This translation of the original article was AI-assisted. The poem's translation from Russian to English is literal (line by line, word for word) and may fail to capture the original's rhythm, imagery, and poetic harmony. It was, however, edited to ensure the core meaning and metaphorical style of the original text are preserved.

***

A long time ago, back in the late 1980s, I had an idea: to examine how the KGB interfered in the lives of writers and the literary process. I envisioned it as a series of essays dedicated to various writers. But it never came to be; something else always seemed more important and necessary.

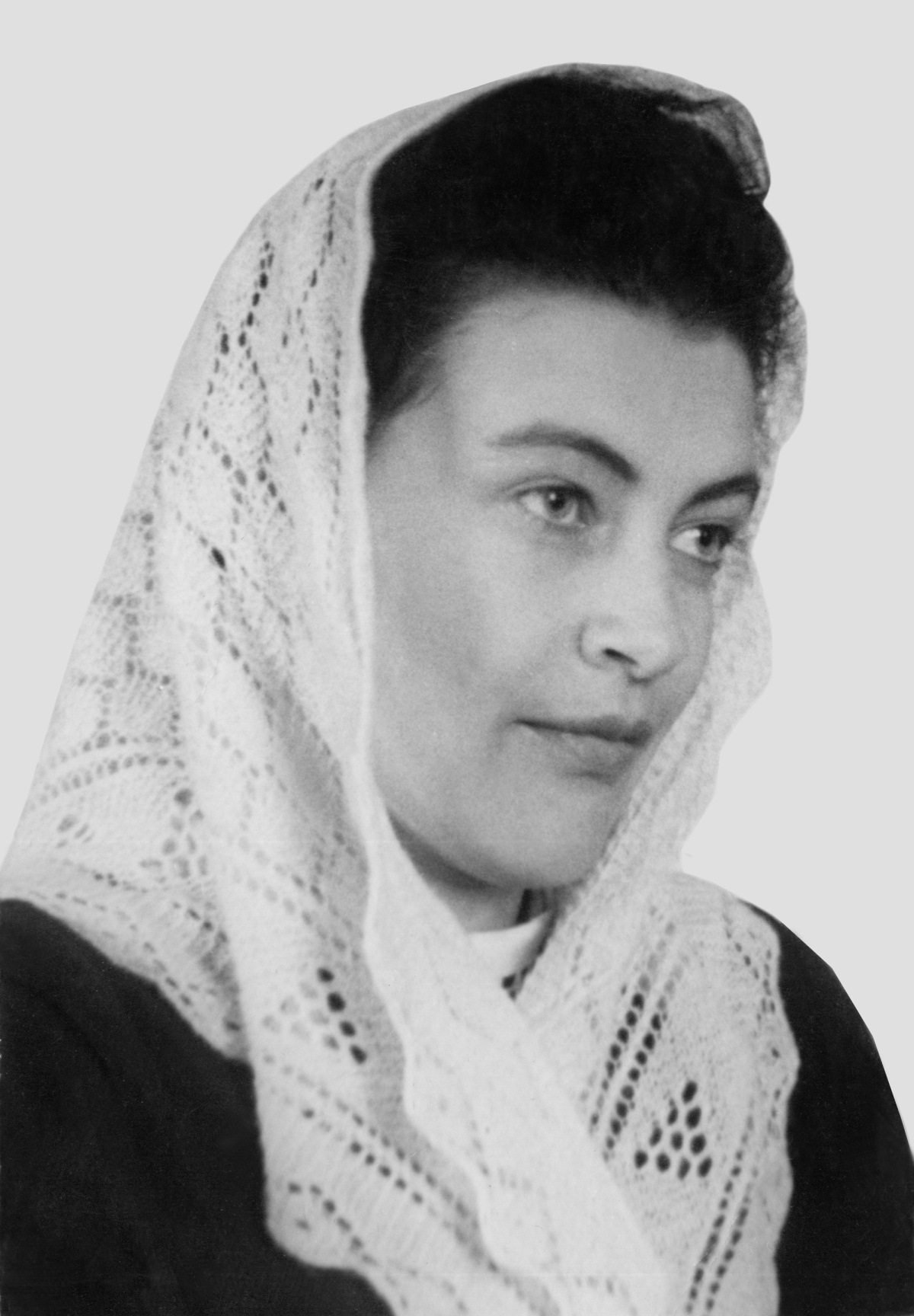

And yet, I decided to try to write such a piece about my mother, Marlena Davidovna Rakhlina (August 29, 1925 – June 5, 2010), who would have turned 100 on August 29 this year.

