On February 7, the Kharkiv Literary Museum hosted a lecture by Yevhen Zakharov, where he spoke about what dissidence is and what currents it had in the USSR, why and how people became dissidents, how dissent differed in Eastern and Western Ukraine, how many dissidents there were, and how the KGB fought against them.

Good evening. It is a great pleasure to be here at the Literary Museum and to meet with you to discuss this topic. Tonight, I would like to offer an overview of the dissident movement and, together with you, explore the nature and significance of this phenomenon.

The word “dissident” comes from Latin, where it means “one who disagrees.” It was typically used to describe those who opposed a generally accepted view, system of things, and so on. Initially, the word was used in a religious context to describe those who held non-canonical religious views. For example, in Poland, it referred to all non-Catholics; in medieval Great Britain, there were also religious dissidents. In our time, however, the word is usually used to identify people who disagree with generally accepted state directives and whose behavior does not fit within the dominant norms of the social system in which they exist. Such people are also called “freethinkers,” but there is a big difference here, because there are significantly more freethinkers. There are many people who think differently, but dissidents not only think differently—they also act differently. I will try to present to you a spectrum of different models of human behavior in the society that existed in the USSR, particularly in Ukraine, during those years. It is generally said that the dissident movement emerged in the late 1950s and ended in 1987, when the so-called “perestroika” effectively began. This is the period we must discuss when talking about the dissident movement.

I would like to propose an experiment. Imagine that you have traveled back in time 50 years and find yourself in the Soviet Union at the beginning of 1970. What kind of life awaits you there? The first thing to note is that the country is completely closed; it is impossible to leave. A trip abroad is like a gift from the authorities, the administration, the Party, and so on. This was especially true for trips to so-called capitalist countries—to go there, you had to pass a mandatory inspection at the KGB. And in every group that went abroad, there was always someone from this “office.” I think everyone knows that the KGB (I usually use the Russian abbreviation) is the Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti—the Committee for State Security under the Council of Ministers of the USSR. It was, in fact, a secret ideological police force that ensured that people living in the Soviet Union lived as they were prescribed. That they stayed within certain boundaries and never stepped outside them. So, the KGB watched everyone, everywhere they existed.

Typically, in every academic group at a university, there had to be someone they called a “snitch”—a person who was a *seksot*, an undercover collaborator of the KGB, who informed on the fellow students with whom he studied. In every work collective, there had to be such an informant, in every delegation going abroad, and so on.

Today, one can travel abroad; until recently, a visa was required, and now there is a visa-free regime with the countries of the European Union, but back then, it was absolutely impossible. I, for example, first traveled abroad in 1991, at almost forty years old, after the collapse of the USSR. Before that, I could not even dream of it; it was completely out of the question. Moreover, the KGB even forbade me to visit my relatives who lived in the border zone in the town of Baltiysk, the former Pillau on the Baltic Sea. Because the state border was there, it was impossible to enter the border zone; you had to get a permit from the OVIR. OVIR is the Otdel Viz i Registratsii—the Department of Visas and Registration. In effect, the permit was given by the KGB. And so, one fine day, I was forbidden to travel to Baltiysk, as was my mother. My father had his sister and a large family there; we were very close. But at some point, we stopped going there because we were forbidden. This example is quite characteristic.

Furthermore—one party, one ideology, and everything that follows from that. One line of behavior, and it was absolutely forbidden to deviate from it. There was censorship; you couldn't print what you wanted. There was the so-called Glavlit, which read absolutely every work published. Absolutely everything—in science, in art, in literature. Even when I was defending my dissertation in the field of “electrical machines,” my author's abstract had to go through this Glavlit. It's hard for me to say what they were looking for there, but nevertheless. And a great many things were forbidden. This, to be blunt, was a rather bleak existence in 1970, fifty years ago. And the question arises: what did people expect, what did they hope for?

Just recently, in August 1968, Warsaw Pact troops had entered Czechoslovakia, and virtually the entire leadership of Czechoslovakia was arrested. They were brought to Moscow, where they were forced to repent, to renounce all their plans, and so on. Incidentally, only one member of the government and leadership of Czechoslovakia categorically refused, signing and admitting nothing. He was simply placed in isolation, and they didn't even want to let him back into Czechoslovakia. And yet, the others managed to secure his release, and he left with everyone else. In effect, Czechoslovakia was occupied, and it was a coup d'état. And people everywhere in the Warsaw Pact countries had watched the so-called “Prague Spring” with great hope, when there was an attempt to create “socialism with a human face,” when they hoped for a much better life than before the “Thaw.” It should be said that in Stalin's time, there were also totalitarian regimes and political repressions in virtually all Warsaw Pact countries. And there was a “Thaw” everywhere, in some countries—earlier, say, in Yugoslavia, Hungary, in others—later, say, in the GDR it was in 1960.

In the USSR, the “Thaw” began in 1956, after Khrushchev's famous speech “On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences” at the 20th Congress of the CPSU. This very long report was read in all departments of the Communist Party at all enterprises, institutions, universities, and so on. That is, all the communists who came to these meetings heard it, a great many people. It was about Stalin's crimes, and Khrushchev revealed a great deal. In particular, he hinted that Kirov was murdered, and there were many other hints, and much was said openly. Then, in 1956, there was a mass release of political prisoners; about two million people returned. As Anna Akhmatova said, two Russias came face to face: the one that had jailed, and the one that had been jailed, and they looked each other in the eye.

At that time, processes moved quite quickly, and people, especially the youth, began to realize that they did not understand what was happening. They saw that what they had believed in, it turned out, did not correspond at all to what was reality. That history was rewritten, that much was manipulated, that everything was not as it seemed. That there were mass political repressions, that many people were killed, that everything with the war was not as they had been told before, and so on. The desire to know the truth prevailed then, as did sentiments of wanting to know more, to have more freedom than before, in Stalin's time, and this was especially characteristic of young people. If you look at recordings from those times, say, concerts by Okudzhava or Vizbor, poetry evenings of the late 1950s and early 1960s, youth gatherings on Mayakovsky Square where they simply read poetry to each other, you can see great enthusiasm, optimism, and a desire for something better in people. In this sense, the youth festival in Moscow in 1958 had a huge impact, when many foreigners came and, as it turned out, you could communicate with them, take books, and so on. Although it was under control, there was still a lot of it.

All this, in fact, launched the process of the “Thaw.” In addition, those who returned from the camps wanted to talk about what they had experienced. Then a flood of memoirs from former prisoners and such literature simply poured out, and in general, it was in vogue. Even in the prose of writers who had previously been completely neutral, a story would invariably appear where a very good person was repressed, ended up in a camp, returned, and the bad people who had oppressed him, and so on.

All this was within the paradigm of “bad Stalin, good Lenin”; it didn't go any deeper. A reassessment of Lenin's role had not yet occurred, and it didn't really get to that point, and such literature was not published, as is known. But, nevertheless, all this was happening, and it was developing. And the state suddenly began to realize that the ground was slipping from under its feet; it could no longer control everything as it had before. But the state leadership remained communist; this was a fundamental point. And there was a reaction, for example, to the events in Hungary, which were quite harsh and bloody, with many people dying on both sides. After the events in Hungary, the Soviet leadership began to fear the development of events. There was a meeting between Khrushchev and the KGB leadership at the beginning of 1957, and political repressions were effectively launched in the USSR.

