitive expeditions against Polish partisans, but the division didnt want to go. I heard that as a young boy. My uncle disappeared without a trace somewhere.

V.O.: An uncle—that’s your mother’s brother?

H.H.: Yes, on my mother’s side.

V.O.: And on your father’s side, it’s a *stryi*?

H.H.: A *stryiko*, yes. When the second Soviet liberators came, the liberation movement was already strong. We lived in an area with few forests, just small woods, but even we had small partisan groups. That’s when the trouble started, because the NKVD followed right behind the front lines. They had some information. There was a mobilization for the front. They gave you little training, just here and there, and then to the front lines, especially Ukrainians. Later, in the camps, they told me there was an order: train Ukrainians lightly and send them “forward” against German pillboxes—as cannon fodder. My uncle Vasyl Shevchuk and my uncle’s son didn’t want to join the Soviet Army and went to the UPA—they packed some salo, onions, and dried bread and went to the Tsyhanskyi Forest, where the forests were bigger, north of us. They were supposed to gather there. Those boys were walking, and Vasyl Shevchuk said to my mother, “Auntie (we didnt say ‘tiotko’), I’m saying goodbye!” He kissed her and said, “I’m gone, I’m no longer here!” He said that and left, poor man, but the NKVD were already waiting for them there. On the road, where they had their meeting point, about a third of them were killed, because someone had informed on them. So very few made it to the UPA, but Vasylko managed to escape. He threw away his weapon and joined the Soviet Army, but he died there too.

After that, the front moved on, but a fierce struggle continued here the UPA was large by then.

V.O.: When did the front pass through your area?

H.H.: It passed in the spring of ‘44. The Germans were surrounded in our area they were breaking through towards the Dniester, and then there were paratroop landings, fighting was going on, and the front stopped there on the hills. We were evacuated to another village, but that’s a long story… And all those arrests—it was a complete nightmare. I remember, as soon as the front passed, those rear-echelon troops came through, and some Ukrainian officer (they had shoulder boards the second time they came, the first time they didnt), probably a captain or a major, could speak Ukrainian. It was the first time my mother saw those arrests. She was a member of “Prosvita,” so she had a small certificate under glass, with something written on it, angels holding a book, painted in yellow and blue colors. It hung on the wall, showing she was awarded it as a member of “Prosvita.” He looked at it for a long time, then said to my mother, “Take this down and hide it, burn it, or you’ll be in trouble for it!” But she didn’t know this—a trident is hanging in the house, so what? We were starting to understand the Soviet regime.

We had a big problem with the UPA partisans—war, arrests, burnings, NKVD everywhere. And then the Poles—they were militarized. When the Polish Army retreated in 1939 toward the Romanian border—the Romanian border on the Dniester was 20 or 25 kilometers from us, because Bukovyna was not yet part of Ukraine—they left weapons in those Polish colonies, stockpiled them, hoping for an uprising. All the Poles were militarized because these were colonists who were former soldiers. The youth were in a sports-military society, “Strzelcy” (Riflemen), where they were taught to shoot. We had “Luh” and “Plast,” but we weren’t allowed uniforms it was just a sports society. We did exercises with sticks there, boys and girls. This was in every village. There were sports teams, volleyball, football. So when the Soviets came the second time, the Poles came out of their underground. They were even allowed to have weapons, and they walked around in *rogatywkas*—caps with four corners. The Soviets weren’t stupid—the NKVD thought: let them fight among themselves. In the villages, the Poles went with the Soviets against the UPA those extermination battalions were mostly made up of Poles. The Soviets werent stupid: let them fight among themselves. The Germans did the same thing. The Poles and Ukrainians couldn’t come to an agreement, because it was clear that they had settled and taken our lands.

And all of us young boys were ready to fight, gathering and hiding weapons, explosives after the war, burying carbines somewhere, filling hollows in willow trees with those German grenades. We learned all about those grenades with long handles. I came from a family of craftsmen—one uncle was a blacksmith, the other a carpenter and a locksmith, and I had a knack for it, so we stockpiled all that.

One day, a neighbor and I were standing around, it was drizzling, and there was a raid on the village. But we didn’t know about the raid. We were sitting by a split willow tree with a semi-hollow trunk, trading ammunition, cartridges. And suddenly, three Polish militiamen in *rogatywkas* walk up. I immediately threw everything into the hollow. It was a Sunday, I remember. And one of them asks, “What are you whispering about?” He asks in Ukrainian, because many Poles knew Ukrainian, having served in Ukraine. “Nothing,” I say. They just stood there. If he had looked into that hollow, he would have found everything. It was morning, and I was wearing an embroidered shirt. He looked at me and slapped me in the face, and I didn’t know what to say. One of my grandmothers had married a Pole—Wawro Potapiński. So I say, “Why are you hitting me, I’m one of the Poles!” They had three sons and a daughter. The daughter wore an embroidered shirt, but all the sons were like Poles. And the family held together like that. It happened often, because Poles had lived here for hundreds of years. Wawro’s sons were also in the “yastrebky” [extermination battalions]. He asks me, “What’s your last name?” “Herchak.” It didnt sound Ukrainian. “And where is your mother?” We went to my mother. It was Sunday, and my mother treated them to varenyky. He apologized to me, and that’s how we got out of it.

That’s the kind of trouble we had. And after that, the Poles were deported there was a bit of fighting, Polish civilians suffered, and so did our civilians. That whole slaughter… I don’t like it, but that’s how it was. This was in ‘45, ‘46.

V.O.: How were those clashes justified? What did people say about them?

H.H.: I can tell you this. The Poles were in the extermination battalions, so they gave the Ukrainians a lot of grief. And before that, some Poles sided with the Germans they specifically joined the German police and other agencies to fight against Ukrainians. And the Ukrainians were very nationally conscious, so the Germans persecuted them.

We had an incident. A man named Skalatskyi was traveling—I don’t know what his role in the OUN was—to the town of Tovste, near our village. A lot of Poles and Jews lived there. In our village, about 25% of the population was Polish there was a Polish Catholic church. But there were villages where they were more than half, even purely Polish villages—like Chervonyi Obrut. So, I want to tell you about that Skalatskyi. He was on his way to a contact point he had two guards with carbines. He was a civilian but was educated in some way. They are writing about him now—they say they found him in the archives. And they set up an ambush for him. We thought it was the Germans, but it was the Poles who did it—they found out he was going somewhere to the village of Sadky or the town of Grzybowice. We have a large burial mound there, about four hundred meters above sea level—this is already the Precarpathian region, the hills there are quite high, a couple of hundred meters. They were traveling on a sleigh, trying to escape. They killed one of them about a hundred meters away. The Germans took the bodies, and the others escaped.

The next day, my friends and I went there to see. We saw where the ambush was set up near the mound—the Poles had spread straw for themselves because it was cold to lie on the ground. We followed the tracks of those who fled. An expanding bullet had hit one of them in the head—the body was taken, but the top part of the skull with reddish hair was left behind, one of ours. We even found a few shell casings from Polish weapons. But we thought it was the Germans. It later turned out that the Poles had set up the ambush, and the Germans only collected the bodies.