She began writing poetry as a child. As she searched for her tone and voice, growing up on the poetry of Pushkin, Lermontov, Tyutchev, Nekrasov, and Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy, her poems fell within the tradition of 19th-century Russian classical verse, marked by a poetic technique surprisingly advanced for such a young person. It was quite uncharacteristic of that era, as if the Soviet poetry of the 1920s and 30s had never existed.

Here are her poems, written at the age of 18-19.

POETRY

Life is only when She is again

on duty at night at the head of the bed.

And we do not know what to call Her.

Not memory. Not torment. Not love.

And the heart starts a dispute with the world,

and waits for Her, rejoicing and subsiding,

and here She, nameless sorrow,

comes and becomes poetry.

STORM

Oh, how we breathe in the night. We drink the moisture.

There was a whirlwind. The dawns blazed, trembling.

In my greedily open gaze,

they found shelter for themselves.

Born for a new life,

earthly space, sea foam

and human dreams gradually appeared.

So I met my lot,

my unlived years,

my desired freedom,

freedom from myself

PREMONITION

It cannot be that my verse was given to me

in exchange for passions, in exchange for earthly happiness.

It is quiet and gray, like the Neva water

in the beloved city where I was born.

I hear neither heavenly voices,

nor the sound of lyres, nor military legends,

I have neither scarlet sails,

nor wonderful countries, nor colorful garments.

And big cities do not rise,

no fair wind drives ships.

There is only the heart. And the heart will not let me

breathe easily and live freely in the world.

It is that melancholy for many thousands of years,

which cannot be cured by poetry.

To him love is - as to you - daily bread,

in exchange for which a stone is given.

And if I am so often cheerful,

I love laughingly, I do not cry at separation -

Forgive me! I haven’t lived to see the first fire, to be tortured by the cross.

In 1944, Marlena enrolled in the philology department of Kharkiv University. A group of writers gathered there who would later make a name for themselves in literature: Boris Chichibabin, Yuliy Daniel, Vladimir Burich, Grigory Pozhenyan, Vladlen Bakhnov, Irina Babich, Yuri Gerasimenko, Sergey Mushnik, Vladimir Portnov, Stanislav Slavich, Mark Aizenshtadt (who later chose the pseudonym Azov), Alexander Basyuk, Pyotr Nikolaev, and others. Here she found close friends—as it later turned out, for life—Larisa Bogoraz, Yuliy Daniel, and Boris Chichibabin. The young people met regularly at the Writers' Union's literary studio, where they read and discussed their poems with one another. Marlena was elected chairperson of this studio; she was a recognized authority there. Her poems were warmly received by the critic Grigory Gelfandbein, as well as by the poets Igor Muratov, Mark Chernyakov, Lev Galkin, Boris Kotlyarov, and Zelman Katz. She corresponded with Nikolai Ushakov, who lived in Kyiv and spoke favorably of her poems.