Interestingly, all this happened side by side. On the one hand—freedom, poetry, literature, the magazine *Novy Mir*, and so on. And on the other hand—repressions against those who deviated from the party line, who wanted more than was allowed, and so on. In general, in the post-Stalin era, political repressions were at their highest precisely during this period, after Hungary. Of course, they were not the same repressions as in Stalin's time; they were different, but they existed.

Gradually, they began to “tighten the screws,” and Khrushchev was removed. There was still hesitation about what to do, but after the case of Daniel and Sinyavsky in 1965, the Soviet leadership finally decided that it was time to curtail the “Thaw,” all these freedoms, and set a course in that very direction. This was the first political trial where society fully supported the defendants; they did not plead guilty—nothing like that had ever happened before in the USSR. They defended themselves, their lawyers defended them, demanding their acquittal. All of society stood up for them; Western communist parties, Western writers, and others interceded for them. The idea was to create a political trial to intimidate the entire intelligentsia, but it turned out to be the complete opposite.

Yuliy Daniel

It is from the case of Daniel and Sinyavsky that the dissident movement is actually considered to have begun. Although, in my opinion, it should be traced back earlier, to the late 1950s, when there were quite a few underground communist organizations that wanted to change the system. They envisioned themselves as an underground party that would gradually expand, have many members, and when they were able, they would, so to speak, do all this. But all this was very quickly uncovered, and everyone ended up in the camps, and there was quite a lot of that.

Olha Riznychenko: And Lukianenko too?

Lukianenko, yes, that was the Ukrainian Workers’ and Peasants’ Union. There were such organizations in Ukraine as well. Olha just mentioned Levko Lukianenko; that was the so-called lawyers’ case, which became known much later; it was in 1961. It was an underground organization created by party workers. Levko Hryhorovych himself was a lawyer, by the way, and studied in the same class as Gorbachev. He was a member of the Communist Party and worked in a district party committee in Western Ukraine. The organization also included another lawyer, Ivan Kandyba, his friend, and a policeman named Virun. So, it was such an organization, but it was underground. But they already used non-violent methods of struggle. This era is characterized by the rejection of violence; it was all exclusively non-violent resistance.

Still, a couple of words should be said about the case of Daniel and Sinyavsky. They were writers who published in the West under pseudonyms. Andrei Sinyavsky's pseudonym was Abram Tertz, and Yuliy Daniel's was Nikolai Arzhak. Sinyavsky had been publishing since 1956, and this continued until 1965, while Daniel began publishing in 1960, so he published less. This went on for quite a long time until they were identified and arrested in September 1965.

Andrei Sinyavsky

Sinyavsky was a fairly well-known literary critic; he, along with Menshutin, wrote the book *Poetry of the First Years of the Revolution*—a detailed description of the poetry of that time. He was the author of a large introductory article to the edition of Boris Pasternak in the major series “Poet's Library,” which was the largest collection of Pasternak's works published in the USSR. This was in 1965, the very year he was exposed.

By the way, he was exposed in this way. He used a quote that he could only have seen in a *spetskhran* (special restricted-access library collection). This was noticed, and from there it was simple: they took a list of all literary figures who had access to the *spetskhran* to work there, and Sinyavsky's name was immediately identified. Immediately after that, they began to follow him, very quickly identified Daniel, and arrested them. They gave Sinyavsky seven years of imprisonment and Daniel five years, despite all the intercession. There was a very large movement for their release and to help them.

It was then that the dissident movement effectively took shape. People got to know each other and began to act together. A so-called “White Book” on the Daniel and Sinyavsky trial was created, which collected absolutely all the documents from this trial—the transcripts, the indictment, the verdicts, the final words of Daniel and Sinyavsky. This was created by Alexander Ginzburg with his comrades—Aleksey Dobrovolsky, Yury Galanskov, and Vera Lashkova. For doing this, they were again arrested and repressed; this was the Trial of the Four in 1967. After that, there was a large petition campaign in their defense, and so on.

(photo of Ginzburg)

Back in 1961, Ginzburg began to publish the samizdat journal *Sintaksis*, where he printed new poetry that had not reached the reader. Young Moscow and Leningrad poets were published there—Brodsky, Kushner, Akhmadulina, and many others. After that, some of them began to be published officially; there were many poets there who later became very famous. Four issues of the journal were published, and then this was also shut down, because samizdat could not be forgiven.

What is samizdat? The word was born back in the 1940s. There was a poet, Nikolai Glazkov, who was not yet published at the time, who would copy his poems into notebooks and sign them: “samsebyaizdat” (self-published-by-myself). Thus, this term was born and later became “samizdat.” That is, samizdat refers to works that are not printed by official publishing houses, that do not pass censorship, but are interesting to people, and they distribute them themselves, passing them from one to another. If I like it, I will retype it and pass it on. So, literature is classified as samizdat by the nature of its reproduction—typewriter, photographic method, various ways. Samizdat was very broad—both poetry and prose.

It is known that Solzhenitsyn managed to publish *One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich*, for which Khrushchev even planned to award him the Lenin Prize, but this did not happen, and a few more short stories. The last was published in 1966. *Cancer Ward* was already typeset in the journal *Novy Mir*, but it was banned, and so that issue of *Novy Mir* came out thin, without this novel, because there was no time to replace it with anything else. And all of Solzhenitsyn's prose was in samizdat: *Cancer Ward*, *The First Circle*, *August 1914*—the beginning of the epic *The Red Wheel*, and so on.

There were other wonderful works in samizdat, for example, Georgy Vladimov's *Faithful Ruslan*, which, in my opinion, is very powerful prose, the story of a guard dog. If you haven't read it, I recommend it. It is great literature, really. The first part of Yury Dombrovsky's dilogy, *The Keeper of Antiquities*, was published; the second part—*The Faculty of Useless Things*—was not published and was only in samizdat. Yury Dombrovsky was an old Stalin-era prisoner who wrote very well, and a large part of his works went into samizdat, although some were published officially, as was the case with Vladimov, by the way. The same was true for Voinovich, and so on.

Samizdat was philosophical, cultural, and historical. There were many historical works that talked about what history was really like. Because history was rewritten, it was manipulated. As my colleague and friend Vasyl Ovsienko says, history is not what happened, but what was written. This was precisely the case in Soviet times. Some things even made it into official print. There was an article by Vasily Kardin, “Legends and Facts,” in *Novy Mir* in 1966, where he recounted that there were no Panfilov heroes, that no one said, “Russia is behind us, and there is nowhere to retreat,” that on February 23, 1918, there were no battles and no Red Army, but only a decree by Comrade Trotsky on the creation of this army, and so on. That is, he recounted many facts about how established historical stereotypes were actually legends, and these things did not happen. But this could not be widely published in the official press. And when, for example, Doctor of Historical Sciences and Professor Alexander Nekrich wrote his book, a small brochure, *1941, June 22*, where he gave his assessment of what happened at the beginning of the war and why everything happened as it did, this book was very quickly banned, removed from all libraries and archives, from everywhere. It simply disappeared, became a rarity, and the same happened with other historical works.

There was a philosopher and culturologist, Grigory Pomerants; he died recently, a very famous, powerful philosopher. He was entirely in samizdat, almost never published officially, maybe only one, two, or three articles ever. His dissertation was never published; we recently published it, but it has not been published anywhere else at all.

