An Interview with H. T. Hayovyi

for the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group

(Corrected by H. Hayovyi in May 2005.)

Audio fragment of the interview with Hryhoriy Hayovyi

Also listen to all audio files

V.O. It is June 16, 1999. We are in Kyiv at 23 Sahaidachnoho Street, having a conversation with Mr. Hryhoriy Hayovyi. This is Vasyl Ovsiyenko, recording.

Mr. Hayovyi, I am currently working with the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, although I am based here in Kyiv. We are preparing an “International Dictionary of Dissidents.” We have already prepared our part, the Ukrainian section—120 names. The list was compiled in Kharkiv, and in the final stage, with my participation. But after this, we must prepare a “Dictionary of the Resistance in Ukraine.” It should contain several hundred names. We will certainly try to include everyone who was imprisoned on charges of “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda,” “slanderous fabrications against the Soviet state and social system,” and also those who were not imprisoned but were involved in the resistance movement. We are covering the post-Stalin period up to “perestroika.” In other words, we are interested in what is called “dissidence” in the West. This term, of course, does not quite fit our reality, since, for example, believers or nationalists are not “renegades” from the dominant ideology; they have their own ideology. And “dissidence” itself was diverse. There was political and religious dissidence, there was a workers’ movement, and there was the movement to emigrate from the USSR (the Jews). But since this term is in common use, let it be; it’s hard to change it now.

Here is what we are interested in: a person’s biographical data—when and where you were born, where you studied. Of course, you should talk about your parents, especially if they were involved in the resistance movement. Your parents should be named, with their lifespans noted. But the main focus of this story should be your resistance to the regime and the repressions you faced. I imagine you are prepared to tell your life story. Especially since it is a part of our people's history. I tell everyone that history, unfortunately, is not always what happened, but what was written down. So let's record the truth, and let the truth, at last, become history.

H.H. No, it can be both what happened and what was recorded, but if it's not recorded, then it's as if it never happened.

I, Hryhoriy Tytovych Hayovyi, was born on February 4, 1937, in the village of Stepanivka, Mena Raion, Chernihiv Oblast—or more precisely, on a khutir [homestead] near this village, which is simply called Hay. There on the khutir, half the people were Hayovyis, and this half was further divided into two halves—the dark-haired ones and the red-haired ones. They were not related to each other in any way. One branch was red-haired, and the other was dark-haired. So, I belong to the dark-haired Hayovyis. But that’s just a joke.

My father, Tyt Hnatovych Hayovyi, was one of two men from the village who were drafted into the army, into the navy, before the revolution. He served in the Black Sea Fleet. You know Korniichuk’s “The Destruction of the Squadron”—well, he served in that squadron in 1917, on the ship Zlatoust. He was a Ukrainian revolutionary sailor in this Ukrainian squadron, which was scuttled, allegedly on Lenin's secret order, if we are to believe Korniichuk. I have one of my father's photographs, which he sent to his former girlfriend whom he had been courting. It is inscribed “October 25, 1917”—what a coincidence. My father is there in a sailor's cap and uniform. When the sailors were discharged, he returned home and was a member of the komnezam [Committee of Poor Peasants] or some other local self-government bodies, although he never joined any party. He was simply recruited as a revolutionary sailor. By the standards of the time, he was literate and enjoyed a certain authority among his fellow villagers. Our family descends from hereditary Cossacks, not peasants. My father's grandfather was relatively wealthy; he owned a mill. But somehow it was all squandered, and my father was considered one of the impoverished Cossacks. By his class origin, as they used to say then.

When the civil war began, my father's brother Matviy was mobilized by Shchors's men. But my father somehow managed to evade the Whites, the Reds, everyone. He didn't go to fight for anyone, but for a very long time, he also refused to join the kolkhoz, until he had sold off even the fire-pokers from his house. And then he had to join, because there was no other choice. And yet, in the kolkhoz, his fellow villagers elected him chairman of the audit commission—he was an honest man who could track all the machinations of the board. And he performed his duties conscientiously, and such performance, apparently, was not to everyone's liking. That was one thing, and another was that he had a sharp tongue and was careless enough to say at a pre-election meeting, “Why should I vote for someone I don't know at all and have never herded calves with?” And at that time, the candidates for deputy were the nation's beloved Joseph Stalin, and the other was some Kostiuchenko or another of our local guys. Well, his words were reported, and in 1938, my father was taken away. In 1939, he was sentenced, framed with an anti-Soviet article, and given four years in distant camps—and since then, there has been no word of him. He perished somewhere. He was rehabilitated 52 years after he was sentenced. So that is my short backstory.

My father was born in 1895, my mother in 1904. She was Mariya Sydorivna Hayova, maiden name Manyako. She was from the neighboring village of Voloskivtsi, so I don't know for sure, but she probably came from a peasant family. Because before the revolution, our population was divided into such estates: peasants, Cossacks, and townspeople, and there was also a clerical stratum in the villages.

V.O. Is your mother still alive?

H.H. No, my mother lived long enough to receive her pension; they gave her a pension of 12 rubles. That was in 1966, not long before I was released from the camps. A year later, she passed away. This pension of 12 karbovantsi was calculated based on an average monthly earning of 3 karbovantsi and 40 kopecks, as stated in her pension certificate. So the pension was four times larger than her earnings. I still have that document to this day.

Now about myself. My mother, of course, lived in poverty with three young children, and we were persecuted by everyone as children of an “enemy of the people.” Somehow I managed to finish the seven-year school in Stepanivka, admittedly with a certificate of merit for excellent studies, but where was I to go next? I had to continue my studies, so I went to the Donbas, to Makiivka, to my aunt, my father's sister Hanna Hnativna Andriyenko, and finished the ten-year school there. I graduated with a gold medal because I wanted to get into the university, and you didn't have to be very smart to predict that without a medal, I would hardly get in, considering my biographical data.