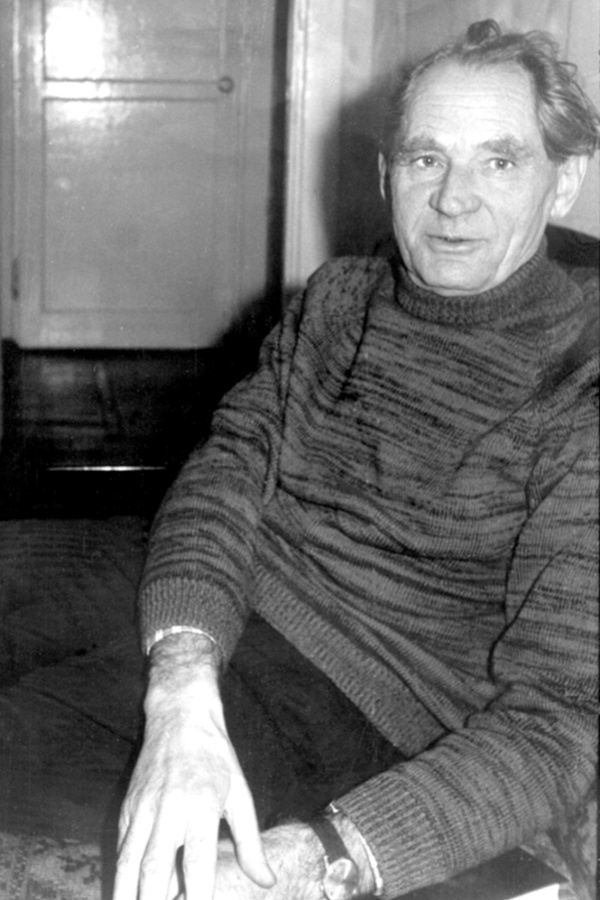

In the fall of 1945, the war veterans appeared in the philology department, among them Boris Chichibabin, who fell passionately in love with Marlena. Their relationship rapidly advanced, and they met every day. Boris became part of the family. He took additional exams to transfer a year ahead and be in the same class as Marlena. They were inseparable, and a wedding was planned for the fall of 1946. But… fate decreed otherwise. In the early spring of 1946, Boris was arrested and sentenced to five years in a general-regime labor camp. Marlena visited him in the camp three times. But he returned with a wife, Klavdia Pozdeeva, an employee of the camp administration. He soon separated from her and tried to resume his relationship with Marlena, but without success. As she wrote many years later:

...Look: it's me, it's you,

our children's laughter and children's hide-and-seek,

and we don't know - to the point of blindness -

everything that rushes at us hurriedly.

And when, having bombed "us",

the planes of fate fall silent,

it's incomprehensible from the outside,

who was abducted and where.

We look back, we are shocked,

we see - everyone in the appointed place,

and it's no longer possible to understand our child's dreams,

where the groom yearns for the bride...

This story is described in detail in the book of memoirs by Felix Rakhlin, Marlena's younger brother, “On Boris Chichibabin and His Time,” and much about it can also be found in Marlena's memoirs, “We've seen what happened...”. And now I return to the central theme of this text.

The resolution of the Kommunist Party Central Committee Orgburo, “On the Journals ‘Zvezda’ and ‘Leningrad’,” which led to the expulsion of Anna Akhmatova and Mikhail Zoshchenko from the Writers’ Union and the removal of Nikolai Tikhonov from his post as chairman of the Union board, was adopted on August 14, 1946. Based on it, Andrei Zhdanov, a member of the Politburo and Secretariat of the Central Committee, wrote an article published on September 21. Here is an excerpt from Marlena's memoirs on this matter.

“I was studying in the Korolenko Library when my friend Volodya Portnov presented me with a newspaper containing the resolution ‘On the Journals “Zvezda” and “Leningrad”’! The event was unprecedented, even by the standards of those times. And Zhdanov's report, which disgraced not only a first-rate poet but also a great woman who had heroically written and published poems about how she ‘did not abandon her land to be defiled by enemies’ (the report’s insults were almost unprintable, but nothing stuck to her), and this unnatural joining in one document of such different writers of different ages, talents, scales, and characters (oh, and this was not by chance, but for greater humiliation!). And this was at a time when Akhmatova had done so much for the country, for Leningrad, just yesterday! A book of hers had just come out after a long silence (!)…