They gave us so much grief that it led to that slaughter. The Poles then organized such outposts in the villages. A few kilometers from us were the Turkish fortresses—Khotyn, Kamianets-Podilskyi. The Turks had a line there. These huge fortresses, with dungeons underground, and on top, the Dzhuryn River flows. It’s a small river, with a waterfall where it descended into the valley. The village was named Chervone (Red) because on one side there was a horseshoe-shaped forest in the valley, and on the other, red granite cliffs. On that waterfall, there was a power station even back in Polish times. Electricity ran through our village the center of the village was electrified, the reading hall was electrified. In that village, back in the Middle Ages, after the Turks were driven out, there was a Polish monastery, some Kapitan Czerwenskego Grodu, everything there was built of stone, a *klasztor*, as they called it. The village was small, Polish, rich, located in a valley. It was almost a resort. I don’t know how many houses were there—maybe a few hundred. But the buildings were large, so Poles from other villages fled there, brought their weapons, and the NKVD armed them even more. They fenced the top with barbed wire, and there were posts below to keep anyone out. And if they had just stayed there, it wouldnt have been so bad. But what did they do? They needed to eat, and although they had some food, they needed more and more. And they needed to drink—so they would ride through the villages on sleighs, on horseback, taking pigs, calves, slaughtering them, not eating, but gorging. The place was full of them, because so many had gathered there. But the Soviets were not stupid either—they stationed a garrison of thirty men there, with a female doctor and a radio station, and they lived separately in those fortresses. To see what the Poles were up to, you have to have your own agents. But they turned a blind eye to the looting, or maybe they got a cut from it. It was that kind of time. People complained, but we didn’t have enough insurgents to defeat such a force—there were many military men among the Poles. And the district center was not that far—about 4 km to our village, about 8 to the district center. Because the district center then wasn’t Zalishchyky. They made the districts denser to have more garrisons, to make it easier to cast a net—to go on raids.

V.O.: What was the district center then?

H.H.: The town of Tovste, in Polish, *miasto Tłuste*. There were very many Jews and Poles there. True, after the Germans, there were almost no Jews left. So, people complained and complained. Finally, some units came from the Precarpathian region. When I was already in the camp, I met a man who took part in that battle. I didn’t want to ask too many questions, and he didn’t really want to talk about how it was, because, you know, maybe he had his case closed in a way that he didn’t have to admit his participation in that battle.

V.O.: So there was a battle for that village?

H.H.: Chervone, or as the Poles called it, Czerwonogród. It was the winter of 1945-46. The war was already over. I remember it was at night. We were ice-skating and on *narty*—that’s what we call skis. So, our small units, together with those who came from the Carpathians, surrounded them one night. They were in white camouflage, they even had a few mortars, because I myself heard mortars firing—whether from the Polish side or ours, I dont know, but people said the insurgents had a few mortars. I asked that man in the camp, “How did you get in—it was fenced off, wasn’t it? You have to go down, and there were posts up top.” It turns out, on the mountain slopes, water had carved out ravines. They were covered with snow. That night there was fog, a drizzle. One group—about 10-15 men—dressed in Polish clothes. They knew Polish (many of our boys knew Polish back then). They crawled under the wires where they could get through—I dont know if there was an alarm system or not—they got into the village and walked around in Polish clothes, with submachine guns. And when a flare was fired from outside—the signal to start the battle—the Poles went into combat, and those inside started shooting from within. A terrible panic broke out. The Poles thought there were who knows how many partisans there. The Chekists—there were about 30 or 31 of them—immediately broke through to the forest they managed to escape. Of course, they had a radio station, and the shooting could be heard in the district center.

This happened in the evening. We were still skiing near the highway. We saw some men in white camouflage arrive on sleighs and take positions in ruined houses (the people had been deported to Siberia). Some were digging holes in the snow and laying mines under the road. This was to stop any help that might come after hearing the shooting (it was about 8-10 km away), or after learning about it from the radio station. We didnt know who they were, but we were street-smart boys, we knew our weapons—so we figured they were ours. Then they came up to us: “Home, everyone go home immediately!” But we didnt run home we hid behind a fence and watched what was happening. They covered the mines with snow and took cover behind the ruined walls.

When the battle started, my mother and I were sitting by the window, with the lights off. The sky was red. We could hear mortar fire. It was terrifying. And a fire. No one went to help—let them fight among themselves! A lot of Polish civilians died there. We went there about five days later, and there were bullet-riddled featherbeds, pillows, blood on the walls. The bodies had already been removed.

That was some battle. It was around 1946-47, in the winter. I was studying in a Soviet school then. I lost another grade during the war. Under the German authorities, I think I only finished one grade. Under the second Soviet rule, I went into the third grade, then the fourth, and then I quit school and grazed cows. I grazed the neighbors’ cows for seven years, helping my mom a little, because life was very hard. They didn’t start collective farms in our area because the insurgents wouldn’t allow it—if you joined a collective farm, they’d bash your head in, and sometimes they even hanged people, if they were informers and snitches. They were strict about that, because insurgent revolutionary movements were always strict. There were village council heads who were given weapons, and they often paid with their lives for it, because the Banderite underground security service would get them.

OPRYSHKY

We strongly supported that movement and resistance, because I had already read all sorts of patriotic books about the Cossack era, about the Ukrainian Galician Army, about Petliura’s army, I had read about Makhno. And what spurred us to resist even more was the fact that in our region, in the Carpathians, there had always been *opryshky* and rebels. The last one in our area, even under Poland before the war, was a man named Lubynetskyi. Legends and rumors circulated about him. My grandmother was taking a goat to sell—under Poland, you had to pay a tax on goats and sheep. The path from the village went through the forest. And he asks her, “Grandma, how are things in the village? Where are you taking the goat?” “Well, I want to sell it, because I have no money to pay the taxes.” “Sell the goat, and buy yourself a cow.” “But with what?” “Here’s some money for you.” My grandmother used to sing ballads about the *opryshky*, about Dovbush: *“Oy po hayu zelenenkim khodyt Dovbush molodenkyi, na nizhku nalyahaye, na topir si pidpyraye.”* [“Oh, through the green grove walks young Dovbush, he limps on one leg, leaning on his axe.”] And I would listen and think that one day I would also be…

V.O.: An *opryshok*?