I was admitted to the Faculty of Journalism at Kyiv University in 1955. The dean at the time was Matviy Mykhailovych Shestopal, now a well-known public and political figure. He was the one who admitted me. I had a penchant for humor and wrote a sort of humorous piece during the interview, which he liked, and I was accepted without exams. And no one asked me about that ill-fated biographical data, that I was the son of an “enemy of the people.” Of course, they found out about all this later, and I, like all students of such an “ideological” faculty, was “under surveillance.” This was always felt, especially since I was never among the supporters of that system. Because I knew it, so to speak, from the inside; I constantly felt its pressure on me and tried, as much as possible, to resist it. Of course, there weren't many opportunities then, but I still thought that if, say, I became a professional journalist, then in my field, maybe I could do something, tell people the truth somewhere, and in this way, people would come to see that we were truly living under oppression. That was my somewhat naive position. This concerns the preconditions for my, so to speak, dissident biography.

The second precondition, which actually gave impetus to more active work, was the events of 1956, when Moscow's troops entered Hungary. This Hungarian turmoil stirred up many students at the time. It was in 1956 that the movement of the so-called Sixtiers began. True, I did not get caught in the very first wave of this movement—I was expelled from the university in 1957, not 1956. But a slightly older university student, Borys Maryan, a Moldovan by nationality, was perhaps the first Sixtier dissident from the university to be locked up in 1956. More precisely, he was arrested in the first days of January 1957. He served five years in the Mordovian camps.

V.O. Was there a long article by you in Literaturna Ukraina about this Borys Maryan?

H.H. No, in Literaturna Ukraina there was an article by Oleksa Musiyenko. I also wanted to write about Borys. I knew him very well; he influenced all of us young students because his program essentially contained the democratic principles that everyone officially professes now. For example, I was fascinated by one point of the program that was made public then—there were meetings, everyone was quoting him. It was written like this: remove the privileged caste of communists from power, allow the trade union movement, the youth movement, and so on to develop. These were democratic demands; he called it his program-minimum. He was imprisoned for this program-minimum, which he had let some people read.

V.O. And they gave him the maximum?

H.H. No, not the maximum, because the maximum for that article at the time was 7 years for a first offense, and he only got 5. I was expelled from the university a year later.

V.O. How were you expelled? What was the procedure?

H.H. My procedure was not exactly standard. After my second year, I volunteered to do my internship where I had finished school, that is, in Makiivka, Donetsk Oblast. And this was 1957, right when the “anti-Party group of Malenkov-Kaganovich-Molotov and Shepilov who joined them” made their move (and later they joked “and Hayovyi who weaseled his way in”). So, during my internship, they told me: “Write, brand these renegades with shame!” And I said: “Why should I brand them with shame, if they are all the same to me—both this side and the other?” “Don't you know this is a political matter, and for refusing to carry out an editorial assignment, you could get in trouble?” I agreed to a compromise: well, I can carry out the editorial assignment—and I organized an article on this topic from the secretary of the party organization of the pipe factory. The matter seemed to be settled, everything seemed to be in order. But then they still wrote a denunciation against me to the Central Committee, saying that the university was doing a poor job of educating its students, because they refuse to process letters from workers who were “branding the renegades of the anti-Party group with shame.”

V.O. What newspaper was this—a factory one?

H.H. No, Makeyevsky Rabochy, the official organ of the Makiivka city party committee in Donetsk Oblast. I was doing my internship there. Moreover, after the one-month internship, I worked there for another month—not on staff, but just for honorariums. They gave me an excellent reference from there. But when I came back for my third year and asked to finally be given a dormitory room (because I hadn't had one for two years), they told me: “What dormitory? We're going to expel you from the university!” “For what?” “Well, what do you mean, for what? There’s a signal.”

I didn't know what it was all about. They hinted that I had praised Trotsky somewhere, that I was covering for these anti-Party people. In short, they formulated it like this: “the anti-Party group of Kaganovich-Molotov-Malenkov, Shepilov who joined them, and Hayovyi who weaseled his way in.” That was the stupid rumor going around the university. And before that, they had been on my case for supposedly calling Vissarion Belinsky a wimp, a hack, and a person who hadn't learned to write but lectured others on how to write, and who also denigrated our Shevchenko. In a word, something semi-literary with hints of Belinsky's anti-Ukrainianism. This is common knowledge now, everyone knows it, but back then we had to figure it out for ourselves, no one gave us any clues. Moreover, if you dug up something yourself, they would start to sling mud at you. Such explorations, to put it mildly, were not encouraged.

For example, I spoke mockingly about Marx, about the political economy of socialism, saying it was just a handmaiden of politics and not a science at all, and so on. I poked a little fun at the Marxism-Leninism instructors—I wrote epigrams about them. In short, I engaged in a kind of political hooliganism, and therefore I was “under surveillance.” To my misfortune, I also kept a diary. No one knew about this. Why do I say no one knew? If anyone had read my diary, I would have been imprisoned immediately, because I expressed my views there frankly. But since they didn't give me a dormitory room, I carried all my notes in my student suitcase. I slept wherever I could, so I would put it under my head. When I went to lectures, I took it with me. So they couldn't plant an informant on me who could have read my notes when I wasn't there.

V.O. So where did you live?

H.H. As I said, wherever I could. I had to sleep in an unlocked lecture hall in the university's Red Building, in the attic, or I would “squat,” if possible, in the dormitories when upperclassmen went away for internships or were temporarily absent and a bed became free. Or those who had a dorm room would take in “squatters”—we would sleep head-to-toe… This was the order of the day back then, in the fifties; many students lived like that. And in the third year, just as they say about “old-timers” in the army, we were also growing up and had the right to demand our legitimate place. So I did, and that was the answer I got.

I started to ask: so show me, who wrote this and what did they write? Look at my reference! No one would show me anything—“Write an explanatory note.” Well, I went and wrote how it really was. It was the first and last explanatory note of my life, because after that I knew that it was like informing on yourself or writing your own sentence. This system was clearly organized. Indeed, I wrote the explanatory note—and on the very same day, the rector's order appeared: dismissed for failure to fulfill the academic program. Such an order. This outraged me: what does the academic program have to do with it? I didn't have a single C in two years, I passed my internship excellently, and I had a positive reference. That's what I told the dean. The dean at that time was Ivan Nychyporovych Slobodyanyuk. He told me: “Let the reference be like that. If we write that you were kicked out of the university for disgracing the title of a Soviet student, they will never take you back. But with this wording, you can still return to us.” I went to the rector. The rector at that time was Academician Shvets—he spelled his surname without a soft sign.