The authorities also persecuted samizdat. In addition to book samizdat, there was also tape-recorded samizdat. In fact, all the songs of the bards—Vysotsky, Okudzhava, Galich, Yuliy Kim, Vizbor—were also not distributed officially. You could copy them, but the KGB also monitored who was doing it, conducted searches, and confiscated these recordings. They did everything to make the activity of amateur song clubs subside, and so on.

The same thing happened with nonconformist artists, who painted not as the authorities wished. There was no socialist realism; they were all modernists, and they organized exhibitions in the open air. There was a famous story when such an exhibition was crushed by bulldozers, and so on. It is well known how Khrushchev shouted at Ernst Neizvestny, and so on. And some artists even ended up in psychiatric hospitals, for example, like Mikhail Shemyakin. It's a famous story that he was declared mentally ill and ended up there.

So, the authorities decided to put an end to all this and began to repress those who distributed samizdat. There was Article 187-prime in the criminal code of the Ukrainian SSR, 190-prime in the code of the RSFSR, and similar articles in the codes of other Soviet republics. It was introduced in July 1967, and it punished anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda and the dissemination of knowingly false fabrications that defamed the Soviet state and social system. I will note that this was about distribution. The punishment ranged from a fine of 100 Soviet rubles to three years of imprisonment. This article was used quite actively. As a rule, when a person was imprisoned for this, they received the maximum—three years of imprisonment. In general, under this article, you could be imprisoned even for telling a joke—just by saying it was slander against the Soviet system. But the KGB—and they were the ones who sought out those who distributed samizdat—had a very simple approach. They would summon a person, and if they saw that the person was afraid of them, was intimidated, and renounced everything, saying they would never do such a thing again—they achieved their goal. This prophylaxis was, so to speak, successful, and this person no longer interested them; they would not tell such jokes anymore.

Where I worked, there were two young men who were very interested in international politics. They listened to Radio Liberty, the BBC, the Voice of America, and read everything they could find about international politics, being very knowledgeable about it. And constantly in the smoking room, when they went to a collective farm or to some construction site—as all young engineers, they were sent to work there—they would start conversations about it because they were interested. Both, as they later told, were secretly summoned to the KGB and told that behaving this way was wrong. “Think about your families, about your future. If you continue to behave like this, you will never get a promotion in salary or position; you will remain engineers at one hundred and twenty rubles. And if you continue, it will be even worse for you, because this does not suit us.” And they shut up, to put it simply, they stopped discussing it. So, in this case, it was also a successful preventive measure.

During such summonses, they always tried to turn people into informants and tried to get information on those who interested the KGB. If a person did not agree, was not afraid, did not want to have a conversation, let alone cooperate, then they effectively recorded their disloyalty to the KGB, and therefore, to the Soviet government in general. And they already became a candidate for future imprisonment; they would continue to be monitored, and so on.

The second political article that existed then was Article 70 of the criminal code of the RSFSR (Article 62 of the criminal code of the Ukrainian SSR)—anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda with the aim of undermining the Soviet government, as well as the possession of literature of such content. If under Article 187-prime one could be punished only for distribution, meaning the one who brought the samizdat, while the one who reads it should not be punished, here a prison term could be received even for possession. The first part of the article was from six months to seven years of imprisonment plus exile from two to five years. The second part of the article was, as a rule, for those who had already served one sentence under the first part, and there it was already from three to ten years of imprisonment and up to five years of exile. Moreover, those who were convicted under Article 70 (our Article 62) were classified as especially dangerous state criminals, and they were held not in criminal camps, but separately from criminals. And those who fell under Article 187 were with criminals in ordinary camps throughout the Soviet Union. By the way, one of the first to receive three years under this article was Viacheslav Chornovil. For writing the book *The Chornovil Papers* (Woe from Wit) about the fates of those who were arrested and convicted in 1965, during the so-called first wave of arrests in Ukraine.

Viacheslav Chornovil

From 1967, a total of 1,609 people were imprisoned under Article 190 in the Soviet Union. Under Article 70, from 1959 to 1987, 6,503 people were imprisoned in the Soviet Union as a whole. I will later explain how to calculate the number of convicts in Ukraine.

What I was saying about summonses to the KGB was so-called prophylaxis, and it was applied to those who behaved improperly: read samizdat, somehow got caught doing it, said something, and so on. From 1967 to 1974, 121,500 people were subjected to this prophylaxis, summoned to the KGB. From 1975 to 1986—an average of 20,000 people per year. This is quite a lot. If you take those who were convicted under Article 70 and look at who from their circle was subjected to prophylaxis, you will find that for every person convicted under Article 70, there were 96 who were subjected to prophylaxis. That is, this is a rather large group of people. As for those who were convicted under Article 190, for one convicted person, there were 25 who were subjected to prophylaxis. If you put all this together, you get that the total scale of those who were convicted under these two articles and fell under prophylaxis is approximately 700,000-800,000 people in the entire USSR. But that is far from all.

Who else interested the KGB, whom did they deal with? Those who tried to escape from this communist or socialist “paradise.” There were many such people. There is a well-known story about the “hijackers” who tried to hijack a plane in Leningrad in 1971. It is most famous because they were sentenced to death, the whole world stood up for their defense, and their death sentences were commuted to long prison terms. By the way, there was a case when a plane was indeed hijacked and flown abroad. People sailed on boats, secretly crossed the land border. There were many attempts; some succeeded. These people were standardly imprisoned for 10 years for treason against the Motherland. And they also sat in the same camps where especially dangerous state criminals were held, along with those convicted under Article 70. There were, for example, 2,240 such people from 1959 to 1974. Also a lot.

Next, a group of people like those who fought for freedom of emigration. There were also very many of them. This is another group of people who can be classified as dissidents. It began in 1970-1971; this is the period when the first people left the USSR, and this movement gradually became massive. Jews had big problems with this. Those who left first were considered almost enemies of the people. Those who were in the Party were immediately expelled, fired from their jobs; those who were students were immediately expelled from the Komsomol and from the universities where they studied, persecuted at all meetings, and so on. And they were not let out of the country; it literally had to be torn out with great difficulty.

In Kharkiv, the first such emigrants were in March 1971; I happened to know both of these families. One was the family of Haim Spivakovsky, who, back in 1948, as a very young man, was convicted as a Zionist and received ten years, but served less. The second family—they were very well known to me, because our families were friends—was Alexander and Velina Volkov. Alexander Volkov was a pianist and a teacher at the conservatory; Velina Volkova was an English teacher at a technical university. Likewise, they left the USSR with great difficulty, but they left. Then this stream grew and grew, but they had their own problems with the KGB and so on.

The next large group of people who were repressed by the Soviet authorities for “incorrect” behavior were the so-called religious believers. This is also a very large group of dissidents. These were people who belonged to various religious movements, in particular, Protestant ones. There were Baptists, conditionally speaking, “correct” and “incorrect.” The “correct” ones were those recognized by the Soviet authorities; they were official, registered. But there were also “incorrect” Baptists, who were much more numerous and were underground, meeting secretly, and were persecuted. A big problem for young men was military service, because Baptists and members of other Protestant communities are forbidden to take up arms; they cannot allow themselves to do so. And they massively refused military service. There was no alternative service then, and by the age of 28, they managed to receive two sentences under Article 72 of the criminal code for refusing military service. The first time—one or two years, the second—two or three years. There were many such people, several thousand. This category of people, by the way, has never been rehabilitated. Jehovah's Witnesses were treated with particular severity; this was always the case—both in Stalin's time and in Nazi Germany they were shot; they also refused military service there, went to camps or died in the Soviet Union. And in post-Stalin times, this particular denomination faced very serious repressions.