H.H.: Yes, yes. By the way, one of my uncles, Ivan Hirchak, was a rebel he used to set fire to Poles’ property because they had taken our land. They gave us the worst land, and the Polish lords took the best. So that rebellion was a natural consequence. Some *ksenzhna*, a princess, would arrive, already on crutches. I had the heart of an *opryshok*, and I would watch her arrive. She didn’t live among us, but somewhere else, and her lands were managed not even by Poles, but by Jews, because the Poles were off somewhere in Paris that Polish gentry was lazy… A large orchard, fields stretching toward the Dniester—it was all Polish. The orchards here are good, the climate in the valley is very good here, by the Dniester, cherries ripen as early as May. There’s sun, a microclimate. All the Poles knew that Zalishchyky was where the cherries and tomatoes came from, that’s what Warsaw ate. You could trade here, people made a living from it. I watch her get out on crutches, with her security, and go to the *soltys* (like the head of the village council), and the people worked like semi-slaves—they were called *fornali*—on the *filvarok* for that lord. A latifundia, a *legenshaft*, a *folwark* in Polish. It was terrible—the little houses were like barracks, and the land for gardens was divided into tiny, tiny plots. People worked there for half the price. That’s why many of the *fornali* went over to the communists. When the first Soviets came—I’m going back again—these *fornali* pinned red stars on themselves. And I sympathize with them—what did they know, poor and uneducated? The liberators came: the land is yours. That happened.

I remember it like it was yesterday, there was a Jew named Chmelyk in our village. We had about four Jewish families in our village, very poor Jews. We got along well with them, (unintelligible short, rapid phrase), we went to school with them. We called them “zhydy.” Today, it sounds like an insult. I can tell you how Jews in Canada view the term “yevrey.” A Jew named Joseph Stukler served in the UPA. They told me, “You should go and meet him.” Because I had connections with the underground. He had been in some German camp, the prisoners were about to be shot, but a UPA unit raided the camp. There was a small group of Jews there, about ten men. The elderly ones were let go, and the rest were told that anyone who wanted to join the UPA could. So Stukler joined the UPA because he was a doctor, I think, from Warsaw. I met him in Toronto. When a new émigré from Lviv was introducing me to him, I walked over thinking, how should I say it—*zhyd* or *yevrey*? Because for me, the word *zhyd* was already associated with Russian hatred, so I called him a *yevrey*: “I was imprisoned with *yevreyim*.” He really laid into me: “I am not a *yevrey*! That’s what Russians call us—I’m a *zhyd*! You remember that!” “I’m sorry,” I said, “I thought I would offend you if I said that.” He served as a doctor in the UPA, told me many stories, but thats another topic.

So, this poor Jew Chmelyk, how did he make a living? He was a rag-and-bone man—you wouldnt remember that…

V.O.: I remember—after the war we also had “onushnyky,” who collected “onuchi”—rags, that is.

H.H.: He would ride around, one miserable horse, a cart… We call that useless junk *katran*. “Housewives-s-s, rags, give me your ra-a-ags!” He would ride and ride, people would bring things out, and he would give them some matches, this and that. And the poor man made a living from it. Clearly, life was hard.

V.O.: They also brought needles, pins. And clay whistle-roosters.

V.O.: Yes, they brought things for the children too. That Chmelyk, when the Soviet government came, he pinned on a star—and now he was a “Soviet man.” In that *folwark*, in that Polish latifundia, there was a large garrison of NKVD soldiers. We children loved to watch what kind of soldiers had come to us, to look at their weapons. It was a Saturday, I remember, and one Jewish butcher and this Chmelyk, the one who traded in rags, were slaughtering cows for the garrison’s meat. Or maybe they were heifers, I don’t remember anymore. Dogs were running around… In our village, the Jews were very religious. And the elders said, “Chmelyk, what are you doing—it’s the Sabbath today?” “I sold my Sabbath for five kopecks,” he said in Russian, I remember.

V.O.: Because he had become a communist?

H.H.: He was a communist. And the communists also arrested rich Jews—the Zionists, the Jewish patriots. That’s why they started helping the insurgents, the UPA.

When there were raids, the insurgents would send us: go! Because children could get through. “Count how many of them there are, how many weapons, and listen to where they’re going—maybe you’ll overhear something.” We would go, getting used to that kind of reconnaissance. I want to emphasize, even now I can’t believe how patriotic people were, how honest. We would drive the cows out to pasture behind the village, and the boys would say, “The partisans are quartering at my place.” And he’d say for how many days. And as we drove the cattle from the pasture, we’d glance at those yards: the sun is shining, the partisans are stripped to the waist. We drive the cattle home for lunch—they’ve already slept and are cleaning their weapons, their machine guns. Does that mean they trusted people? We live near the town, near a railway station, and all the stations are guarded by garrisons—you could just go and report them… The patriotism was that strong! Looking at the population today, I can hardly believe it. It was so easy to wage a struggle with the support of the population that’s what our people were like.

V.O.: Practically the entire population supported the UPA.

H.H.: It seems so. It was only later, when the population broke down, in the fifties, heading into the sixties, that things changed. They used to drill us, the young ones—the older people had separate lectures from Banderite instructors.

I have to digress again… There was a garrison at the railway station. It guarded military depots, explosives there were also German weapons in those buildings. And the head of security was from Kyiv, a Ukrainian, I think a senior lieutenant or a captain, no higher, a slender young man, [unintelligible] after the war ended. By then, almost all the Poles had been deported from those homesteads, and Lemkos from Poland were settled there instead. One Lemko man had four daughters. Because Lemkos had many children—eight, ten, they had large families, but in Galicia, not anymore—one, two, three, some had four. My uncle, the one from the division, had four. Not far from the railway station, Lemkos lived in little houses near a small forest, near the former lord’s orchard. That officer used to visit the Lemkos and fell in love with a Lemko girl. And these Lemkos had contact with the insurgents because they lived near the forest. So he would come during the day, and at night the insurgents would come—for reconnaissance, for a bite to eat, to have their laundry done. And one day they said about the officer, “He’s a good man.” And the officer knew Ukrainian he was from Kyiv. The partisans decided to get to know him. They disguised themselves as border guards. We had border guards because the Romanian border was 60 km away—the border control zone was 60 km. With them was a man named Solovey, also an officer, from Eastern Ukraine, who had defected from the Red Army to the underground. He knew how to act, he knew Russian. So, they put on border guard uniforms, and they all kept quiet while Solovey did the talking. The officer came to the Lemkos’ house, set down his submachine gun, his pistol still on him, and sat at the table while they served him. And the partisans came out of the woods: “Hello, who are you? Your documents? Hands up!” He shows his documents. They take his submachine gun, his pistol too: “Come with us!” They took him into the forest and talked with him. They gave him literature. And he defected—it’s unbelievable!—to the underground after the war. And it later turned out that someone in his family had been arrested. If I knew his last name, I would gladly tell his story, because he later became my instructor. The security service vetted him—how they did it, I don’t know, but he was trusted and died a very heroic death. They gave him the pseudonym Novy (New), and later, when I was in the underground, I took his pseudonym. He shot himself when he was wounded—a very heroic death.