V.O. Maksym Rylsky used to joke that there are three words in the Ukrainian language with a hard ‘ts’: bats, pots, and Shvets.

H.H. This is how I met Academician Shvets. I went to him, thinking: well, after all, he's a Doctor of Technical Sciences, an academician—he must be an intelligent man, right? I'll tell him everything as it was, lay it all out for him—surely he'll understand? And you know what he did? He stood up and snarled at me: “We used to smash skulls of people like you! What are you—against the Central Committee? Get out of here!” And I said: “Wait a minute, maybe I'm in the wrong place? Maybe I've come to a district policeman? Are you sure you're Academician Shvets?” “Out! I don't want to see you again!” Just like that.

I thought, I'll go to Makiivka and find out, at least, who wrote this denunciation against me. I went to Makiivka, went to the editor-in-chief's office. He said: “Did I give you a reference? I did. That's it, I haven't written anything else and I don't know anything.” Maybe it came from the executive secretary, Borys Kofman? It was Borys Davydovych who had warned me that there could be trouble. I went to him. “No, no, I don't know anything. Maybe the deputy editor, Narbut, who oversees this matter?” I went to Narbut, and he just shrugged: “What are you talking about, did I ever even speak with you? No.” And he hinted that it didn't come from them, but from the city party committee—the denunciation must have come from there. At the city party committee, I found out that the third secretary, a woman named Zaporozhets, was in charge of ideology. I went straight to her for an appointment. Well, not an appointment, I burst in, you could say, brazenly and said that I was Hayovyi. “Which one?” “The one you wrote the denunciation about.” “What denunciation? It was a signal…” So I hit on the exact person who wrote it, by bluffing her. She said that the denunciation, or rather the signal, “came from Narbut and Kofman. Yes, there was such a call. What else could we do? You young people need to be taught a lesson!” “But,” I said, “after that call, if you received it, I worked for another two months—why didn't you talk to me then, if you wanted to teach or re-educate me?” “Are you going to teach me now?!” I wanted to say something else, but she threatened to call a policeman. I didn't want to get fifteen days, so I left, realizing that nothing would come of it. I had to, as Dean Slobodyanyuk advised me, earn a reference and come back to apply again: “We'll accept you if you earn a reference, and everything will be fine. Go work for a while.”

I got a job as a freelance correspondent for the newspaper Komsomolets Donbassa. It's the Donetsk regional youth newspaper. I worked in Makiivka, where I lived with my aunt, submitted material, everything was fine. I was there for about 20-25 days, earned a good reference. I came to Kyiv and asked Slobodyanyuk to reinstate me as a student. He asked: “Did you bring the reference?” “I did.” “Good, well done. We'll do it, but through the faculty's public bodies. They excluded you, let them support you.” I left the dean's office, and coming towards me was the “public body” in the person of the party boss Volodymyr Lazarevych Chornyi—a recent employee of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, he was the chargé d'affaires in Latvia—and the course elder, Oleksandr Arkadiyovych Novak, who still works at the editorial office of Kyivska Pravda. They asked: “Well, Hrytsko?” “Everything's in order. They said if the faculty's public body supports me, they'll reinstate me.” “This is not a halfway house.” I went back to the same dean. He threw up his hands: “Well, that's it. Didn't I tell you—the faculty's public body? Just yesterday, as soon as you left, two representatives from your own course came to me and said that you're not ready yet: you haven't realized your guilt, and you're not repentant. Sorry, my friend, I can't do anything against public opinion…”

Well, I thought, they'll draft me into the army, as they did with many others before in 1956, except for those who were imprisoned. Rather than serve for three years, I'll try to transfer to Lviv University. Many of our students who were kicked out of Kyiv University ended up in Lviv; they were accepted there. Especially since, according to my reference, I was expelled for not fulfilling the academic plan. And if the plan wasn't fulfilled, it was because of the internship, and at Lviv University, they didn't have an internship after the second year at all. I hoped they would transfer me there easily.

I went to Lviv. It was my first time in Lviv. I went to the dean, to the head of the department of party and Soviet press. I seemed to make a good impression on them—that's how I felt from our conversation. They said: everything is fine, we can enroll you—so what if you didn't complete your internship? We haven't had that internship yet. But we accept many expelled students from Kyiv, and then we get reprimanded: why are you doing this without our knowledge? Let your authorities write a little note saying they have no objection to us accepting their expelled student.

What was I to do? I thanked them for that—and that was the last they saw of me…

I thought, I have to find a job somewhere. I went to one newspaper, then another—no vacancies. I went to the obkom [regional party committee], thinking maybe they could get me a job at a newspaper. And they told me that in the city of Chervonohrad there's a small-circulation newspaper that needs someone. Where this Chervonohrad was—I didn't know. It was right when the Lviv-Volyn coal basin was being opened. And since I was sort of from the Donbas myself, the cards were in my hands. I went to that Chervonohrad. There was indeed a newspaper there, Budivnyk Chervonohrada (The Builder of Chervonohrad), where the editor-in-chief was an official who never read or signed the newspaper, only his name was on it—some Rastorguyev. The deputy editor-in-chief was studying by correspondence in her second or third year at Lviv University and was about to leave for her exam session. The executive secretary was about to go on maternity leave. There was one other literary worker, Fedir Rubel, who had been kicked out of Peremyshlyany for drunkenness and bigamy, so he had settled there.

V.O. What a team!

H.H. There was no one—but all the positions were filled. The only vacant position was that of a secretary-typist. And so they hired me for the position of secretary-typist, and together with this Rubel, I produced the newspaper for about eight months. And if he went on a drinking binge, I produced it myself. Moreover, we made this newspaper in Chervonohrad, but published it in Belz—Belz was then the center of the Zabuzky Raion, and you had to travel about twelve kilometers beyond the Bug River to get there. That's how I got my first real professional experience, from the end of 1957 to the summer of 1958.