There were also problems for those who belonged to Eastern Christian denominations. In Ukraine, as is known, there were two banned churches—the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church, which was effectively banned back in the 1920s, and the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, which was banned after World War II. The UGCC was forced to become Orthodox; some agreed, some went to the camps, some also went underground. You will have a lecture by Myroslav Marynovych; he will talk about this in more detail, as it is very close to him. His grandfather was a priest of the Greek Catholic Church who was forced to convert to Orthodoxy; he mentions this in his memoirs.

Nelia Nemyrynska

This is Nelia Nemyrynska—a Ukrainian lawyer who defended dissidents. We published a book describing ten such cases. One of these cases was a trial where she defended Bidiya Dandaron, who lived in Alma-Ata and was a Buddhist, and was repressed for it. Nelia Nemyrynska was invited from Luhansk, and she went to Alma-Ata to defend Dandaron.

In general, there were very many people who were repressed precisely for religious reasons. There was a single article for which there was automatic rehabilitation in the laws on rehabilitation, at least in Ukraine and Russia. This was the illegal performance of religious rites, Article 209 of the criminal code.

I have listed almost all the groups that the KGB dealt with. Why did I do this? I believe that the best definition of the term “dissident” is the following: A dissident is someone the KGB considered to be one. A purely instrumental approach. That is, all those people who were watched... And the means of surveillance were the same: perlustration of all mail, surveillance on the streets, so-called *naruzhka* (tailing), wiretapping of telephones, searches of apartments, at work, and so on. All these methods were used very actively, and all this was, so to speak, rather joyless, but nevertheless, it could all be endured. So, all those people whom the KGB dealt with are dissidents.

It should be said that the Fifth Directorate of the KGB was created in that same year, 1967, at the initiative of Yuri Andropov. He had then become the head of the KGB of the USSR and proposed creating the Fifth Directorate exclusively for the persecution of dissidents. It was created, and in the central apparatus, there were four departments. One dealt with, conditionally speaking, democrats, human rights defenders. These were primarily samizdat distributors and those who spoke about freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, freedom of information, those who tried to know the true history, that is, they defended such general cultural, universal human, general democratic values. The second department dealt with national movements, the so-called nationalists. The third—with religious believers, religious movements. The fourth—with “refuseniks”—those who were denied permission to emigrate; there were very many of them.

There were also some socio-economic movements. But, firstly, they were small, and secondly, they were somewhat separate. There were attempts to create independent trade unions, by the way, precisely in Ukraine, precisely in Donbas. These people were also quite harshly persecuted. I can name two people, Volodymyr Klebanov and Oleksiy Nikitin, who ended up in a psychiatric hospital; I will talk about this separately.

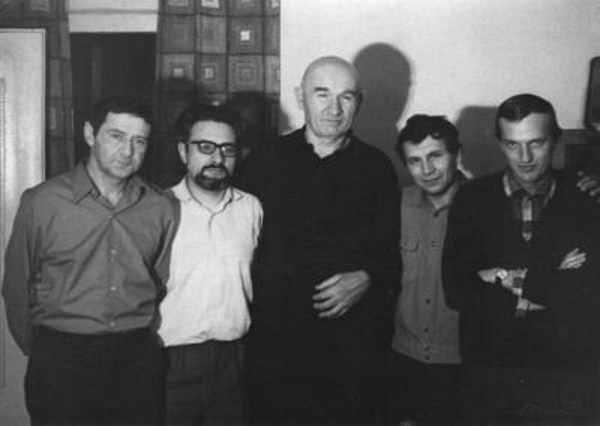

Arkadiy Levin, Henrikh Altunyan, Petro Grigorenko, Vladyslav Nedobora, and Volodymyr Ponomariov

This photo dates to approximately 1973. In the center is General Grigorenko, one of the central figures of the general democratic movement, but also of the national-democratic one. An ethnic Ukrainian, he lived in Moscow for a long time but never forgot that he was Ukrainian. He was one of the initiators of the creation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. Next to him in the photo are four people who signed a letter in his defense in 1969 and were repressed for it, exclusively for this. They received four years each. They are Arkadiy Levin, Henrikh Altunyan, Vladyslav Nedobora, and Volodymyr Ponomariov. I was very well acquainted with all of them and was close friends with them. I met them after they returned.

This story took place in 1969. Grigorenko went to Tashkent at the beginning of May of that year to be a public defender at the trial against the Crimean Tatars. He was deceived there, because he arrived when the trial had not yet begun, and he was put in a psychiatric hospital. Grigorenko was in very difficult conditions there. This was not his first time in a psychiatric hospital. The man was absolutely healthy, I would even say robustly healthy. But, nevertheless, this was one of the means of combating freethinkers, dissidents—to put them in psychiatric hospitals. Grigorenko was such a victim, one of many. Then his diary was made public, which he managed to pass through his lawyer to Moscow and which was widely distributed in samizdat, describing the difficult conditions he was in. Then, in May, just three weeks after he was imprisoned, a letter was written in his defense, signed by 56 people. This was the first appeal of the Initiative Group for the Defense of Human Rights—the first dissident association, which was created precisely in May of that same 1969. There were 15 people, and another 41 supported them with their signatures. In total, this letter was signed by ten Kharkivites who were acquainted with Petro Hryhorovych. Henrikh Altunyan was a member of the Initiative Group, and another nine Kharkivites signed. Of these four convicts, three were classmates; they were all born in 1933 and studied at the 36th school, and were friends. By the way, this whole company began celebrating the day of Stalin's death back in 1954 and celebrated it all the time they were able to gather. Volodymyr Ponomariov is a little younger; he was born in 1938.

It so happened that Petro Yakir and Viktor Krasin, who were the initiators of this letter, sent it not to the Central Committee of the CPSU, but to the UN Human Rights Committee, and did not even inform those who signed it. Out of the 56 signatories, only these four were imprisoned for three years. It was demanded of them that they say they did not sign the letter to the UN. None of them did so, just as none of the other signatories said they did not sign the letter to the UN; not a single person recanted. Now they have all, unfortunately, joined the majority.

Mustafa Dzhemilev

This is Mustafa Dzhemilev, who began to participate in the dissident movement very early on, and who, incidentally, was also a member of the Initiative Group for the Defense of Human Rights, one of the 15. In general, the movement of the Crimean Tatars for the return to their historical homeland of Crimea was one of the strongest, most massive national movements. Virtually the entire nation took part in it. And the methods of struggle they had largely determined what was done by other dissidents. In particular, the *Chronicle of Current Events*, its idea and form were copied from a similar bulletin of the Crimean Tatars.

The *Chronicle of Current Events* began to be published in 1968. It was a bulletin that collected information about human rights violations and political persecution throughout the USSR. It was regularly printed and distributed. It was the most famous publication, which everyone retyped and distributed. It was from the *Chronicle of Current Events* that foreign radio stations took their information.