The tragedy was repeated as a farce at our faculty, during a Komsomol report-and-election meeting. As part of their work with the younger generation, our department’s teaching staff decided to hold a ‘creative report’ by the young bards. It was implied that everyone had to repent for their ‘Akhmatovian sins’ (and we were told this in advance). One by one, our bards came out and ‘repented’ for the ‘Akhmatovism’ present in their work. All (ALL!) of them promised to reform. My turn comes, but in my view, I have nothing to repent for. I am (as they told me later) white as snow, my speech is incoherent, and my voice is quiet. But I try to explain that it is foolish and unnatural to compare the completely established (and long-established) Akhmatova with me, a beginner. I do not notice any pessimistic or unpatriotic motifs in my own work. ‘I am only just beginning to walk, and you are breaking my legs,’ I conclude.”

And then all hell broke loose! The professors, one after another, condemned the defiant student.

“And then everything becomes so unbearably disgusting to me that I take the floor and announce that the first post-vacation meeting of the Writers' Union Literary Studio begins in 20 minutes, I am the chairperson there, and I ask to be excused from the meeting (all of it—pure truth!)

A vote decides such things. Our dean, Reva, puts the question to a vote, first advising me ‘not to get heated and not to rush, as my future fate is at stake.’ But the assembly votes to let me go.

Reva is on the podium again. Now, threateningly, he speaks about my future. And in front of the assembly, which, apart from the first-year students, had seen me inseparable from Boris all year, he mentions the ‘scoundrel Chichibabin’: ‘whether he’s Rakhlina’s husband or whatever.’ And then our authorities violate democracy by deciding to re-vote. I don’t raise my eyes, but they say there are even more hands raised to let me go! ‘Well then, Comrade Rakhlina, if you don’t care... if you don’t understand that your Komsomol membership is at stake—then go!’ And without looking up at my comrades who had so unanimously stood up for me, I leave. For several days after that, the sea is stormy. The new Komsomol leader for our year, the demobilized Yan Gorbuzenko, informs me of the height of the waves. It even comes to the phrase: ‘End Rakhlinism in the department!’ And suddenly—silence and grace. As it turns out later, the university’s party leader, Polyakov, put an end to all the noise and commotion, saying: ‘Why are you pestering the girl, just leave her alone!’”

On August 8, 1950, Marlena and Felix’s parents were arrested: their father because, in 1922, during an intra-party discussion on just one issue, an organizational one, he voted for Trotsky’s resolution, not Stalin’s. He was twenty years old at the time! For this, he was expelled from the party in 1937, and he was saved from arrest only because, on the eve of it, he, a political economy instructor at the Tolmachev Military Academy, was transferred to teach in Kharkiv. And their mother, because in 1926, at the call of the rector of Leningrad University, a supporter of Zinoviev, then the leader of the Leningrad communists, she left a general party meeting at the university. They survived in 1937 because they had hastily moved to Kharkiv. Now, this past had caught up with them; they were both given ten-year prison sentences.

After graduating from the university in 1949, Marlena had been working as a teacher in a rural school in Berestovenka. There were almost no poems anymore. The arrest of her parents completely stopped her from writing poetry; she had other things on her mind.

The long hiatus lasted for seven years; she broke through only in 1956 after the 20th Party Congress1. She then wrote the narrative poem “Fathers and Sons” about her imprisoned parents and the children left behind (her father was still in Vorkuta at the time), in which she seemed to sum up her youth and young adulthood. The poem included this fragment:

I, with a healed wound,

without a path, without freedom,

my strange adolescence,

my "best" years.

Our youth is crushed

by war, then by prison,

our joy is hunted down,

they sent us begging.

And we looked like sheep

and "sons of the Fatherland",

hiding behind words,

that end with "stvo" and "isms".

And everyone was innocent

and submissive to fate,

moving hurriedly

not with their brains, but with their spines

We are contemporaries of pretentious,

crazy events,

we can erase nothing,

we can forget nothing.

And with sobs, with laughter,

and in bloody rags,

our poor glory will fly over the epochs.