I returned to Kyiv University. In the fall, they reinstated me in the faculty, and I graduated with a different class in 1961. At that time, Volodymyr Andriyovych Ruban had made his way into the deanship—he was an ardent KGB man, a persecutor of everything Ukrainian and progressive, in short, an odious figure, though not entirely mediocre. He wanted to kick me out of the university too. For publishing, as he said, a “bandit newspaper”—we published a wall newspaper in the dormitory that covered all four walls, and I was its editor. It was called “ZHLUKTO,” which stood for: Zhurnalistskyi Lehalnyi Universalnyi Kozatskyi Tvorchyi Orhan [Journalistic Legal Universal Cossack Creative Organ]. So, Ruban once called me in and said: “Are you publishing a bandit newspaper again?” I denied it: “No, what bandit newspaper? It's not a bandit newspaper at all, just, you know, one has to practice one's pen somewhere.” “Right, stop it by tomorrow, because I don't want to kick you out of the university again, because the persecution of the faculty will start all over.” A gentleman's agreement. I agreed: “Alright, I'll stop.” This was before New Year's in 1959–1960. At that time, the secretary of the faculty party organization was the late Leonid Suyarko, a well-known…

V.O. …atheist?

H.H. No, that wasn't him, his brother was the atheist; this one was a journalist. He taught the history of the party press. We went to Suyarko as a group, vying to suggest: “Let's publish a newspaper, we have all the means, we have talented guys…” He said: “Oh, that's a good thing.” And so, with the blessing of comrade Suyarko himself, the very next day, in the same spot where “ZHLUKTO” had been hanging, a new newspaper appeared under the name Parsuna. It had the same face, because the same guys were publishing it, but now with the consent of the party leadership.

V.O. And where was your dormitory?

H.H. At that time, we lived on a street that was called Zhertv [Victims’] Street, and later Heroiv Revoliutsii [Heroes of the Revolution] Street—it's above the Dnipro River, on St. Volodymyr's Hill.

In 1961, I graduated from the university, received an assignment to Luhansk, but worked there for a very short time. I was arrested there.

V.O. Where did you work in Luhansk?

H.H. In the youth newspaper. It was called Molodohvardiyets, and later Moloda Hvardiya. It was published in Ukrainian. There, as soon as I arrived, a conflict arose. A political one, you could say. Luhansk was always putting forward various initiatives. You know, for example, if you spit—write it down; if you did a good deed—write it down, for instance, helped an old lady cross the street—write it down in the Book of Republican Komsomol Deeds. Initiatives like that. For these initiatives, the Komsomol obkom was supposed to reward the proactive people. And if the Komsomol obkom gives awards, then the party obkom must approve these awards. So they sent me, as the youngest in the newsroom at the time, with this list for approval. Just to take the list to the second secretary of the party or whoever. They told me to be there at three o'clock. I arrived exactly at three—I'm a very punctual person, you could see that today: we agreed on ten, so at ten it was; and there they told me three, so at three o'clock I arrived, saying: I am so-and-so, I need to see so-and-so—“Wait five minutes.” I noted the five minutes and exactly five minutes later I opened the door without asking the lady who told me “five minutes.” I walked in to the responsible comrade, and he swore at me, like, “What are you barging in for?” I said: “Excuse me, I don't actually need anything from you. But I was asked to bring this note specifically to you at three o'clock, and they told me five minutes. I came at exactly three, then sat for another five minutes—so how long am I supposed to wait for you?” “How are you talking to me?!”—and he threw me out of his office in the most brutal manner. By the time I got back to the newsroom, they had already called the editor to tell him not to give such assignments to people like me anymore. In short, I didn't fit in…

I was corresponding with a friend, Maksymenko, who was the secretary of the Komsomol organization in the trust where the newspaper in Chervonohrad was published. We lived in the same dormitory, knew each other well. He was from Sumy Oblast, recently discharged from the army, but he didn't work for long—he got caught in some drunken brawl, served about six months or a year. When he was released, we continued to correspond.

And it also happened that one of Borys Maryan's associates, Ivan Pashkov, after serving in the army, ended up in our second-year class where I was studying. Since he only knew me from that class, and I knew his friend Maryan well, we sort of hit it off and became friends. So, Pashkov, this Maksymenko, and I decided to have an active vacation together that summer. We took our backpacks and started wandering “across great Rus'.” We went through the Donbas, then to the Belgorod, Tambov, and Kursk regions, to Moscow. We made such a circle and returned through the Tula, Bryansk, and Chernihiv oblasts to Kyiv. I kept a travel journal (it got lost later, though). Of course, we talked about various things, because we continued to communicate even after graduating from the university.

These travels of ours became the basis for the KGB to pin a sentence on all three of us: me, Pashkov, and Maksymenko. It was a case, of course, that was sewn with white threads, because there was practically no case there, but they decided that we had an anti-Soviet organization that we were going to use to create an extensive network to fight the existing system. And what did they actually have on hand? They had a few of our letters, a few notes. And they also planted an informant on me in the dormitory, so that he could read my diaries while I was on a business trip. And at that time, I was collecting jokes—there were a lot of political jokes about Khrushchev going around. All this was already at the local KGB; they knew all my friends, and to put an end to all this, they decided to create an “organization” for us. This “organization” did nothing. In principle, I allowed for the possibility that they would imprison me, because everything was leading to that, but to be set up so stupidly—I could never have imagined that. They gathered the three of us and cooked up a “case.”

They arrested me like this. I returned from some business trip to a raion in the morning of March 20, 1962, went to work at nine o'clock, was called to the editor's office, and there were already two men in civilian clothes sitting there. They put me in a car—and released me exactly five years and three hours later, that is, at 12 o'clock on March 20, 1967, at Potma station in Mordovia. That was the story of my, so to speak…

V.O. Pre-sidence.

H.H. Exactly, pre-sidence.

V.O. Now tell us about your sidence.

H.H. Next was sidence.