Viacheslav Chornovil created a similar publication in Ukraine—the *Ukrainian Herald*; he was the initiator of this publication. The *Ukrainian Herald* differed from the *Chronicle of Current Events* in that it contained not only information about persecution, but also literary samizdat, and they even tried to include drawings by artists. These were large samizdat volumes that were also distributed. In fact, everything that was in it circulated separately. Ivan Svitlychny, for example, believed that it was better not to produce this publication, as it would provoke new repressions, which is what happened. But Chornovil did not listen to him and began publishing the herald. And Ivan Oleksiyovych himself actively distributed it. Chornovil managed to produce five issues of the *Ukrainian Herald*, after which he was arrested and imprisoned. The sixth and seventh issues were produced by Stepan Khmara, Oleksiy, and Vitaliy Shevchenko, while they were already in prison. But when Chornovil returned, he started the count over, began publishing the herald in 1987 with the sixth issue. They couldn't quite agree.

This period from 1965 to 1972 was a time when the dissident movement was very active. It was largest in the capitals, and in Ukraine—in large cities: Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odesa, Dnipro, and, of course, Lviv. This movement in Ukraine was very diverse. In Kharkiv and Dnipro, the general democratic movement predominated; there was little Ukrainian samizdat here. There were very few people who were later repressed as bourgeois nationalists for Ukrainian samizdat, for the struggle for national rights. In Kharkiv, only two people were repressed under Article 70. These were Ihor Kravtsiv and Anatoliy Zdorovyi. There was also Yuriy Dziuba, who emigrated after serving his sentence, but with him, everything was mixed; you can't say he was, so to speak, a pure national democrat. Both Kravtsiv and Zdorovyi were found with the work of Ivan Dziuba, *Internationalism or Russification?* This is the most famous book in Ukrainian samizdat, the most widely circulated; there were hundreds of copies, and it was translated into many languages and published abroad.

During this period, the Ukrainian and Russian movements were very close. In Moscow, they didn't even consider, for example, Lyonya Plyushch a Ukrainian nationalist, a Ukrainian democrat. Lyonya Plyushch, a Kyiv mathematician, actually started out speaking Russian; he became a Ukrainian later, in fact. He learned the Ukrainian language and began to communicate in Ukrainian. In Moscow, they considered him one of their own. But he did a great deal to translate Ukrainian samizdat into Russian, organizing this in Russia, and thus this samizdat became more widely known. That is, Plyushch was a kind of bridge between Ukrainian and Russian dissent. In character, especially in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odesa, and Dnipro, it was an intellectual movement, very close to the Moscow one. And in general, the road to the Mordovian camps, where people were imprisoned under Article 70, went through Moscow, and they all got to know each other then, became friends. Although many were already friends before, for example, Yuliy Daniel and Larysa Bohoraz, husband and wife, were very close with the Svitlychnys, since the 1950s. Because Yuliy Daniel translated Ukrainian poets into Russian, and Ivan Svitlychny was his critic, advisor, and so on; they saw each other often. And when Ivan was imprisoned, Larysa constantly wrote him letters in Ukrainian to the camp. The same was true for Yevhen Sverstiuk. That is, there were very close friendly relations between Ukrainian and Russian dissidents; one could talk about this at length separately.

In the period 1967-1972, there was, as General Grigorenko put it, an “unbridled rampage of democracy.” Samizdat spread, the authorities could not defeat it, and in 1972, they decided to put an end to it. Some special operations were carried out both in Russia and in Ukraine. In Ukraine, this was the so-called “General Pogrom.” On January 12, 1972, a great many people were arrested, about a hundred. About two thousand people were dragged in for questioning in these cases. Many were fired from their jobs. All Ukrainian projects were completely shut down. The creation of dictionaries, encyclopedias, musical groups—all this was completely stopped, effectively banned. People then lived under a Damoclean sword, that tomorrow they would come for you, take you away, so you had to be silent. Many were even afraid to speak Ukrainian on the street, for example.

By the way, I remember a story from that period in Kharkiv, when a Ukrainian language teacher who hung a sign in her Ukrainian language classroom saying “Cherish your native language!” was fired from her job for Ukrainian nationalism. If she had written “Respect your native language!” in Russian, nothing would have happened, that is absolutely obvious. In general, forced Russification was initiated then. In school, you could easily refuse to study the Ukrainian language and literature, and, to my great regret, it was Ukrainians who did this, many of them.

Zinoviy Antoniuk

In this photo is Zinoviy Antoniuk; he is a very close friend of mine and, in a way, a teacher. He is now 85 years old, very weak, and has been bedridden for the last two weeks. He is a very profound person and has written several books that I recommend to you. Zinoviy was born in 1934 in pre-war Poland, in the Kholm region. After the war, his family moved to Lviv; he studied in Lviv and later became a resident of Kyiv. Antoniuk, by the way, told me that he values the Ukrainian national-democratic dissent in the East much more and more seriously than in the West. Because in the West, it was a mass phenomenon and it was simple; it couldn't be otherwise. All of these are children and grandchildren of UPA fighters; everyone knows these songs, these traditions, holidays, and so on. In Western Ukraine, the national-democratic movement was a mass movement and it was not intellectual; it was populist. It included peasants and workers, in the countryside and in the cities. But the further east you went, the more it was concentrated in the cities, with almost nothing in the countryside. And the national factor became smaller and smaller; the defense of national rights became less and less prominent. Kyiv was a separate case in this sense; there were figures like Dziuba, Svitlychny, Sverstiuk, Stus, Antoniuk, and others.

Comment from the audience: Oleksa Tykhyy.

Oleksa Tykhyy—that's Donbas. He was in prison for too long...

Comment from the audience: That's what I'm saying. Yuriy Lytvyn. He's also from there.

Yes, but from Donbas, they were few and far between. But very bright ones. Ivan Dziuba is from there, Ivan and Nadiika Svitlychna too, by the way, from the village of Polovynkyne near Starobilsk. It's an interesting story; we could talk about it in more detail separately.

So, in 1972, everyone in Ukraine was imprisoned, and in Russia, there was the so-called Case No. 24. When Petro Yakir and Viktor Krasin were arrested, they gave everyone up, naming hundreds of names. The KGB officers drove around Moscow with Yakir; they would arrive at someone's place, and he would say: “Listen, I gave you this samizdat book, please return it...” That is, he simply turned everyone in, and Krasin did the same. They publicly repented, were given sentences, but very moderate ones, and were very quickly released. Krasin very quickly emigrated, and Yakir... He drank a lot, couldn't live without it. And it was with this vodka that he was effectively broken. They would give him a little to drink, and then say: “Come on, tell us more—we'll give you more.”

At some point, it became clear that there was no point in publishing the *Chronicle of Current Events* because they would only be writing about themselves. The entire circle had been exposed. Then the publication of the *Chronicle...* was stopped; it was only resumed in 1974. In fact, Sergei Kovalev was imprisoned precisely for this in 1974. The authorities triumphed then: everything fell silent; they had, so to speak, defeated everyone, imprisoned them, and so on. But, in fact, everything revived very quickly; this movement recovered quite fast. New people came.