They gave us lectures—separately for the young ones and separately for the older ones. They would cover the windows, post guards, and give a lecture. This was once a week—lectures on the history of Ukraine. They gave us literature. The educational work was very good. They told us, I remember it like it was yesterday, about the famine in Ukraine—and we had already heard about the famine. They said that some 4-5 million had died. To be honest, I thought they were exaggerating to make us have a greater hatred for the Muscovites, for the Soviets. When they talked about the Kremlin, about Stalin, about the debauchery, the cruelty, that you could walk into a cabinet and never walk out, I didn’t believe it, we didn’t believe it—I thought it was an exaggeration to make us have greater hatred. But when I ended up in Vorkuta in 1954, in the North, in a camp, and we were sitting on the bunks during a huge blizzard, there were also “real communists” there, Kremlin workers, who told stories—and I, just a young boy, listened and thought: My God, the Banderites back then didnt even know about these crimes—these were colossal crimes! And we didn’t believe it…

I can also tell you how they raised us. This was already the beginning of 1947. I loved to sing, and everyone in our village loved to sing. And I sang pretty well. The older people would gather to sing carols, and the children would sing shchedrivky—we have very rich Christmas traditions, very picturesque—all mixed up with pagan times. We would gather, those who sang well, into groups and go around. But after the war, the Soviets allowed it—brew moonshine, and no one would touch you. Many people had permanent moonshine stills. And people began to learn to drink from the Russians. Because under Poland, we drank from tiny little glasses. They could make half a liter last half a day. True, under Poland, there was a temperance society, run by the nationalists. Members of the society didn’t drink or smoke at all. [End of track]. The boys were being prepared for the struggle. But here, drunkenness began to take root—and it takes root quickly.

V.O.: Yes, yes, Vasyl Dolishniy from the Ivano-Frankivsk region used to sing a *kolomyika* in Mordovia: “Thank God, thank God, the Soviets have come: now our eyes will be bleary from vodka.”

H.H.: This *kolomyika* says it all. Christmas. We prepared and went to sing *shchedrivky*. The whole village is singing. And everyone treats you to vodka. I’m returning home, I open the door to the entryway—and I smell a strange scent. You know, you can smell that military scent from soldiers. Not of *makhorka* tobacco, because in the UPA you could smoke by then, some did, but all the young guys didnt. Later, when I was with the UPA men, none of us smoked, only one old man, Dnipro—he smoked in the forest. It wasn’t allowed. And I didn’t smoke or drink. I started doing sports. Although my mother was a smoker and didn’t forbid me from smoking. Under Poland, she made a living by growing tobacco—and under Poland, not just anyone could grow tobacco, because tobacco was a “monopoly.” My mother was a specialist, she took a course, grew that wretched tobacco (and we had little land), knew how to dry it, packed it in boxes, into those bunches. Not far away, about 10 kilometers, there was a tobacco factory. She lived off that, she had a metal plaque: “Anna Herczak, plantator tytoniu” (Anna Herchak, Tobacco Planter). So she learned how, they buried all sorts of [unintelligible] in the ground, she dried it, smoked it, and guests would come to her for it.

But I want to talk about something else. Opening the entryway door, I smell that someone is in the house. I open the door—and there are four or five of them sitting there, the windows are covered, my mother is treating them to something, and they are waiting for me. And its already after midnight. My instructor, Novy—remember, that insurgent from Eastern Ukraine—comes up to me: “Well now, my dear boy, take a breath.” I blew. He hugged me: “My God, what a boy, not a has touched his lips. Even if you had drunk a little, I would have…” And he started kissing me. But my mother says: “Don’t praise him so much, he doesn’t want to go to church, he’s always messing with those bullets, he has some grenades, and once I found cartridges in his pocket.” “Don’t keep them like that. It’s good, it’s good, but hide them.” My mother: “What are you teaching him?” That’s how strict the discipline was, that’s how they raised us. So, I was raised like that and got raised all the way to the camps. (Laughs).

I must say that before this, I had a scandal with the Ukrainian insurgents. A lot of people were being arrested, deported to Siberia. They were already starting to resettle Lemkos in our area. This was around 1946, probably at the end of the year. We created a group and called it the “Opryshky.” It wasnt an organization. I was involved, along with Pavlo Bezvushko from our village and others. We sought revenge. We were like folk avengers. Some did more, some did less… If the village council head fined a woman for carrying firewood from the forest or for something else—we would either break his windows at night or hit him over the head from behind. He’s still alive. Sometimes we’d leave a note: “The Opryshky.” We would sign that we were the *opryshky*. There were some who mistreated people. Those foresters. To stop people from taking wood from the forest… Once, we stole a large boar, quartered it, and gave it to poor old women. We wrote: “The Opryshky.” Then we stopped, because rumors started spreading that there were such avengers and that they were being directed by older people. But that wasnt true.

One was studying at the university they called him Lemko. Maybe he was from the Lemko region. He had a certain accent. He was in one of the senior years. They came and arrested him. The police arrested him, because it was often the police, not the NKVD, who came to make arrests. They put him in an open truck and drove him away. And when the truck stopped at a red light in Chernivtsi, he jumped off, and the guards couldn’t shoot because there were too many people. He knew the area well and escaped. Sometime later, he came home and saw—it was winter then—an empty, desolate house, windows and doors broken, snow blown into the entryway, his relatives deported. A while later—his friends told me this later—word came that his sister and grandmother had died on the way in those freight cars. And he dedicated himself—so they said—to fighting them to the death, to taking revenge. He may have been the one leading these *opryshky*.

Some *opryshky* didn’t even know each other. I know that a man named Yosyp Hevchuk worked with us he was also arrested later. He only worked with me he didn’t know that I also worked with others. One time, they decided to blow up an NKVD or Red Army club. After the war, there were such clubs. I don’t know in which small town it was. And I was involved with weapons, stockpiling them, shooting in the fields.

Since I mentioned shooting, I’ll tell you that we set up a firing range for ourselves in the valley. And since gunshots can be heard from far away in the forest, we knew how to escape. For example, we found a Degtyaryov machine gun—it needed to be tested there was plenty of ammunition. We’d set up a newspaper about 100 meters away, draw a circle on it, and aim—doo-doo-doo-doo. And the shots could be heard far away. We’d practice for a bit in some ravine—and then quickly flee, so the Bolsheviks wouldn’t come. It wasn’t far from the town. About two kilometers from our village, about four from the town.

Once we were testing a submachine gun. A good submachine gun, I cleaned it, hid it, everything was quiet. In the village, some supply men were quartered—these were armed underground members who didn’t go on actions or contact missions, but just organized logistical things—food, clothing. By the way, the UPA was short on bandages—they called them *bandazhi*. If you bought too many of them in our area, it would immediately raise a signal. They would either start watching you or arrest you. It didnt matter who bought them—a woman, a child… I’ll digress again—I’ll be digressing until the end—they would send us to buy them at the Zhmerynka station near Vinnytsia, a major railway hub. There, in Vinnytsia, someone would get medical supplies from a hospital or a warehouse. So they would send us, little boys and a couple of girls, to bring them back. And one or two older women would go with us. We would get off in Zhmerynka, someone would meet us, pack everything for us, to make it look like we had been shopping. On the way there, they taught us: don’t say “pane” [sir], don’t say “Slava Isusu Khrystu” [Glory to Jesus Christ], but “dobryi den” [good day], so as not to arouse suspicion. I made several such trips. The rest we made from rags. We made cloth not from flax, but from hemp. We had more hemp. In the north, they sowed flax… Old clothing is soft. They would boil it—even my mother boiled it, and my aunt, in these big pots, in cauldrons. They would cover it, and it would simmer for a long time. Then they would iron it with a hot iron, and gently roll it up, after washing their hands. That’s how they made bandages. It was a tragedy. And the Chekists said that planes were dropping medical supplies and weapons to the Banderites. So I collaborated with the Banderites in this.