How did they cook up the case? I'm not a lawyer, but I knew that you can't be tried for your views. I understood that they knew my views perfectly well, but in order to pin a sentence on me, they needed at least someone to say that I was disseminating my views in some way. If they read my diaries, that doesn't mean I was disseminating them. No one had read my diaries except them. If anyone did read them, it was this Hrysha Hubin, whom they sent to me as an informant (supposedly a Red Army soldier discharged into the reserves) and no one else. For me to have told someone or agitated someone to overthrow the government—that never happened. Of course, I said that life was bad, but everyone said that. That is not agitation against the government. So they had nothing to pin on me. The only thing they achieved was to provoke my friend Prokopenko into writing an explanation about the differences in our views. They cornered him with the fact that “you were friends with Hayovyi—that means you have the same views, we can imprison you too.” So he wrote something like: “Hayovyi has these views, and I have these. We had disagreements.” He, for example, believed (the “he” being me) that all the shortcomings of our life stem from the shortcomings of the system, while he, Prokopenko, believed that the system was correct, but there were shortcomings that could be corrected. He wrote a note like that. He was called as a witness, then he started to squirm, saying he meant not the social system, but a system of shortcomings. In short, it turned into such verbal acrobatics. But even that was not at all a basis for an accusation. I did not plead guilty. And since I didn't plead guilty—I was “malicious,” and they made me the first one in the case. They gave the other guys five years between the two of them, and me five years all to myself. That is, Ivan Pashkov got three, and Mykola Maksymenko got two. Mykola broke down right away. He was, to some extent, their man; it's no coincidence he served in the so-called special department in the army. Besides, he had already been in prison once, so he probably thought that if he shifted the blame onto someone else, he would get less. In fact, that's what happened.

And they bought Pashkov a little too, or rather, he took the bait himself. The thing is, the KGB agents were familiar with my diary entries, and Pashkov was mentioned there a few times, in relation to our conversations on philosophical and literary topics. But we talked face-to-face, just the two of us. He knew that no one but me knew about those conversations. So if they knew about it, it meant Hayovyi had broken. They used such a primitive trick everywhere. After that, I have some kind of allergy or aversion to any kind of records or correspondence. For twenty years after that, I have hardly corresponded with anyone, because the thought is still in my head that they will read my letters and someone will use them against me.

We were tried in June, I think, on June 20, 1962. The date is in my release certificate. The Luhansk Regional Court tried us, in a closed session, as was the custom then. The court took nothing into account that could have defended us, and took everything into account that accused us.

V.O. Interestingly, in what language was the trial conducted?

H.H. In Russian. I refused a lawyer. I demanded that a transcript of the entire trial be made—they refused me that as well. I demanded that the trial be open—but the trial was closed.

V.O. Officially closed? Is it written that way in the verdict?

H.H. I don't know if it was official or not, but in any case, no one was allowed into the trial except the witnesses.

V.O. And did they give you a copy of the verdict?

H.H. They gave me a copy of the verdict, but by the time I got to Mordovia, it had disappeared somewhere. There were searches, you know. I'll have to request a copy of the verdict from the regional court.

V.O. And where did you serve your time?

H.H. I was in Mordovia near the Ruzayevka station; there is a settlement there called Sosnovka. It was the seventh camp, and then we were transferred to Potma, to the eleventh. I served my entire sentence in those two camps, the seventh and the eleventh of the “Dubrovlag” system. I believe I served it with dignity.

V.O. Tell us, what events took place there, what people did you know there?

H.H. I wouldn't say there were any very important actions. Maybe later, your generation, held some large-scale actions. But there, for example, a UPA soldier died once—so the guys organized a round-the-clock honor guard, if that can be considered an action. Well, and we Ukrainians organized a Holy Supper for Christmas. There were a lot of people, but it seems no one informed on us. Or maybe the administration knew but pretended that nothing had happened.

V.O. And what kind of people were there? Of course, those convicted for collaboration with the Germans, insurgents, and anti-Soviets. What was their ratio at that time?

H.H. First, I'll name the ratio by nationality. About 60 percent were Ukrainians. Then there were compact groups of Lithuanians, Estonians, and Latvians. There were Jews, who were usually imprisoned for their social-democratic beliefs, and there they became convinced Zionists. Ukrainians who were general democrats, with an anarchist leaning, became national-democrats there. You know—it was like this almost everywhere—anyone who considered himself a Ukrainian behaved or tried to behave decently, so as not to discredit himself and the nation in the eyes of others. Although, of course, there were different kinds of people among our brethren too. There were even Ukrainians in the NTS—the Narodno-Trudovoy Soyuz [People's Labor Union]. They spoke Russian, and sometimes it was hard to re-educate them. For example, some Kharchenko, supposedly from the Kuban region, short in stature, but very stubborn. Once he got in for this NTS, he remained an NTS member to the end. Those who served as policemen for the Germans, as a rule, were also policemen in the camp: they would wear an armband, or as we called it, an opaska, thereby openly demonstrating their cooperation with the punitive organs.

V.O. Yes, the “SVP” armband—“Soviet vnutrennego poryadka” [Soviet of Internal Order], or “Suka vyshla pogulyat” [The bitch went out for a walk].

H.H. We considered the armbands shameful and despised those “SVP-ers.” But there were also hidden snitches, whom we tried to avoid, and some of them, when the secret became known, would justify themselves to their fellow countrymen by saying they were supposedly just trying to play along with the administration, that they had signed a pledge to cooperate to ease their regime, but were not actually cooperating. Everyone tried to wriggle out as best they could. The attitude of our guys towards such people was varied.

V.O. Did you know any Ukrainian insurgents there?

H.H. There were many Ukrainian insurgents there. The Bandera wing dominated, of course, and the Melnyk wing was somewhat overshadowed by the Banderites. There were fewer Melnykites in general, and whoever was a Melnykite somehow didn't feel it was possible to display their views, because the Banderites overwhelmed them with their numbers and their, one might say, greater aggressiveness. We (I mean our generation, which did not participate in the uprisings but was for the Ukrainian revival) did not like this. We did not like these pre-camp, in-camp, and current disputes between the two wings of the OUN members. I have always expressed this directly to each of them, and I still do.