There was a great deal of resistance in the camps, and one could talk about this separately. A lot of information was passed from there, entire books. For example, the books of Valeriy Marchenko, *From Tarusa to Chuna* and *Live Like Everyone Else*, he wrote in the camp and passed them out, after which they were published in the West. I know how it was done; maybe I'll tell you another time.

In 1976, the Helsinki period began. This was a wonderful idea by Yuriy Fedorovych Orlov, a prominent physicist, corresponding member of the Armenian Academy of Sciences, a professor. After the Helsinki Accords, the idea came to him to create a public association that would monitor the Soviet state's compliance with the agreements it had signed, which had become part of its domestic legislation. The idea was simply brilliant. And on May 10, 1976, Orlov created the Moscow Helsinki Group, which did exactly that. It included Petro Grigorenko, Lyudmila Alexeyeva, Sofya Kalistratova—a lawyer who defended many dissidents, and many others.

Petro Grigorenko convinced his old friend Mykola Rudenko, who was a writer, a prose writer and a poet, a former party organizer of the Writers' Union who had joined the party during the war. And Rudenko founded the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, which announced its creation on November 10, 1976. Those who joined these groups were mercilessly repressed. In Ukraine, there were ten founders of the UHG. Some of them were former Stalin-era prisoners, in particular, Levko Lukianenko, Oksana Meshko, Oleksa Tykhyy. There were also young people—Myroslav Marynovych and Mykola Matusevych. And two writers—Oles Berdnyk and Mykola Rudenko. The group was mainly engaged in the defense of national rights. Its documents were dedicated to other issues as well, although it focused more on this.

Quite quickly, the UHG was forced to report more about the repressions against the members of the groups themselves, who were being imprisoned one after another. And only Oksana Meshko remained at liberty, who was later also detained and given a term of exile. Although she wasn't imprisoned, thank God; she was many years old then, seventy. But those who were imprisoned joined the group again. In general, the Ukrainian Helsinki Group could be the topic of a separate conversation. Vasyl Stus, when he returned from the camp after his first sentence, also joined this organization, which became the reason for his second arrest and a term that he did not survive—ten years of imprisonment. This was in 1980.

I should also say something about punitive psychiatry; I have already mentioned it. This was one of the methods of combating dissidents, and it should be said that it was used very widely. Some researchers attribute almost a third of all Soviet dissidents as victims of psychiatric repressions. One can agree with this if one counts such a practice. For example, in Moscow, those who tried to get into embassies were simply detained by the police and sent to a psychiatric hospital. This was even mentioned in one of the documents of the Moscow Helsinki Group, that those who try to get into the reception office of the Central Committee of the CPSU, to the reception office of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, those who complain, are sent to a psychiatric hospital daily, 12-15 people.

This is indirectly confirmed by the fact that when, in 1988, the USSR, which had been expelled from the World Psychiatric Association after the case of Grigorenko, who was declared completely sane in the West, tried to return, they began to present facts of psychiatric repressions. And then, within a year, in the second half of 1988 and the first half of 1989, more than two million people were removed from psychiatric registers. This is a very large number, simply terrifying.

We had such a client, so to speak, Mykola Valkov, who had several sentences under Article 70 and was declared mentally ill. During his second term, before the trial, he was sent for an examination and declared mentally ill. Valkov was in a regional residential home for the chronically mentally ill in the village of Strilecha. I visited him many times, brought him parcels, and so on, supported him. His regime was gradually eased—at first, he could not go outside, then he was allowed walks, later—to leave the hospital grounds, then he was allowed to travel; he visited us many times, even came to the KHPG office, and so on. It ended with his complete release. So, his doctor, a very elderly man who had previously been the head doctor of this residential home in Strilecha, told me: “Can you imagine, the secretary of the district committee calls me: ‘Listen, this guy keeps coming to me, complaining about me all the time! Lock him up! I can't take him anymore, he's driven me crazy! Take him away!’ And we would take them away!” You see? Here is a psychiatrist who tells such things about his work.

In 1990, I spent a lot of time trying to have the psychiatric diagnoses of those who had received them overturned. People were on the register, but it varied. The nature of the illness that was recorded could be different. They could be removed from the register, but if a person was considered ill, they were treated, for example... There was a man named Volodymyr Hryhorovych Kravchenko. To his misfortune, he lived next to the family of the secretary of the Kharkiv regional party committee. They were even friends. But then their wives quarreled, one did something wrong, the other took offense and began to complain about him. He complained and complained until he was sent to a psychiatric hospital. Kravchenko even ended up in the Dnipropetrovsk special psychiatric hospital. I saw these documents myself; interestingly, the commission wrote for him: “to a special hospital,” and in the file, it was crossed out and written “to the Dnipropetrovsk special hospital.” Someone did this, you see? And Kravchenko spent a certain period there. Thank God, he survived. He had a weak heart; after the very first pill, he became very ill, and they stopped all these pills and simply “did not treat” him. He was a “robustly healthy” person, in fact. Absolutely healthy. It's very difficult to say he was sick. I'm not a doctor, of course... But they did remove his diagnoses. That is, back then, in 1990, I was able to get the diagnosis removed for about ten people, I don't remember exactly.

In the psychiatric hospital were Lyonya Plyushch, Mykola Plakhotniuk, Petro Ruban, and many others. In Russia—Petro Grigorenko, Natasha Gorbanevskaya, Lera Novodvorskaya, also many others. In general, we have compiled a list of these people, but there is still a lot of work to be done with it.

Anatoliy Koryagin

In this photo is Anatoliy Koryagin; he is directly related to this story. One of the dissident associations was the Working Commission to Investigate the Use of Psychiatry for Political Purposes. It was created back in the 1960s; it included Sasha Podrabinek, Slava Bakhmin. They had expert psychiatrists Leonard Ternovsky, Alexander Voloshanovich; I know them all. By the way, Voloshanovich's parents lived in Kharkiv; he used to visit here constantly. When he was about to be imprisoned, he chose to go to the West. He emigrated, lives in Britain, and has visited here with his English wife and children.

And Koryagin—a psychiatrist, a Siberian, came from there, defended his Ph.D. dissertation here, and worked in a hospital in Kharkiv. When there was no expert, he became the expert for this commission. That is, he examined people and wrote conclusions for them, that they were, for example, sane, or he didn't write it if he had doubts. When he felt he could not take responsibility and say that a person was sane, he did not write it. For example, he did not give such a certificate to Yevhen Antsupov. Although, in my opinion, Zhenya Antsupov was a sane person; he is one of the dissidents who received a sentence under Article 70 in Kharkiv.

Koryagin was not just an expert; he was a very active person. He went to the Dnipropetrovsk special psychiatric hospital. And there he was taken for an obvious KGB psychiatrist, because he was, you know, of Aryan appearance, so to speak—tall, handsome, blond, with steel-like, stern eyes. He was a tough man, in fact, stern. And Koryagin went to the Dnipropetrovsk special psychiatric hospital, and there they decided that a psychiatrist from a research institute in Kharkiv had come to inspect them. And he examined Nikitin, caused a real scandal. And his vocabulary was like that of a Komsomol member from the 1920s, only in reverse, like this: “Satraps! Stiflers of freedom! Executioners! What are you doing?! You are keeping sane people in a hospital! You, doctor, how could you?! And you, a Jew, you disgrace your nationality! You are keeping him in this hospital! That's it, I'm taking him away.” And he took him away. Koryagin took Nikitin, but then he himself was very quickly imprisoned, and Nikitin was returned to the very same psychiatric hospital. It's a rather sad story. And Koryagin received a 7+5 year sentence, endured terrible hunger strikes, very long ones. He had the health of four men; what was left was enough for one, you could say. He is about 1.85 meters tall, an athlete, a skier, a hunter, and a very physically strong man. And Koryagin lost weight down to forty kilograms in the c you could carry him in your arms. Thank God, he did not die, he remained alive.