Besides the supply men, there were boys in the village who were on duty, helping the partisans, carrying out some tasks. They didnt have such strong connections or a command structure, so they were called by the slightly contemptuous term *okolotnyky*. An *okolot* is a threshed sheaf of straw. So these were the ones who hide in the straw, in the *okoloty*. They were a bit chubby, not tanned. Because those in the forest were so worn out, exhausted, tanned by the wind, because they had to walk and carry everything. But these guys got varenyky, and they liked to go and hang out with the girls. They didnt drink, though—maybe secretly, I dont know about that, I never heard.

When we tested that submachine gun, two *okolotnyky* were quartered at the edge of the village, not far from our “firing range.” It was just before evening. There was a wedding, one of them changed into civilian clothes and went to dance with the girls. The other had an illness—scabies. So he was soaking in some herbal brew in a tub, treating the scabies, in a barn. And suddenly, there’s shooting. He has to change out of his wedding clothes and tremble, thinking there’s a raid or something. Then someone informed on them, and the two boys who were shooting were caught. One was named Peruniak, I forgot his first name. They caught him, interrogated him, and he confessed that Hryts has a submachine gun, that Hryts often shoots.

I didn’t know anything, I was sleeping in the evening, my mother was still doing something in the kitchen. There was a knock on the door, my mother opened it. In comes Vedmid [Bear]—that was his pseudonym, a rather plump guy, with a ten-shooter—we called the automatic Russian carbine a “ten-shooter.” He comes in and says, “Get up!”—so sharply. The insurgents had never been like that with me before… And I knew him, because sometimes they quartered with us. “Get dressed!” I’m getting dressed, and he hits me with a cleaning rod—whack! I’m thinking, “What is this?” “Quickly!” I got dressed, he took me across the road to a neighbor’s, an old woman, she lived alone. They sent her to a neighbor’s house. I went in, the windows were covered, a guard was standing there, and a tearful Peruniak was sitting there, poor guy. He had confessed during the interrogation. And a little shepherdess was sleeping there—there were two daughters, I think, Natalka Stakhera, younger than me—on the stove, and they hadn’t seen her sleeping. She hid and listened to everything, so she was a witness, we’ll get to that later. “Did you shoot?” I say, “No.” He punches me in the face. And that guy says, “Confess, because I already confessed.” I say, “I was shooting.” “Give me the weapon!” And twenty-five strokes with the cleaning rod for shooting. I say, “I don’t have a weapon.” “Then what were you shooting with? Confess.” “I already told you, with a submachine gun.” “Where is it?” “Someone stole it.” “What other weapons do you have?” “None.” He wrote down another twenty-five and turned to me: “Give me the weapons!” I say, “I have a *vtynok* (that’s a sawed-off shotgun) and two German grenades.” The kind with a long handle, like an egg. He leads me away, I already want to run, but I think, I wont yet, he wont beat me anymore. He’s angry with me, he has this little belly, he hides in those straw stacks. I’m carrying these grenades. A guard is standing on duty. We get to the house. Then he says, “Give me more weapons, you have more?” “I don’t know.” I don’t confess. He gives me five more strokes with the cleaning rod. “Get on your knees, ask for forgiveness!” “I won’t get on my knees.” I don’t know what came over me… He hits me on the head with the cleaning rod. True, he wrote it down later. “On your knees!” I knelt down. But I did sports and was learning holds back then. And I wanted to use a hold on him that would leave him on the ground. On my knees, it would be easy for me to strike him in a certain spot—and he would be down. But it’s a good thing that didn’t happen. (Laughs). I was a quick boy. In short, he recorded 72 blows—he hit me twice with the cleaning rod.

I didn’t ask for forgiveness, and the cleaning rod even bent.

He screwed the cleaning rod back into his “ten-shooter”: “Go!” I went outside, in the cold he hit me again with the butt of his rifle, and he didn’t record that one: “Go on, you bastard!” I didn’t know the word “svoloch” [bastard]—maybe we said “navoloch” somewhere, we didn’t have such a word. I was walking home and, I honestly admit, I thought about going to the NKVD right then, it wasn’t far from us. I’d go to the garrison, maybe a kilometer away, to the railway station. I’d go and call the NKVD. I had a rough idea of where they were quartered and where their *kryivka* [bunker] was. The NKVD would set up an ambush and get them. And I wouldn’t give anyone else up. That was my thought. But by the time I got home, though it wasn’t far, another thought came to me—I have a machine gun, I have a German MP submachine gun, I have Russian ones, I know how to shoot, I’ll set up an ambush myself with two submachine guns, so if one jams, I’ll use the other. The other one, the skinny one who walks with him, I won’t touch him—but this one, I’ll shoot him, riddle him with bullets! I thought that, and I felt better.

I came home. My mother asked what happened. “Nothing happened.” I went to bed, slept a little, in the morning I gathered the cows and took them to pasture. And Natalka Stakhera went to my mother and told her everything. My mother’s sister was a liaison—Kaziuk Anna, I think. No, my mother was Anna, the liaison was Ksenia. Unaware of anything, I come home and see Aunt Ksenia and my mother. I liked to sunbathe topless. But how can you sunbathe when you’re all black and blue, beaten? I came home, ate, and they were waiting. A third woman came too—I knew her, she collaborated with the Banderites in the forest. “Hrytsiuniu, why aren’t you sunbathing?” “Oh, I’m not feeling so well today.” “I hear, I hear it in your voice—come over here, take off your shirt!” “I don’t want to, Mom, I don’t want to!” She pulled the shirt off me—and my back was blue! That third woman immediately gets on a horse—women rode horses in our parts—and rides to the village of Nyrkiv. My relative, an SB [Security Service] man, was there. She went to the real insurgents and told them everything. And I know nothing, days have passed, I’m already preparing my action. It’s a good thing they hurried.