V.O. When I was imprisoned in Mordovia in the 70s, it was practically one community—the so-called Ukrainian anti-Soviets and the insurgents—only a handful of them remained. And what was it like in your time?

H.H. In our time, it was also almost one community, but in terms of numbers, the insurgents still prevailed. Reinforcements from the generation of national-democrats were also starting to arrive. These were very dynamic guys from Kolomyia, Lukyanenko's Lviv group from 1961, then the very young Melitopol group—Volodymyr Savchenko, Valentyn Rynkovenko, Oleksa Vorobyov, Volodymyr Chernyshov, Borys Nadtoka, and Yurko Pokrasenko, and also Ivan Polozok from Sumy Oblast, Oleksandr Martynenko and Ivan Rusyn from Kyiv…

V.O. From Kolomyia—is that the “United Party for the Liberation of Ukraine”? Do you remember their names?

H.H. Of course: Bohdan Hermanyuk, Yarema Tkachuk, Myron Ploshchak, Ivan Strutynsky, Bohdan Tymkiv, Mykola Yurchyk, Ivan Konevych. Our group of three people, from the Donbas. At first, we were in different camps, but then Pashkov and I were brought together in one, and Maksymenko was released from another camp. I didn't see him there, and I don't maintain any contact with him, as I consider his behavior to have been undignified. From Lukyanenko's so-called group of lawyers—Ivan Kandyba, Stepan Virun, Yosyp Borovnytskyi… They behaved differently, but I didn't notice any particularly close relationships among these Lukyanenko-ites. The greatest authority was enjoyed—both among the older generation and among us, the younger ones—by Mykhailo Mykhailovych Soroka. And another colonel, he seems to be still alive…

V.O. Maybe Shumuk?

H.H. No, Danylo Shumuk was not a colonel, I knew him well—he was just a stubborn Volhynian from the cohort of “eternal revolutionaries,” a former member of the Communist Party of Western Ukraine, who fought against the Poles, the Swabians, the Muscovites, the Yids, and the Khokhols—and got it in the neck from all of them, as they say. He wasn't with us for long, although he served, if I'm not mistaken, longer than anyone, kept to himself, always had his own opinion, and behaved quietly. Everyone respected him as a dignified person, but he didn't have a unifying authority. Ah, I remember: Levkovych—he was either a colonel or a general of the UPA. We always watched when they called Levkovych for a sentence review. This was when the minimum term was reduced from 25 to 15 years, so for those who had served more than 15 or were finishing their term, it was reduced to time served. Every year they would call Levkovych, and every year the same procedure was repeated. The prosecutor would ask him: “Is it true that you were awarded a silver cross?” And he would say: “Not silver, but gold.” “Well, you can go.” So he served all his 25 years. I was released, and he was still there.

Pryshlyak enjoyed authority. There were two Pryshlyaks there. For some reason, Yevhen Pryshlyak was not very respected. But Hrytsko Pryshlyak, Hryhoriy Vasylyovych, a mustachioed man, confident in himself and in the justice of his cause, a Cossack with a cunningly perceptive gaze from under thick eyebrows—this one was loved and respected. By the way, he is still alive. I even interviewed him recently; I can give it to you.

V.O. Thank you, I will transcribe it.

H.H. We also had a group from Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi, social-democrats. A slightly comical group, mostly Moldovan. There were two Ukrainians, the leaders—Mykola Drahosh and Mykola Tarnavskyi. These were Ukrainians, and the rest were Moldovans from the Chișinău music college. They organized a printing press in Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi. Drahosh was a teacher or the director of a school for working youth, and his friend Mykola Tarnavskyi worked at a printing house. He stole type from there, then they secretly produced leaflets and, to confuse the KGB, decided to send these leaflets to all official bodies—to editorial offices, to Soviet and party bodies, but in this way: send from Leningrad to Kyiv, from Tashkent to Leningrad. This was to show that it was a widespread organization and to hide where the trail began. And the content of these leaflets was that, well, Marx, of course, was wrong, but you, dear Marxists, are also interpreting Marx incorrectly. I'm paraphrasing the entire leaflet in a couple of words.

So, they produced the leaflet and gave a Moldovan from the first or second year, Mykola Kucheryanu, money for a trip to Leningrad to mail the leaflets to Saratov, Bryansk, or wherever else. But this young Moldovan figured: why waste this money on a trip when he could buy himself a suit, relax in his father's village, paste the leaflets there, and thus fulfill his revolutionary duty. And so he did. As soon as he left, the leaflet, of course, was discovered. They took this Kucheryanu, and he immediately confessed where, what, and how, who gave him those 20 or 30 rubles for the trip—and the entire group was arrested and sentenced. Drahosh told me that he was expecting the firing squad and had prepared for it. This was a revision of all of Marx, all of Marxism, such a widespread underground organization! And that Kucheryanu was initially a witness in the case because he helped to solve it. When the verdict was read—seven years for Drahosh, seven for Mykola Tarnavskyi, six and six and a half for the rest. And right there they arrested Kucheryanu and gave him five and a half years! At that, Drahosh burst out laughing at the trial. The judges thought he had lost his mind. But he was laughing because that Kucheryanu, who had confessed and thought he would be praised or even given a medal—he was also imprisoned. And everyone, it seemed to Drahosh, got a light sentence.

And in general, there in the zone, in my opinion, there were many such comical cases that could be well described. But much has already been forgotten. If I had started right away...

V.O. You would have been imprisoned again.

H.H. I wouldn't have had time to write them before I was imprisoned again. Because there was total surveillance.

V.O. Now is the right time to write! Although, who knows how things will be after the elections—maybe they'll start imprisoning people again?

H.H. I think if not us, they'll start with others.

V.O. Yes, but we have a different topic today. I'm asking about the younger generation in the camps. For example, Lukyanenko, Tykhyi, Lytvyn.

H.H. Lukyanenko was well-respected and conducted himself properly. Tykhyi was there, but unfortunately, I did not get to know him. But I was friends with Yuriy Lytvyn for a long time, even after we were released. He became particularly close with Ivan Pashkov.

V.O. Pashkov talks about a literary circle that was active in the camp, where they supposedly produced a handwritten journal.

