She fought for the rights of Ukrainians in the Soviet Union. For this, she was blackmailed with her child and sent to a labor camp in the north for 4 years. She managed to escape to the West, where she deciphered the microscopic letters of Vasyl Stus’s camp diary and began to demand justice for those unjustly persecuted in the USSR.

On November 8, 1936, in the village of Polovynkyne in the Starobilsk district of Luhansk Oblast, the prominent Ukrainian human rights defender Nadiia Svitlychna was born. She would have turned 85, but she passed away in early August 2006: Nadiia Oleksiivna died in the United States of America. According to her will, she was buried in the capital of Ukraine.

We discuss her extraordinary life with Yevhen Zakharov, chairman of the board of the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union, director of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, and a participant in the dissident movement.

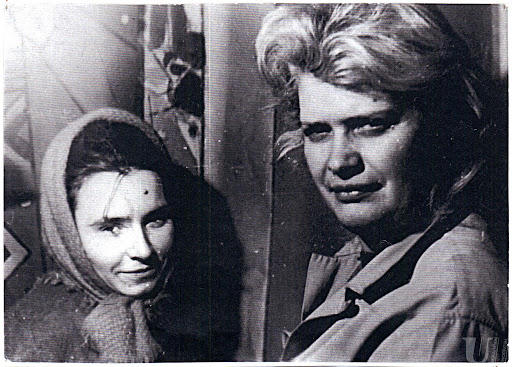

“Oh, how we miss the Svitlychnys, you can't imagine! It’s just, you know, a light in the window. She was a very likable person, always trying to help everyone, sensitive to others, and a very good friend. We were friends. She meant a lot in my life and in the lives of many other people,” sighs Yevhen Zakharov.

“Normal” Life Before Dissent

Nadiia Oleksiivna Svitlychna came from a peasant family. She had an older brother, Ivan, and a sister, Maria. As a girl, she studied at the Polovynkyne and Starobilsk schools (the latter being the only Ukrainian-language one of the 6 secondary schools in the district center).

In 1958, she graduated from the Faculty of Philology at Kharkiv University, majoring in Ukrainian language and literature. As a student, she went on expeditions throughout Kharkiv Oblast, collecting local dialects and folklore.

She then worked for 4 years as a teacher, head teacher, and director at a secondary school for working youth in present-day Antratsyt, Luhansk Oblast. For another 2 years, until 1964, she lived in her home village, teaching Russian literature at the Starobilsk medical technical school and working as a village librarian.

In 1963, Nadiia Svitlychna moved to the capital.

“She wanted to be closer to her brother, who was a literary critic and scholar, and a very important figure in the circle of Ukrainian Sixtiers. In fact, he was the center, the spiritual leader of the Sixtiers movement. And although she was working successfully in the Donbas—she was a teacher and a school director there—she was drawn to her circle of friends, to her brother, and so she moved,” says Yevhen Zakharov.

Nadiia Svitlychna worked as an editor in publishing houses, translated from Russian for magazines, was a research fellow at the Institute of Pedagogy, and simultaneously taught at an evening school in Darnytsia. She sang in the “Zhaivoronok” choir, and later in the “Homin” choir.

In the KGB’s Sights

During the repressions of 1965, a time of “purging” the Ukrainian intelligentsia, Nadiia Svitlychna was working in Donetsk with a group of monumentalist artists, including the artist Alla Horska and others.

There, they were to decorate the walls of Secondary School No. 5 with mosaics. It should be noted that 9 of those unique artistic, monumental mosaic panels have been preserved on the walls of that school to this day.

“She was helping, as always (laughs, - ed.), taking on completely different roles, not her own, but it was necessary to help,” recalls Zakharov.

The KGB took notice of Svitlychna after the events of May 22, 1967, near the monument to Taras Shevchenko.

For reference:

Ukrainian youth traditionally gathered annually at the monument to the Kobzar in the capital, reciting poems and laying flowers to commemorate the day of the poet’s reburial on Ukrainian soil. During such public ceremonies that year, the police arrested 4 participants without any reason, and the event turned into a spontaneous rally. The incensed youth marched in a column through the entire city center to the building of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, overcoming police cordons. There, they demanded the release of the detainees, and they were indeed let go. After that, the protesters sent a collective letter with dozens of signatures to the General Secretary of the CPSU, Leonid Brezhnev, demanding an investigation into the incident and punishment for those who had attacked the students.