From 1957, Marlena began writing again and wrote more frequently. She attended the literary studio at the Palace of Culture in Kharkiv, located at the Electromechanical Plant, where she met many young poets. Around 1959, Boris Chichibabin persuaded her to perform at a poetry evening at the Central Lecture Hall, claiming that she had been the most talented in the philology department back in 1946. The audience received her warmly, and from then on, performances at the lecture hall evenings became a regular occurrence.

In 1962, Boris Chichibabin had two small books published, in Moscow and Kharkiv. At the Writers’ Union, they persuaded Marlena to publish as well, and she had two books come out at the tail end of the “Thaw”2. The two books were “A House for People” (1965), one of a cassette series of tiny books featuring multiple poets, and “The Pendulum” (1968). If critics warmly received the first book, the second got only a single review-cum-denunciation, written by the critic Yuri Stadnichenko and published in the journal Prapor, which had a circulation twice that of “The Pendulum.” The manuscript of her third book, “What Doves Have to Fear,” which had already been accepted by the Prapor publishing house, was immediately returned. The explanation is simple: Boris Ivanovich Kotlyarov, who had previously welcomed her poems and urged her to publish, wrote a denunciation stating that Marlena was sending letters to an enemy of the people, Yuliy Daniel, in a labor camp, and that her poetry lacked a Soviet spirit. It was about Kotlyarov that Boris Chichibabin wrote:

Boris Zhuanych Kotelkov

wrote denunciations about me.

As a result, both Boris and Marlena were put on a list of writers whose poems were not for publishing. Their open communication with readers was cut off for almost twenty years. Nevertheless, both continued to write, without any hopes of being published.

I believe Kotlyarov did not write the denunciations on his own initiative; he was asked to do so by the KGB. Since the late 1950s, Marlena had been under the KGB's constant surveillance, as had Boris. In early 1963, she was summoned to the KGB, and shortly thereafter, we accidentally discovered that a listening device had been built into the ceiling. The upstairs neighbor was washing the floor, a floorboard came loose, and she saw the bug. She shared her discovery with an engineer at the housing office, unaware that this woman was a close friend of Marlena's.

Here is a brief description of the conversation at the KGB from her memoirs, “We've seen what happened...”.

“…Two of them, together and in turn, conducted a conversation with me, the stupidest of all I had at that institution, ‘before’ and ‘after.’

I am writing anti-Soviet poems! I couldn't agree with that! They latched onto one poem, a truly bad one, but by no means ‘anti-Soviet.’

No one hears them

until the time comes. (our poems)

They are written at night

and during breaks,

without them, we shiver

and freeze,

we couldn’t help but write them!

– ‘Until what “time”? What time are you waiting for?’

– ‘I refuse to talk about poetry with illiterate people!’

– ‘What do you think? Do we do it ourselves? We have experts!’

– ‘Your experts are illiterate too!..’”

And so it went for the whole day.

The next summons to the KGB was in 1974.

“Someone from the KGB called me and asked me to pay them a visit. As always, my curiosity got the better of me (I think this was a case where they wouldn't have brought me in by force), and I went. I was received very kindly by a certain young and disgustingly handsome brunette. When I inquired with whom I was dealing, he gave his name, but right then, like a jack-in-the-box, an officer popped into the room and addressed him by a different name. The ‘brunette’ looked at me with a smirk…

My handsome man stated that THEY (he actually said ‘We’) want to take me off their records, as they have lost interest in me (he put it more politely), but before that, they want to talk to me. For example, I have portraits of Solzhenitsyn hanging everywhere... And in general, they would like me to explain my views. I first assured him that I was not going to confess to a stranger in a notorious place. But then I flared up and informed him that I would never forgive the Soviet authorities for, among other things, what they had done to my parents. ‘But M.D.,’ he said, ‘you know, the 20th Congress…’ – Oh, no! – I replied, – that's not a proper response! If you were to tell me who specifically was punished for my parents' lives, then I might think about it, – I replied.

The conversation, nevertheless, continued. He asked me an odious question for those times: how I felt about Solzhenitsyn. I replied that I considered him a great writer. However, I was only familiar with him through the works that had been in the press. – And what about the books for which he was exiled? – But I haven't read them! Or do you want me to answer like your parrots: I haven't read it, but I condemn it!