H.H. That was all, in my opinion, a bit for show. Of course, there were many poets there. But four or five people would gather for coffee or chifir—Sinyavsky, Daniel, Lytvyn, Pashkov, Tarnavskyi. And Daniel would say: “Here we are, the elite of Russian society…” And there wasn't a single Russian there! There was also Albert Novikov—a Ukrainian half-Jew from Zhytomyr who wrote “Russian poems”: “I do not await novelty from Chronos, I affirm what is alien to these, preaching otherworldliness and the legitimacy of second Hiroshimas.” That's how he wrote. And I wrote a parody of him: “I'd give Chronos a punch in the nose! Who am I, who am I, who am I—with my red-bearded mug? With a mug, with a mug, with a mug, I am ever on the alert for all the Somovs and Semovs and Sims: life is ugly, without a Hiroshima—life is like a brothel, Chronos is a weirdo, Chronos is a moron…” and so on. Such were the literary exercises. Of course, they can be presented as some literary movement, or as a skit—it depends on who you ask. I was a bit involved in that as a satirist or humorist, and that's how I reacted.

V.O. You're a creative person, so something was always forming in your head. Did you manage to bring anything out of there? Or was it all just in your head?

H.H. We didn't call them books hidden in our boots, but under our padded jackets. I brought out a novella from there, “Torn Flowers.” I wrote it there, and finished it on the outside and published it in the journal Kyiv many years later, about three years ago.

V.O. Were those years hungry ones in the zone? What was the work like, what was the regime?

H.H. I wouldn't say we were hungry. But I'm not used to being picky about food. And the regime… I haven't seen any other regime, so I can't compare. In any case, we could freely walk from barrack to barrack; I was only in the punishment cell once, for 10 days. They wanted to put me in there many times, but they couldn't find a reason. But one time, some Estonian KGB agents came with “representatives of the public” to show off their achievements. They gathered people in the largest barrack. The Estonians gathered, but a crowd of people of other nationalities also wanted to get in. Suddenly, an incident occurred: the Estonian prisoners presented the guests from their homeland with a bouquet of barbed wire. Of course, there was a commotion, confusion, and I tried to push my way to the front from the back rows. They wouldn't let me, and I shouted: “Chto eto za svora?” [What is this pack of dogs?] And then Captain Sergushin: “Hey you, come here! What did you say?” “What did I say?” “You insulted us.” “How did I insult you?” “You called us a ‘svora’.” “I said: ‘chto za ssora?’ [what is this quarrel?].” And so it began—some heard “ssora,” some heard “svora,” and someone else said I had sworn, though I never swore. In short, they put me in for 10 days. That was my participation in these protest actions.

(H. Hayovyi. June 29, 1999. To all that has been recorded, I must add the following. First, I need to clarify my answer to the question about how it was in the Mordovian camps and how we were fed there. I, of course, exaggerated a bit, saying that everything was so good and fine. Concentration camps are, of course, not a resort. They fed us there on a budget of, I believe, 11–14 rubles a month. By modern standards, it roughly corresponds to the current “consumer basket.” In any case, for five years, none of us ever tasted any fruit or anything like that. But we survived because we were used to living and eating very modestly, when we were in the kolkhoz and when we were studying at the universities, not getting carried away. So it was easier for us to survive there than if we had previously lived in, so to speak, normal living conditions.

And now I want to clarify two more points. Of course, we did practically nothing for which we could be tried for specific actions. But we couldn't have done anything like that. In our ideological principles, we were not so much Ukrainian state-builders as anarchists, because the state was not our own and we perceived it as foreign—we fought against a foreign state. And now, when we have started to fight for our own state, we have encountered ideological problems related to the fact that we were not internally prepared for building our own state, but were psychologically aimed and had the resolve to fight only against a foreign state.

And the third thing I wanted to add. My creative work, of course, has had an impact on my fate, although one could say the reverse is also true. I want to read a poem, written in the fall of 1956 as a response to the Hungarian events. It consists of only four lines, is called “A Non-Anniversary,” and it goes like this:

Сто вісім літ – роки, роки...

Секретарі царів змінили,

І вже на танках шле вінки

Москва мадярам на могили.

This refers to 1848—the year 1956 was an echo of it. And here is my poem, written in 1961, when the so-called fateful program was adopted, stating that the current generation would supposedly live under communism—the Program of the CPSU. I then wrote a poem called “October Melodies”:

Чавкає осінь багнюкою,

Скиглить линяве щеня,

Ми з задоволенням нюхаєм

Прілі онучі щодня.

Нюхаєм прілі онучі ми,

Мовчки годуєм блощиць

І за програмою учимо

Те, що належиться вчить.

Хтось насякав на програмку ту

Жовтим густим сопляком.

Так би хотілось загавкати

Разом з линявим Рябком!

V.O. And at the same time, Ivan Drach wrote: “Oh, my sun-shining Program!...”

H.H. It's the same Program, which, by the way, figured in my trial, that little poem from 1956. I was telling you that it was hard to keep me under surveillance because I didn't have a dormitory room, so I carried all my notes with me in a suitcase, and no informant could read them. But later in the dormitory, Hrysha Hubin read them, along with the diary and the jokes, and reported me. Because in my correspondence, I was very proper and cautious, I didn't write anything like that.

So when people asked me why I was imprisoned, I would say: “So that Captain Abashchenko could become a major.” Captain Abashchenko handled my case, being the head of the investigative department for particularly important cases of the KGB in Luhansk Oblast.)

V.O. If you think you've more or less fully described your “sidence,” then tell us also about your “post-sidence.”

H.H. Well, post-sidence... This is more complicated, more complicated... After I was released, for a good twenty years, they didn't give me the opportunity to work in my profession. They practically didn't publish me anywhere. Moreover, they didn't allow me to work in a so-called ITR [engineering and technical personnel] position, and even less so in a worker's position, because I have a higher education. And if I didn't work at all, they threatened to kick me out of Kyiv for parasitism. It was like that for 20 years. And even in an independent state, things haven't improved much with finding a job, not to mention the means for a basic existence.