“These were people who called a spade a spade, who did not want to put up with what Soviet society was imposing on them. And she, along with others, did what she felt she had to do,” says Nadiia Svitlychna’s friend about the events of that time.

Svitlychna often helped people who were already under KGB surveillance. In the autumn of 1967, she, along with three like-minded individuals, publicly stood up for the politician and dissident Vyacheslav Chornovil.

“She sent protests… Together with the two Ivans (Dziuba and Svitlychny) and Lina Kostenko—the four of them wrote a letter to Petro Shelest, actually on her birthday, November 8, 1967, in which they protested the trial of Vyacheslav Chornovil. They said it was a personal vendetta, a reprisal by people in power against a person who thought differently and dared to criticize the actions of certain institutions—that is, to exercise his constitutional right. She was at the trial; she was fired from her job for that, you see?” adds Yevhen Zakharov.

And in December 1970, in Vasylkiv, Kyiv Oblast, Nadiia Svitlychna, along with Yevhen Sverstyuk, would find her friend Alla Horska murdered. Nadiia organized the funeral and the erection of a monument on the artist's grave.

“The Soviet Special Services Blackmailed Nadiia Svitlychna with Her Son”

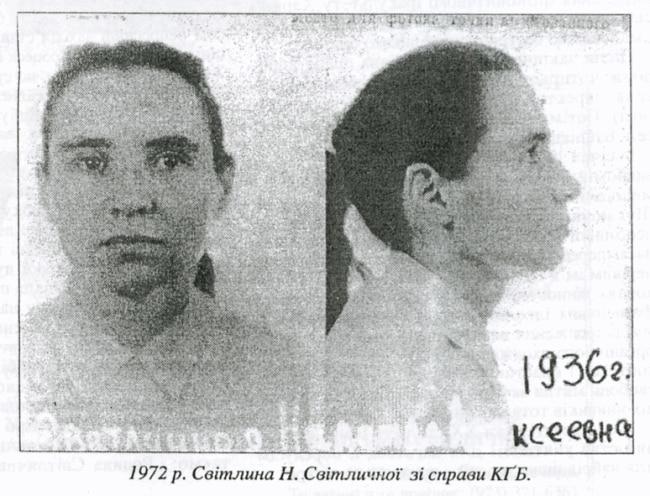

In January 1972, a wave of arrests swept through the capital of Ukraine and other cities and regions. In dissident circles, they are called the “January Mowing of 1972.”

“Repressions were repressions, but family life and love went on in parallel. And the KGB used this in their special operations against dissidents. They spread rumors about private lives, pitted people against each other, deliberately made them quarrel. Nadiia had several husbands, children from different men: from Danylo Shumuk, from Pavlo Stokotelny,” recalls the Kharkiv human rights activist.

Yevhen Zakharov notes: the special services blackmailed Nadiia Svitlychna with her son.

“So that she would testify—that was harder, blackmailing her that they would take her child away, to an orphanage! Yarema—her son by Danylo Shumuk, he was 2 years old—the KGB used him as ‘an argument for the investigation.’ A month before her arrest, they told her she would be arrested and demanded that she write down to whom she entrusted the upbringing of her child. And they took him to a children’s home in Vorzel. They took him from the nursery to this home when she was arrested on May 18, 1972. And only through the efforts of Lyolya Svitlychna, her brother Ivan's wife, did they manage to get him back and send him to his grandmother in Luhansk Oblast,” recalls Yevhen Zakharov.

For over a year after her arrest, Nadiia Svitlychna was held in the KGB investigative prison on Volodymyrska Street in the capital. A year later, she was sentenced by the Kyiv Regional Court under the Criminal Code article for “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”—4 years in a strict-regime labor camp. She served her sentence in Mordovia. And there, she remained true to herself and the dissident movement—along with other female prisoners, she actively participated in protests and hunger strikes. She wore a prison uniform with a collar on which she had embroidered ornaments with red thread. This garment can now be seen in the Sixtiers Museum in Kyiv.