One evening I brought the cattle home from the pasture, my mother milked them, and I lay down to rest a bit. And we, the *opryshky*, had something to do, something to transport, to exchange some Tokarev machine gun—they used to mount Tokarev machine guns on tanks, they weren’t very good. I had made legs for it, because in a tank it’s on a mount, without legs. I had tools. My uncle was a blacksmith, so I could make anything. I made aluminum legs. When a plane was shot down once, that was our trophy. I found some aluminum tubes there, they were slightly oval. I made these light legs, with little feet so they wouldn’t sink into the ground. We tested all that weaponry we had a whole arsenal. I was getting ready to go there, having rested a bit—I had eaten, drunk some milk. The moon was already shining, it was summer. Suddenly I see—in the moonlight, a weapon glints, they’re surrounding the house. But they aren’t surrounding the house itself, but from the house. They’re surrounding the yard, from behind the fence, behind the wall, setting up machine guns, other weapons. I think: what is this, my God, Muscovites! But why are they setting up on top—Muscovites should be coming to the house. I went into the house—nothing. Strangers to my mother: “Good evening! Do you have a son?” “Yes, I do.” My heart is pounding—I see they are insurgents, but dressed as Muscovites. “Come on outside.” There’s a place where they chop wood. A chopping block. He’s sitting on the block holding my stick, the one I use to herd cows—it’s a thick stick, with a knob on the end so your hand doesn’t slip. We used to fight with the town boys—there were émigrés from the eastern oblasts and Russian-speakers. They were already in the Komsomol. The older Komsomol members would graze horses, and we’d beat them for grazing on our pasture. We had these wars, that’s why I had such a stick. He’s sitting there: “Oh, my dear boy, we’ve heard about you. Is this the kind of stick you use for herding?” “Oh, the cows are unruly, you need to…” “Uh-huh, we’ve heard what kind of cows—you fight over there.” “Well, yes, we fight with the town boys, because the Komsomol members graze their cows there on Sundays.” “You shouldn’t fight, even if they are Komsomol members. We’ve heard about you. You mustn’t.” And I’m thinking: my God, what awaits me now? And he says: “And how are you living? No grudges against anyone? We heard someone beat you up?” “No, nobody beat me.” “And you don’t hold a grudge in your heart?” “No, nothing happened.” I see that they already know that Vedmid beat me, and I think: My God, are they going to put me on this block now and beat me with that stick? That’s worse than a cleaning rod! I didn’t know what would happen. And he says: “Do you have a weapon?” “No, I don’t.” “We know you do. Hide it—the weapon will come in handy. You’re a good shot. Take care of the weapon. We know you know how to hide weapons. You took a beating—don’t hold a grudge in your heart. He has already been punished.” That’s what he said. And he didn’t order me to hand over the weapon, nothing. He tells me: “The Organization has punished him, and on its behalf, the Organization asks for your forgiveness.” I stood up and thought: My God, and I was planning an action! He talked to me like that, didn’t demand any weapons…

V.O.: And how old were you then?

H.H.: About seventeen… It’s hard to say. That’s what happened. We said our goodbyes, and they left.

After that, they started to trust me, they started taking me on missions—if I didnt confess to them, I wouldn’t confess so easily to the Bolsheviks either.

I told you how we wanted to blow up the Red Army club, didnt I? I started to tell you and got sidetracked. But that needed to be said because it happened before this.

In short, we were looking at what kind of mine was needed. I had a Bickford fuse, and we also had mines that could be detonated with a wire from a battery. But it turned out you couldn’t run a fuse wire there because they inspected the area before the movie showing. The explosives could be placed. The place wasn’t fully repaired, there was a small park, and from the park, there were shutters, boarded up. In front of that little club, there was a lot of old furniture, some barrels, and it was easy to place a mine there—the boys had already checked. They told me that and even drew me a rough plan. By the way, I was already drawing back then, so I could visualize it. So, even though the Bickford fuse is green, if you run it through the grass in the park in the summer, children play there and would notice it. And it was impossible to run the Bickford fuse right before the movie because it was guarded. So a radio-controlled or a time-delay mine was needed.

We didnt have one, so I went to learn watchmaking from Hryhoriy Chynych. By the way, he was living almost illegally in our village because his two brothers and sister were in the underground, and his mother was hiding in Vyviz (?). And he was a choir conductor and a church cantor—he had studied in Czechoslovakia. And for the underground, he was a specialist who repaired their radios and typewriters. And the underground printers worked on typewriters back then. And he also repaired weapons. He saw that I was a clever boy. By the way, after I was beaten, he kept in touch with me—I helped him move the typewriters. He trusted me, and I was pleased to be let in on such secrets. And then I met him in a camp in Vorkuta. They wanted to arrest him, he escaped from [unintelligible], and was wounded. I have a portrait I made of him—a very interesting family, but that’s another topic. And with one boy, his brother Yosypko, whose pseudonym was Bohdan, I was surrounded the last time, when they killed that operative Bohdanov—they killed him, and I managed to escape with his brother. But that’s another topic.

So, I was learning to be a watchmaker, and he knew me and was familiar with the underground. I was very happy about that—everyone was getting their watches fixed after the war because you couldn’t buy them anywhere. We learned how to take them apart, I learned how to clean them. I started by learning with an alarm clock, and then I moved on to wristwatches. And I needed an alarm clock to set up a contact in a mine. We had batteries that could be used for detonation. But that had to be placed near the mine. So, I learned what I needed, and that was enough for me. I didnt go to learn anymore. They brought me an alarm clock, and I already knew what to do. We tested it with a lightbulb, and then I took a small detonator and went into a cave (we have many caves), and wound it up. The two of us are sitting there, the clock is ticking, and then it goes off. The detonator worked—so the explosive would work too. We had hidden hundreds of kilograms of explosives—from mortars, from large mines, from infantry mines. There were minefields, we demined them and collected whole stockpiles, hid them in caves, stashed them everywhere. There were plenty of explosives.

Everything was ready. One night, two men come: “Get ready.” I got ready, everything was in order, and they lead me to the forester’s lodge. There was a house there where, I think, no one lived anymore—foresters used to live there, but they were deported. I go in—there’s a kerosene lamp, the walls are peeling, windows are covered, and there are many guards. As they were leading me, many guards stopped us and checked the password: “Halt, who goes there?” The password. I think, something serious is going on here. I go in, and a few *opryshky* are sitting there, some are already sad, some have bruises. And on the table, my mechanism is sitting on a white cloth. A man in civilian clothes, an older man: “Sit down, my boy.” I said, “Glory to Ukraine.” They answered. I sat down and was already trembling. That SB man shouts—it’s not just the NKVD who are fierce, all intelligence services are like that, partisan ones too: “Is this yours? Did you make it?” I don’t say that someone helped me, I just say yes. “We know everything—you even studied to be a watchmaker, maybe you [unintelligible] figured out that [unintelligible] those contacts.” Because he wasn’t stupid, Hryhoriy the watchmaker, but I don’t know who informed on him. And he keeps at me: “So you wanted to blow up the club?” And I say, “Yes.” “And do you know, you fool, that there could have been women and children there?” “But it’s for the NKVD, no one else is allowed in there.” “That’s not allowed! It has to be only the NKVD, women and children must not be harmed.”