(By this time, of course, I knew all of Solzhenitsyn, and he understood that. But he didn't insist.) Why did he call me here? – I wondered. And I got the answer right away. He asked me what Lina3 was writing. I replied that he must know that as well as I do!

– M.D.! – he said, becoming almost solemn. – I have no right to read those letters. If the prosecutor found out that I had intercepted and was reading them, I would be in big trouble! (‘Oh, sure,’ I thought.) – Give me those letters! – he asked eagerly. – I am very interested in Velina Markovna’s life (after all, you read them to everyone right and left, – he added these words to his request). Now I understood the reason for my summons and quickly wrapped up the conversation, explaining that I had not received her permission to do so. After which I left.”

In the second half of the sixties through the eighties, Marlena’s poems circulated in samizdat, were published in Kontinent and Russkaya Mysl, and were read on foreign radio stations. After the arrest of Genrikh Altunyan and his trial, Marlena wrote a cycle of poems dedicated to him and sent them for publication in Kontinent. Immediately after this, she was summoned to the KGB again. This time, the conversation was harsher.

“The conversation was conducted by the same man as last time (the ‘handsome one’!), but I wouldn't have recognized him. (It was he who told me we had already spoken ‘last time’.) He read aloud to me the poem ‘Look What They Did,’ published in the 30th issue of Kontinent, which was later printed three times in our domestic periodicals. But who could have imagined that such times would come?.. I will provide these verses so that my conversation with the handsome one is clearer.

Look what they did! They drew blood

and stuck a needle under the nails...

Some they expelled, some they brought in...

And we still sit, as we sat, in the corner.

Dear life! Beloved children!

Priceless cells! Dear pennies!

And there is no art - and okay, no need!

And there is no soul - we will live without a soul!

And there are many of us, many, oh God, how many,

how long, how sweet our life is!

And we have no God - we do not need God!

And there is no love - we will live without it!

The landscape of my Motherland never fades:

a crimson banner, and flame, and smoke,

and we still sit, still sit, guessing,

what they take away tomorrow? And we will hand it!

The handsome one. M.D., by distributing this text, you are undermining the Soviet system.

Me. Nothing of the sort! I wrote a poem and read it to my friends. What does the system have to do with it!

The handsome one: In your language, you wrote a poem and read it to friends. But in our language, it’s called something else. Intending to undermine Soviet power, you created and distributed a slanderous text that defames the Soviet social system. You have committed a crime punishable under Article 62 of the criminal code.

Me: You should fight words, not with repression, but with words!

The handsome one (with an ineffable, careless, semi-contemptuous intonation): Why?

I think everything that followed showed him WHY!

Me: Your repressions won't accomplish anything anyway. If you stand in any line, you'll hear talk much worse than any poems. Why are you rotting Altunyan in prison?

The handsome one: An old woman in a line, when we summon her, will immediately repent and renounce her words, but Altunyan won't.

I left after he warned me that ‘one more time’ (and even if I simply let someone read my ‘such’ poems), they would hand the case over to the prosecutor’s office without even warning me.”

“One more time” happened quickly. A month and a half later, “Poems for Altunyan” appeared in the 36th issue of Kontinent. Upon learning this, Marlena responded with the following poem.

But I still punched you!

And then - forget it,

and then let it be as it will be,

and it's all the same to me!

Although you are as Croesus in front of us,

and we as grass under you,

your sort will never forget,

what a piece of shit you all are.

But I still struck you!

And again - I am always ready,

even though you are the arbiters of our fate,

and we are water in a sieve!

Even though you hit us with an atom, a laser,

and we hit you with an insignificant word...

But the century will figure out

what's going on, and who is who!

On the other hand, the KGB is known to keep its promises. And Marlena earnestly prepared for imprisonment. In her poem “Farewell to the Sea,” she wrote:

I came to say goodbye: embrace me, sea,

in the face of a great misfortune, in the face of my last grief:

where my life will last,

there are no warm seas.