There was another interesting institution—the fund for aid to political prisoners. It was established in 1974, after Alexander Solzhenitsyn received the Nobel Prize and donated all of it, a million dollars, to this fund. It was founded abroad. It also received other transfers for Solzhenitsyn's works, and other writers made charitable contributions to it. There were quite a lot of funds, and with these funds, they helped the families of political prisoners here, of whom there were thousands, as you have heard. There were certain rules, a certain technology. They reported on how these funds were spent, without naming names, and so on. The rules were as follows: 60 rubles per month were given for a child in a political prisoner's family; gifts were given for New Year's, birthdays, Christmas, and Easter. Funds were also given for a trip for a visit for the whole family. In addition, there was also a lot of things like food, clothes, and so on. There were named parcels. For example, many parcels went specifically to the family of Koryagin. He left behind a wife, a mother, and three sons; one was four years old, the second—ten, and the third—fourteen. And it was very difficult without him, but this help was substantial.

For all this to work, it was necessary, firstly, to somehow turn dollars in the United States into Soviet rubles in the USSR. Secondly, it was necessary to know the political prisoners, their families, addresses, so that people understood how to treat this, regarding information, and so on. To deliver this regularly, that is, it was necessary to have people, as they would say now, representatives of the fund in the regions, who somehow received all this, distributed it, reported, and so on. All this was not as simple as you can imagine.

Interestingly, the administrators of the fund were terribly persecuted, imprisoned one after another. Either imprisoned or pushed into emigration. Those who did this locally were, I would say, not imprisoned just for that. I judge by myself, because in the 1980s, while the fund existed, I was the only person in Kharkiv who was acquainted with all the families of the dissidents who were imprisoned in the city. And I simply received it and delivered it, distributed it around the city. These were Altunyan, Koryagin, the historian Yevhen Antsupov, Alexander Paritsky, Yuriy Tarnapolsky, Zhenya Aizenberg... It should be said that Jews did not particularly need this fund; they had their own fund, and a very rich one. That is, the help there was much greater than in this fund for political prisoners. But there were very many named parcels; they were simply sent.

The most difficult thing, you know what it was? To get these funds, to convert dollars into rubles. Because dollars—that was scary, Article 80, for which they executed people, as is known. The famous story of Rokotov, who was executed for currency speculation, introducing this article after he had already committed the crime. That is, violating the principle of the prohibition of the retroactive force of law. Therefore, it was very risky with dollars; it was done differently.

The first administrator of the fund in 1974 was Alexander Ginzburg. In February 1977, he was imprisoned when the repressions against the members of the Moscow Helsinki Group began; Ginzburg was also a member. After him, his wife Arina Zholkovskaya-Ginzburg was the administrator for some time. After she emigrated, Kronid Lyubarsky, Malva Landa, and Tatyana Khodorovich became administrators together. They were also pushed into emigration in the same 1977, and Sergei Khodorovich, the cousin of Tatyana Sergeyevna Khodorovich, became the administrator of the fund. He was the administrator for five years; he held on, but he did not engage in anything else, which was significant. All the others were engaged in many other things—public activities, signing letters, and so on. But Sergei—exclusively the fund. He held on for five years, but he was imprisoned as well. He had a very hard time in prison; he was thrown to the mercy of criminals, he was terribly beaten. A bad story, described in his memoirs, which are on the internet. After Sergei was imprisoned, the last administrator of the fund was the translator Andrei Kistyakovsky, the same one who translated Koestler's *Darkness at Noon*, the first translator of Tolkien. But he served for a very short time; special operations began against him, besides, he fell ill, he had cancer, and he resigned. It was the end of 1983, and there was no one in Moscow who would take it on, to our great regret. But even without that, funds were collected by pooling money for the families of political prisoners. I was involved in this myself throughout the 1970s, constantly.

All this ended in 1987, when all political prisoners were released. When “perestroika” came, the first thing Gorbachev did after the April Plenum of 1985 was to order a halt to all political cases, not to imprison anyone else, and to transfer the existing cases to the prosecutor's office, for example, not to reclassify from Article 190 to Article 70, so that there would be no new sentences. They understood well what it was. Gorbachev stopped this in 1985, and over two years it gradually faded away; there were almost no new sentences and new imprisonments, with rare exceptions. And then he and Yakovlev planned a mass release of political prisoners for the spring of 1987.

But, as always, the prisoners understand all this much better. Anatoly Marchenko began a hunger strike in August demanding the release of all political prisoners, fasted for 110 days, and died under mysterious circumstances, as if his heart had given out. He had already ended the hunger strike, Larisa was already preparing to go for a visit, and then the news came that he had died in the Chistopol prison. This happened on December 8, 1986. I will remind you that by that time the films *Repentance* and *Is It Easy to Be Young?* had already been released, the magazine *The 20th Century and the World* had already begun to change radically, and there was already *Ogoniok* with Korotych.

The world simply exploded after the death of Tolya Marchenko. And a week later, Gorbachev called Sakharov and said literally this phrase: “Andrei Dmitrievich, I ask you to return to Moscow and engage in your patriotic activities.” Sakharov didn't even have a telephone; there was a police post there, and it was impossible to get to him. Since May 1984, in Gorky. It was not even known that he was on a hunger strike; he was constantly guarded by policemen. When he went for a walk with his wife, there were cops in front, behind, to the left, and to the right, and that's how he walked. And it was impossible to approach; 18 people were detained who tried to somehow get to him. And then one day, they removed the policeman, installed a telephone, and Gorbachev called. A week later, on December 17, he was already in Moscow. And all this spun up very quickly, very quickly.

At the end of February—beginning of March 1987, there was a mass release of political prisoners. And a different period begins, not a dissident one. The first journals started. May 1987—the journal *Glasnost*, editor Sergei Grigoryants, June—Lev Timofeyev, the journal *Referendum*. In August 1987, *Express-Chronicle* began to be published—the first and only all-Union human rights newspaper. And it took off from there. And all this was no longer samizdat. It was all printed, print runs were ordered in the Baltic countries, transported, distributed, sold. All this was very fast, and one could talk about this separately, but that would be a different period, not a dissident one.

On this, I will put a period. I have tried to make this overview general, just to make it clear what the dissident movement was.

The last thing I want to say. After all hopes for something better were crushed in 1968, people faced the question: what comes next? Can we hope for anything at all? Can we expect anything from socialism? This company that was in the photo (Petro Grigorenko, Arkadiy Levin, Henrikh Altunyan, Vladyslav Nedobora, and Volodymyr Ponomariov), they all believed in socialism with a human face, and even then, after their release, they remained Marxists, by the way. They changed over a very long time. Henrikh Altunyan was the party organizer of his academy's course, a party member, and so on.