By the way, I still think about it now: My God, and they called them bandits! But all revolutionaries blow up civilians—what are the Basques doing, what are the Chechens doing? So now I know—everyone does, right? But for them, you see, it wasnt allowed…

I’m just sitting there, and they are already interrogating the others. They had already been beaten, apparently. I sit and think—those from that village, those from this village have already died in Siberia. I’m holding up six fingers like this, he’s saying something to me, and I say to him: “You say it like this: women and children. But look: when they were deported, how many women and children died on the way? They are allowed to do that—but we are not?” So he comes up to me: “You snot-nosed kid, are you going to lecture me?..” And he pulls my ears like this, and then flicks me on the forehead. They didn’t beat me, by the way. I sat down then, and the one in civilian clothes, the old leader, comes up, all pale: “My boy, how old are you?” I told him how old I was—either seventeen or late sixteen. “Oh, my boy, you have golden hands! Don’t do that—study, learn about weapons, explosives, demolition, but don’t do this. The time will come—you will do it.” The others stopped shouting. Maybe they would have beaten me too—I don’t know, but they didn’t beat me. But those *opryshky* apparently didn’t give everyone up, because that Lemko wasn’t there—the boys must not have confessed. I didn’t even know all those *opryshky*. “Don’t do anything! Whoever wants to act—do it with us, but nothing on your own!”

And so we, the *opryshky*, disbanded. Bezruchko and I still did a few things, but I had already started working with the underground. And gradually, this Novy from Eastern Ukraine became my instructor, and I reported to them, although we still did a few things secretly. The *opryshky*, by the way, even had a couple of killings. Maybe that shouldn’t have been done. There was one man in our village who serviced the railway station, his last name was Leshchyshyn. They took an MP submachine gun from me. And when he became the secretary of the Komsomol organization at the railway station, our guys shot him. I already knew they were going to shoot him, I was against it. I won’t name names, so they won’t be prosecuted, they have families in the village now, so I still don’t talk about it. I was very worried when I was released—God forbid they find out I was involved in that, because the submachine gun was mine and I knew about it but didn’t confess during interrogation. And they have families now, they, thank God, were not in the camps… I was walking in the morning, and he was already lying there. He was in his railway uniform, that padded jacket or *telogreika*. It seems they shot him from the front—he was lying there, he had this railway lantern. It looks like they gave him a burst—a lot of cotton batting was torn out. They killed two or three people. This, obviously, shouldn’t have been done, but it was such a cruel time—what was done to us, our *opryshky* did back. That’s how it was.

They set up an ambush for one NKVD man, an officer of the internal troops, but he wore civilian clothes he was the “plenipotentiary” for our village, Kavukov. They also took a submachine gun and a carbine from me. I happened to be sick at home then, I remember, so I didnt go. But I would have hit him, of course. There were two of them riding, and he turned out to be a good soldier. A driver was taking him in a carriage, and near the district center, they shot from behind a concrete tomb and wounded Kavukov in the leg, in the thigh. About six months later, he was already coming to the village with a cane. But the other guy jumped out, ran away, and fired long, accurate bursts. Those boys fled, and one, as he was firing his submachine gun, you know how it recoils, a branch got caught in it and jammed his gun. And they escaped. That was another action.

COLLABORATION WITH THE UNDERGROUND

After that, I began to collaborate with the underground. I carried out rather difficult tasks—I even went to Chernivtsi for an operation, even stole documents. I could already open a window without breaking the glass, I could break glass so that it wouldn’t be heard. I took up sports. If someone with a revolver needed to be taken from a house for interrogation, I would tear through the thatch, the roof tiles, from the garden, climb into the attic when everyone was asleep, especially when they were drunk after a party… Or if something else needed to be done, I would just jump—I had slippers, like *postoly*, with a special sole so as not to be pierced by nails and not to make a sound, without heels, everything tied down, a mask on my eyes, a small flashlight. I would jump with a submachine gun. And if I needed to get back on the attic, I would jump up, lift myself, and I was already in the attic. I was such an agile boy. I carried out various actions, progressively more complex. The partisans were surprised that such a boy…

To tell the truth, I was driven not so much by patriotism, although my mother was a patriot, and my father, whom I don’t remember, everyone in our family was a patriot, we had that kind of upbringing, we were raised in the reading hall—but what drove me to that struggle in the post-war years was not so much for an independent Ukraine, but simply that I couldn’t stand to see that injustice. I couldn’t stand to see that cruelty—and I still can’t, by the way.

V.O.: You’re telling us you carried out so many actions—were you officially a partisan then?

H.H.: No, no, I lived legally.

V.O.: These were separate operations?

H.H.: Yes. I’ll also say that one day this wounded Kavukov went to my aunt (my uncle’s wife)—the one whose husband was in the “Galicia” division, who was a blacksmith, and the smithy was still there. There was some other blacksmith, and I was learning a bit of blacksmithing because it develops muscles, and I loved crafts. And the blacksmith was a Galician German, with one leg—like there are Russian Germans, Ukrainian Germans here. He knew German—and that was it. There was a German colony there, they spoke German, had their own school under Poland—that was allowed. He fought against the Germans, lost a leg, and returned from the front. A good blacksmith, but since his entire German village had been deported, and the Russians had nothing against him, he lived with his two daughters in the house of deported Poles at the end of our village. He had one leg and needed an apprentice, or as we say, a *cheliadnyk*, so I went to learn. I remember how funny it sounded in German: to strike with a hammer was “trouch.” And you had to know how to strike. He would strike with a small hammer…

V.O.: Indicating where to strike?

H.H.: Yes, yes, he with the small one, and I with the big one, and it was like music, such a rhythm. “Halt!” meant “stop.” “Get the drill” was “Durch Borch,” “drill through,” “Sing Borch” was “on the head,” “Schrubstak” was a “vise.” I learned everything in German—how to heat the forge, how to hammer. That’s what I did, but then I got so involved with the underground that there was no need for craftsmanship anymore.

IN THE FZU IN DONBAS

Kavukov kept coming to this blacksmith. He was very suspicious of me because I did sports, and in the village, they knew I was a nimble guy: “What are you doing here… twiddling your thumbs? Go study in Ternopil or Donbas, in an FZU!”—those were the factory-vocational schools at the time. There were raids, and boys were forcibly taken to the FZU. But I was still a minor—up to what age were you considered a minor?

V.O.: Probably until eighteen.

H.H.: So I was a minor, they had no right to take me by force. But there was a raid at night, and they took me. At the transit point in Ternopil, there were two older, skinny boys from my village—and they put me with them. And when there was a commission, they assigned me to a technical school in Ternopil. But then someone came up—and I was sent to Donbas again. I didn’t know it then and only later understood that they had taken me specifically to tear me away from the underground, to remove its influence. I arrived in Donbas—and again they dont accept me.

V.O.: What year was this?

H.H.: It was early forty-eight.

V.O.: And how did they transport you—under guard?

H.H.: Under guard, but the guard was probably unarmed.

V.O.: You weren’t transported alone, were you?

H.H.: Oh, many of us! At the transit point, they waited specifically… What a transit point—it was some hall, because Ternopil was heavily damaged, German prisoners were still repairing it.

V.O.: Where in Donbas did they take you?

H.H.: I’ll tell you in a moment. We were also waiting in Dnipropetrovsk, near a factory—they took boys from there too, added some from Chernivtsi Oblast and even from Eastern Ukraine—they had rounded up some thieves at train stations and sent them there too. They brought us to the city of Chystiakove in Donetsk Oblast, to the Lutuhin Mine, and again they put me with the older boys. They don’t accept me there either. I only figured out later why—I was well-developed physically, just looked young in the face. I even have a photograph from Donbas somewhere.