Release from the “Most Perfect Concentration Camp”

Nadiia Svitlychna recalled her release as follows:

“I was released on May 18, 1976, exactly four years later. I immediately went to my mother’s, where my son was. The goal was to keep me in Luhansk Oblast. They offered me Lysychansk, they offered me something else. They offered an apartment, they offered a residence permit, everything at once. My sentence did not include exile, but they really didn’t want to let me back into Kyiv. They didn't have the right to prevent me. And so I went to Kyiv anyway. I stayed with my mother for a bit and then went to Kyiv. In Kyiv, of course, they wouldn't register my residence, and consequently, they wouldn't give me a job. In Kyiv, I couldn't get medical treatment for my child, because I wasn’t registered, and my son wasn’t registered either, because he had been deregistered just like me,” Nadiia Svitlychna later wrote.

So, on December 10, 1976, she sent a statement of renunciation of citizenship to the Central Committee of the CPSU, motivating this step with the brutal reprisal against Levko Lukianenko, Petro Hryhorenko, Vyacheslav Chornovil, Vasyl Stus, Stefaniia Shabatura, and other worthy people. She explained her choice thus: “It is beneath human dignity, after all that has been experienced, to be a citizen of the world’s largest, most powerful, most perfect concentration camp.”

And 2 years later, in October 1978, she went abroad: first to Rome, where she was received by the Pope, and on November 8, she arrived in the USA. And 8 years after that, in 1986, her Soviet citizenship was revoked. She did not accept US citizenship, although she could have.

“She remained a political refugee the entire time. And this was a principled choice of hers; this is very significant. Very few dissidents who moved to the States acted this way,” the human rights activist notes.

Nadiia Svitlychna Became the Voice of Condemned Political Prisoners in the West

At that time, the totalitarian system of the USSR continued to condemn and imprison critics of the government. So Nadiia Svitlychna became a member of the foreign representation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group and the editor-compiler of the American publication “Herald of Repression in Ukraine.” She continued to help the human rights activists who remained in Ukraine.

Despite the “winds of change,” the coming to power in March 1985 of a politician of a seemingly new generation, Mikhail Gorbachev, and his Perestroika of all levels of society, Ukrainian political prisoners continued to be held in camps. And to die. In May 1984, in the prison hospital of the strict-regime camp in Perm Oblast, after a prolonged hunger strike, Oleksa Tykhy died; in September of the same year, Yuriy Lytvyn died; and a year later, in the punishment cell of the same camp, under still-unclarified circumstances, Vasyl Stus died.

So, Nadiia Svitlychna collected documents of dissidents that managed to be smuggled out of the USSR to the West, says Yevhen Zakharov.

“She received these texts, handwritten on cigarette paper in a very small script. You could only make it out with a magnifying glass. And she deciphered it all and got it out. For example, Stus’s camp diaries take up about 20 pages in a book. Each of them was written on a piece of paper the size of a matchbox. It was Nadiia who sorted it all out, transcribed it, and it was published. This was first done in 1985, when a book in memory of Vasyl Stus was published in the States,” says Yevhen Zakharov.

Life After the UkrSSR

In the 1990s and early 2000s, Nadiia Svitlychna regularly visited Ukraine, and a great many people wanted to meet with her. “You had to schedule such a meeting well in advance,” recalls the interviewee.

At that time, doctors diagnosed her with cancer, and the woman courageously fought it. She held on for her children.

“That's a separate story. Her son Ivan was getting married, and she told herself she couldn't die until he was married. And she held on, was at the wedding, and even danced with him there,” recalls Svitlychna’s friend.

Nadiia Svitlychna died in the USA on August 8, 2006, and on August 17, she was buried at the Baikove Cemetery in Kyiv.

“Many people gathered, people came from everywhere, I came from Kharkiv. The coffin was carried from the House of Scientists on Volodymyrska Street, then along Bohdan Khmelnytsky Boulevard, and a large crowd followed the coffin,” recalls the participant of the dissident movement.

After Svitlychna’s death, her huge archive was transferred to Ukraine according to her will.

“She was the owner of a colossal archive! And after her death, according to her will, it was moved to Kyiv, and now it’s in the Sixtiers Museum, which is part of the Museum of Kyiv. But they still haven’t sorted it out… You can’t imagine how many documents there are. It was Mykola Horbal who did it; it was a separate job to bring it all from the States, and it cost a lot, by the way,” says Yevhen Zakharov.

And the library of her brother, Ivan Svitlychny, was donated to the Karazin Kharkiv National University according to her will.