But the KGB decided not to repress the nearly 60-year-old woman, not wanting another scandal. And she, two or three years later, described her relationship with the KGB in a condescendingly humorous way—in the dialogue “The Poet and Citizen Boss.”

Citizen Boss (entering):

Still writing? Aren't you tired of it?

Well, well, write. Your business is to

write, and ours is to read you...

After all, you are not comparable to many.

The poet is silent.

Citizen Boss:

To tell you frankly,

To hell with your writings:

You are now a classic, a common idol,

and we are dragging you on our backs.

The poet is silent.

Citizen Boss:

What to do? Service! Daily bread

is not easy to obtain...

But we don’t have far to go

for an example. How much did they pay you at "Kontinent"

for the new verses?

The poet is silent.

Citizen Boss:

Still vigilant?

Still silent, like an old film reel? But keep in mind,

remember, you will be like a dog,

licking my old shoes!

The poet is silent.

Citizen Boss:

You are silent? Be silent! If not me, then the son-in-law,

if not he, then the brother-in-law - we will finish you off!

You will talk! You will tell, louse,

for how much are you selling Russia?

Where are you flying? What are you singing about?

Why are we following you?

Poet:

I seem to have fallen asleep. I don’t understand...

I dreamed something... I saw a prison again

in my dream... And in the window

a pearly pink dawn

between the bars... I am seventeen years old,

and somewhere there is freedom, somewhere the sun...

And rhymes, sonorous, like copper bells...

They begin to thunder -

and there is no prison... However,

here, it seemed, a dog was barking,

a mouse was squeaking,

or was a mosquito buzzing near the ear?

Seeing the Citizen Boss,

reproachfully:

Ah, so it is! In both dream and spirit!

As soon as I fall asleep, you make noise.

In the late 1980s, Marlena Rakhlina's poems began to be published in journals—in the sixth issue of Novy Mir for 1989, the 62nd issue of Kontinent, Literaturnaya Gazeta, and other publications. In 1990, her first uncensored book of selected poems, “Hope is Stronger Than Me,” was published in Moscow by the Prometey publishing house, with an excellent preface by Boris Chichibabin. In 1994, the Vest publishing house (Vilnius-Moscow) published the book “To a Friend in My Generation,” consisting of two sections: the first containing new poems from the early 1990s, and the second, an anthology of poems that Marlena considered her best. In 1996, Folio published the book “The Lost Poems,” which for the first time printed surviving individual poems written before 1949, as well as other poems from the late 1950s and early 1960s that had not previously been seen in print. In 1995, a book of translations of the brilliant Ukrainian poet Vasyl Stus was published: the bilingual “Zolotokosa krasunya/Zolotokosaya krasavitsa” (“The Golden-Haired Beauty”).

From the late 1990s, Marlena began writing prolifically again, and her poetics underwent significant changes: her former classical style was replaced by lively, colloquial speech. One after another, books of new poems were published: “October, Resembling July” (2000, two editions), “The Chalice” (2001), and “Crystal Words” (2006). She rewrote her memoir, “We've seen what happened…,” one last time, and it was published in 2008; she also wrote a novel in verse, “Philfac.”

An astonishing example of poetic longevity! I don’t know of anyone who wrote in Russian so much and so vividly in old age. This phenomenon still requires reflection.

Even after her death, Marlena Rakhlina had another book of Stus’s translations published: the bilingual “Palimpsesty/Palimpsesty” (2010), and a large volume, “Collected Poems. A Novel in Verse” (2015). Almost all of her works can be found on the website poetries.org.ua

1 It was known especially for the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev's "Secret Speech", which denounced the personality cult and dictatorship of Joseph Stalin

2 Khrushchovskaya ottepel (thaw), is the period from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s when repression and censorship in the Soviet Union were relaxed

3 This refers to the letters of Marlena’s friend Lina Volkova (Velina Markovna), who emigrated from the USSR in March 1971.