By the way, in Donbas I met someone from our district who was also caught—a guy named Mytsko. He was a Komsomol member, and I had beaten him up once for being a Komsomol member. There were older guys with him in the village, we beat them up too, because they were Komsomol members. And he was about three or four years older than me. And we even slept in the same room. There were about eight of us sleeping in the dormitory. They dressed us in uniforms, we did military drills, they taught us, I think, for three months to be a gas-meter reader—to measure gas. It’s not hard work in the mine—measuring gas. They give us lectures, we march to and from the dining hall. There were even some from Moldavia. [Unintelligible, special terms about fires, gas-measuring devices]. So we studied that, but I won’t talk about it at length.

Later, they came for me again, wanted to take me to a military school—some Suvorov school or something, I don’t know, all the way near Moscow. And again, they wouldnt let me go. They wanted to take me there because I had shown myself well in sports competitions: I did many pull-ups, jumped well, because we did sports there. We had leave, we could go into town in uniform. I remember picking apricots in a windbreak forest. Near the towns of Snizhne, Ilovaisk, and many others.

V.O.: Chystiakove—that’s Torez now, it was renamed.

H.H.: Oh, our dear city. Why did I start talking about that Chystiakove?.. Ah, I escaped from there. It was very difficult to escape, because when we went into town, older men in civilian clothes, guards, went with us. But there were escapes. By the way, when we were working, that is, doing our practical training, there were still German prisoners, and somewhere in the second half of 1948 they started deporting them. There were some agreements about the Germans, Slovaks, Hungarians. It’s very interesting: it was hot in the summer, and there was a lumber yard with timber for mine supports—back then they used wood to support the mines. It struck me, as an *opryshok*, that they were cutting down the Carpathian forest and bringing it for supports. And some of it was brought from the taiga. I thought: My God, why not bring it all from the taiga, why are they cutting down our native Carpathians? The Carpathians are already so deforested—that was the *opryshok* spirit speaking.

The Germans worked honestly. The Hungarians, in the summer, would go behind that lumber yard to sunbathe—they were lazy. But the Germans had such discipline that they even worked honestly for the enemy. They marched in formation, in ranks, they had officers or someone—with armbands, their own people escorted them, but without weapons. They were fed well, not like us—they had a military ration.

One day I decided to escape. How to escape? You could run away at night—go out to the toilet. It was a four-story dormitory, and there were no toilets inside the building, you had to go outside. The yard was lit, and two guards sat in front of the door. And there were guards on every floor. You can’t run away naked—in your long underwear and a shirt? So I took my clothes and work uniform, rolled them up, and threw them out the window into the park. I lived on the third or fourth floor. I threw them, and everyone was asleep, because they were tired. I go out as if to the toilet. And in the toilet, I had already scouted out how I could pry off a board and get into the park, run around, grab my things, and escape. The guards are sitting there, they don’t say anything to me, I went to the toilet, and then quickly, in my underwear, I went under the bushes, behind the building, grabbed my things, and left. And there were many small parks there, I got changed. And as a boy would fantasize: I had a bandage, I put my arm in a sling—since I had no civilian clothes—and started walking. I walked at night past some camps, orienting myself by the stars, by the North Star. And in Donbas, there are no clouds. When I got past Ilovaisk, I forgot where… [End of cassette 1]

V.O.: This is Mr. Herchak, cassette two, we continue.

H.H.: There was some small town there. I walked, by the way, past camps of German prisoners, they were lit up, dogs guarded them, I had to go far around them at night—it was hard walking. And then, hopping on some freight train, I made it all the way to Verkhivtseve—that’s across the Dnieper, somewhere in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast. There were all sorts of adventures, but that’s a long story. And so I made my way home.

NEAR HOME

They prosecuted people for escaping, though not for long, just a few months, but since I was a minor, they didn’t prosecute me. I hid right away, thinking they would prosecute me. But then they passed a message to my mother that they wouldn’t. I hid for a few months, and then, so to speak, I legalized myself and worked. I worked and continued to work with the insurgents, carrying out tasks. It got to the point where I had a Degtyaryov light machine gun, a couple of disk magazines, or as we called them, ammo—it was hidden in a rubber bag in the garden among the potatoes, properly greased. Why was this—because the insurgents went on operations, they had to be very mobile in the final years, and carrying such a weapon is heavy. So when they were doing some operation, I would stand by the road with the machine gun, and they would carry out the operation, and if any threat arose from the road, if the Bolsheviks were coming, I would have fired the machine gun to stop anyone from passing.

I’m getting ahead of myself. One day my neighbor had a contact—he broke, he lives in the village now, so I won’t name him—Ivan, he’s about two years older than me. They arrested him, and during interrogation, he confessed and said that I had a weapon. He probably also said it was hidden in the garden. And I was on a mission, we had crossed the Dniester somewhere, then waded through some river, I was wet in the cold water at night and fell asleep on the rocks at night, exhausted. I fell asleep towards morning and then fell ill with pneumonia. It wore me out terribly, there was nothing to treat the pneumonia with, I barely recovered. I was still walking around the yard like that, and the doctors told me not to sunbathe, not to walk around without a shirt, to wear even two shirts so as not to catch a chill. I was waiting to recover so I could go back to herding cows and helping my mother with work.

V.O.: Wait, how long were you in Donbas?

H.H.: You only had to study there for a little over three months, and I was there for about…

V.O.: And what time of year was it?

H.H.: It was the season when we were stealing apricots. And when I returned home, there were already early apples. It was 1948. I remember, I came home during the day—I know all the ins and outs at home, I came through the orchards to the house, climbed into the house through a window—there was a little window into the garden, we have a big garden. I climbed into the house, and there were a lot of apples lying there—apples, early pears. I remember it like it was yesterday, I came in, peeled an apple, ate it, left the peelings, climbed out of the house, and went to sleep in the neighbor’s yard on the hay, where there was an empty barn and house—they had all been deported to Siberia. I was afraid to be at home because I thought they would be after me. And my mother later told me that she came home, looked—oh, my son is here! Because I had peeled an apple and entered the house without keys. The harvest had just begun, I think. I remember how it was for me in that Donbas—the gases, the swearing, how coarse everything was! I came home as if to paradise—I swear, that was the impression.

Then, when that Ivan gave up the machine gun, one day after lunch, when I had recovered a bit, they surround my yard, conduct a search, and bring that machine gun from the garden. And then they arrest me. They arrested me and are leading me away.

V.O.: Do you remember the date?

H.H.: Oh, that’s difficult. It was the autumn of 1948, there was a frost, I remember.

They had just started digging potatoes. No, it was 1949, because I was already working with the partisans, going on various missions, and I had the machine gun. I went on all sorts of more complex missions, and we transported literature. They trusted me with that. I remember, many times we would carry something heavy, and I would think, what’s inside? But you’re not allowed to know. So when everyone was asleep, I’d stick my hand in, and there were books, and this was printing type. I was such a boy—curious and inquisitive…