V.O. And yet you survived somehow? You lived somewhere. How did you manage to settle in Kyiv?

H.H. At first, I went to the Donbas. But I don't have any housing there. So I went to Kyiv. I got married and registered my residence here. And then they gave me an apartment because the building was demolished. But they gave me a worse apartment, and on top of that, they moved relatives in with us. This went on for a long and difficult time. There's not much to tell here—somehow it worked out. I want to talk about something else—how they wanted to recruit me to cooperate with the authorities.

We had a KGB representative from Kyiv there in Mordovia, Anatoliy Antonovych Lytvyn. I don't know what rank he reached, but there he was a captain. So, it turns out, he was in charge of the political prisoners who were returning to Kyiv for a while. One day he called me for a conversation, saying that, you know, you should be working in your profession. You're not being hired anywhere—so wouldn't you, as a reasonable person, be able to rebuff those people who are getting out of line? He started laying it on thick. And I said: “What, you want to hire me for your service? Then let's be specific: if you want me to watch someone, you know I got in trouble for my big mouth, and I'll immediately tell the person I'm supposed to watch that I'm watching them on the KGB's orders, because I can't do it secretly. If you want me to cooperate with you legally, then you know that my biography is not quite suitable for that. Give me a personnel form, but then we'll see if I can do it or not—because I don't have any special training for this.” I started on these “rotten” notes, and then I laughed and said: “You know what, Anatoliy Antonovych? I'm ‘rotten,’ and you're ‘rotten.’ Let's be frank. You offered me cooperation, but here's what I offer you. You know this work from one side, and I know the people from the other side. Let's write a book together, like Musiyenko and Holovchenko (Writer Oleksa Musiyenko and Minister of Internal Affairs Ivan Holovchenko co-authored several books. – Ed.). What, are you worse than Holovchenko? And you'll die, and I'll die, and there will be no trace left, not even a dog will bark…” He asked me to call him tomorrow. I called and asked about my proposal. He said: “When I retire—we'll talk then.” And that was it, no one from them ever approached me with such proposals again.

That was my epic.

V.O. And how did you get by all these years? Where did you work?

H.H. I worked various jobs—as a loader, and, of course, a stoker, whatever. Sometimes I wrote, sometimes I was published occasionally—all sorts of things happened. And now, when it's become possible to publish something—there's no money. Who supports the Ukrainian press now?

V.O. But you edited two of Levko Lukyanenko's books. I read your publicist writing—in Literaturna Ukraina, in Ukrainske Slovo, in Narodna Hazeta.

H.H. I did a lot of publicist work. Tomorrow, an article will be published in Ukrainske Slovo, which, by the way, concerns you too. I write some fiction as well.

V.O. And have you published anything about dissidence—your own or someone else's? Because I have to include such things in the bibliography.

H.H. Practically nothing. Even in the journal Zona, there were only my fictional works. I'm just planning to write something… While working at the journal Pamyatky Ukrainy, I participated in editing one of Levko Lukyanenko's first books, “I Believe in God and in Ukraine,” and wrote the foreword to it. I helped him with editing and arranging the book “On the Land of the Maple Leaf.”

There were several publicist publications in defense of justice that also relate to dissidence. For example, I spoke out against what I considered baseless accusations against Oles Berdnyk by Heinrich Altunyan, Stepan Khmara, and Bohdan Rebryk. Maybe there was something to criticize Berdnyk for, but to accuse him as they did, I consider indecent. I spoke out against it—not so much in defense of Berdnyk as in defense of justice. And in tomorrow's issue of the newspaper Ukrainske Slovo, there will be my polemical article aimed at correcting the views of Vasyl Ovsiyenko regarding the position of some of our dissidents in the presidential elections. I think you will also be interested to read it. I wanted to publish it in the same place where you published your article against Yevhen Marchuk, in the newspaper Chas, but they refused me there. This is by way of polemics. I'm not really speaking out against you there; I'm speaking out for justice. (Hryts Hayovyi. So Why Get into Politics Then? – “Ukrainske Slovo,” no. 24, June 17, 1999; also: “Den,” no. 132, July 22– A negative reaction to V. Ovsiyenko’s article “The Walls Compared Us, Like a Statute…”, “Chas,” March 26, 1999. – Ed.).

V.O. You once read me a very witty poem about Vyacheslav Chornovil, written back in your student years. Did you study together?

H.H. We were in the same year, in the same group. By the way, in this very same newspaper, Ukrainske Slovo, I recently published a whole article with reflections at the funeral of a student friend. This is also about Chornovil—what I think about these shenanigans with the split in the Rukh movement. And that poem was “The Ballad of the Sunbeams.” It was written back when we were studying at the university. Semi-literary, semi-humorous, but it captured something of Chornovil's character. He was actually like that, and he remained that way in character, with that kind of leaderism. It wasn't very apparent then, but it became apparent over twenty years. In general, I believe that a person should use their opportunities and their chance in their own time. If you don't use it, the train has left the station.

V.O. So you brought the recording of the radio broadcast from June 7, 1999. We'll copy it. And also your conversation with Hryhoriy Pryshlyak. When was this recorded?

H.H. It was recorded last year, but the date is not specified.

V.O. Thank you, let this be part of it too. If you feel you have completed your story, then just in case, give your phone number and address—let it be on record.

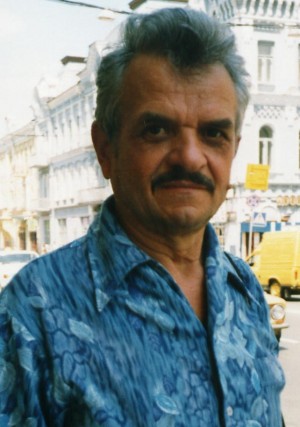

H.H. Kyiv-194, Koltsova Boulevard, 19, apartment 69. Telephone 276-35-08. And this drawing from 1965 was made by Viktor Mytarchuk—he was an artist from Zhytomyr Oblast. I don't know where he is now or what his fate is, but he was a very good artist. He drew this portrait of me in Dubrovlag, in the 11th camp.

Well, that's all.

V.O. Thank you, Mr. Hayovyi.