And then the question actually arose: what's next? And people began to understand that nothing particularly good could be expected. In samizdat, there were works, in particular, in which it was written that the economy would perish, and nothing good would come of it. There were quite accurate forecasts of how it would perish, that the Soviet Union would collapse. This was said in Amalrik's book *Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984?* And then some people who said to themselves, “There's nothing to do here, we have to leave,” emigrated. Some people who decided they wanted to stay here, stayed. And some people decided to adapt.

Marynovych formulates this as a conflict between the moral instinct and the instinct of self-preservation. The instinct of self-preservation dictates to close one's eyes and not see what is happening, and just live as one lives, to get pleasure from life. The moral instinct, however, dictated an understanding that what was happening was actually a crime against humanity, that the regime was inhuman, cruel, that it was impossible to coexist with it. The moral instinct effectively sent a person to fight this regime in one way or another.

Between these possibilities of conformism and dissidence lies a whole large spectrum of behavior of different people, who behaved differently. And one can tell many specific stories. For example, Drach and Korotych, the Sixtiers, famous poets, leaders—they adapted. They were members of the party, traveled abroad, became Soviet people. Lina Kostenko went into internal emigration, did not betray anyone. But, if she was a dissident, she did not act actively. Except for signing letters of protest, that she did. Others, like Svitlychny, Dziuba, Sverstiuk, effectively became dissidents. Dziuba, as is known, later repented, it's a complicated story, I won't go into it. But he didn't give anyone up, didn't betray a single person, didn't name anyone, unlike Krasin and Yakir. The rest went to the camps just for calling things by their proper names, as Sverstiuk said. Svitlychny, Sverstiuk, Plyushch, Antoniuk, Stus, Chornovil, and many others.

The spectrum of behavior was very wide. Some chose the fate of an internal émigré, some were more active. Some still tried to make a career in Soviet times, but without betraying their moral values. But, in fact, the situation is quite harsh. As a rule, in any person's life, there comes a moment when they have to choose between making a moral concession, giving up some Soviet benefits, or an immoral one—taking the benefits and betraying themselves and those around them. If they understood such things at all. There were also very many who understood nothing, who were far from this.

Something like that. Thank you for your attention.

Olha Riznychenko: You said you would calculate how many from Ukraine were imprisoned in total?

Yes, sorry, I'll tell you now. I give the figure of forty percent. Not only those who were imprisoned, but dissidents in general. I calculated this specifically. The number of prisoners. The thing is, we have a database of Soviet political prisoners. I simply traced through it how many were Ukrainians. Here I am talking only about Articles 70 and 190, our Article 62 and 187-prime. If you take these lists, forty percent there are Ukrainians, people from Ukraine, let's say. People from and those who lived in Ukraine. We compiled a list of people who were repressed for political reasons in the post-Stalin era; there are three thousand people there. Three thousand, if you take forty percent of them—that will be the total number (1:41:30).

Another interesting thing. At the founding congress of “Memorial” in 1988, where there were a thousand people, four hundred were from Ukraine. The same forty percent. If you take repressed writers—forty percent. It's amazing, but it's a coincidence. Therefore, I believe that forty percent is the correct figure. You see, no one calculated these things by republic. There are data on the general work of the KGB, so to speak, throughout the Soviet Union. But, if you approach the all-Union figures this way, I count—forty percent.

Professional historians do not agree with me. For example, Mykola Bazhan says that this is too much, actually less. I do not agree with him, I think it is not less. In fact—it's different. If you count all the religious believers, and if you take the proportion of Baptists among the population in Ukraine and Russia, then in Ukraine there are significantly more. And in general, there were more Protestants in Ukraine. In Ukraine today, there are 18 Protestant churches. And they were all repressed during Soviet times, except for the “correct” Baptists. All the others were under very great pressure.

Nelia Yakivna Nemyrynska also defended them. She gave me a large map of the Soviet Union with marks in the places where there were Baptist communities, where people were repressed. There are very many such marks in Ukraine. She knew all this, knew them all. In general, an absolutely phenomenal woman. Born in 1928, she died recently. She even managed to work with us in the early 2000s as a lawyer in specific cases of torture. Ten cases, she defended Mykola and Raisa Rudenko, twice Yosyf Zisels, Vitya Nekipelov, Bidiya Dandaron. There was also a man named Khudenko, the head of a state farm, a Hero of Socialist Labor, who was also imprisoned. He began to engage in things that were allowed later. By the way, there were very many such people; they were even nicknamed economic dissidents. The extent to which they can be considered dissidents is a question, but this is a separate group. Article 86, embezzlement on an especially large scale. There was its own rate: for a thousand rubles stolen—a year of imprisonment, above 15—execution.

Question from the audience: What was the diagnosis given in the hospital? Because I understood that they couldn't write down some non-serious illness. But if it's a serious illness, then there are serious drugs that can kill a healthy person, they can cause addiction. What was done to dissidents in hospitals and what diagnoses were they given?

In fact, not so much has been researched here that one could state something unequivocally. If you believe the published data that about two million people were removed from the register, then this is an extraordinary matter altogether. There was a recent publication; I was very surprised when it appeared.

Iryna Bahaliy: At that time, an instruction was issued that anyone who wanted to could be removed from the register. Everyone went and got themselves removed.

Yes, but how sick were they? That's the question.

Iryna Bahaliy: Some percentage was, of course, healthy.

Some were healthy, and some were sick. But I would not classify all of them as victims of punitive psychiatry. So, not much has been researched. If you take the people who were studied, from our circle, so to speak... Academician Snezhnevsky invented a diagnosis like sluggish schizophrenia. It was given to everyone in a row who was in psychiatric hospitals.

They treated them for real, as they treat schizophrenia, including with heavy drugs, and there were insulin shocks, many things. And indeed, those who came out after such treatment... Lyonya Plyushch was terrible, absolutely. For a time, he did not look like himself, could not communicate, and so on. There is a man named Vasyl Spinenko, he is an absolutely healthy person, he is still alive. He, an absolutely healthy person, became absolutely sick. For him, it comes in periods; he is sometimes sick, sometimes healthy. Mykola Valkov, whom I mentioned, was healthy, but he himself said that when he was being “treated,” he was in very bad shape. It also depends on the person's overall physical condition, how strong their body is, so that it can tolerate these heavy drugs and their after-effects.

Leonid Plyushch

They were released from there when they signed a pledge that they would no longer engage in what they had been doing; this should be emphasized. Otherwise, you might not get out. Plyushch is perhaps the only case where he was released after a general struggle for his release, which took place all over the world. This struggle was ramped up by his friends, primarily Arkadiy Levin, one of that Kharkiv four. They were all friends with him then, and later, until his death. Tatyana Khodorovich also did a lot for him, and many others. They mobilized literally everyone, and Plyushch was finally released. They decided that was enough, he was causing too many problems, let him emigrate. And he emigrated, lived in France. He got rid of all the consequences he had and was a completely normal person.

Still, those who were put there were sometimes absolutely healthy. Sometimes they were accentuators, let's say, accentuated personalities according to Leonhard. You could nitpick at them for some peculiarities of their behavior. In general, you know how Soviet people think: “Listen, anyone who goes against the Soviet government is insane. How can you do that? A normal person can't do that.” It couldn't fit in people's heads that someone could endanger their life, family, job, prosperity, everything they have and could have, and exchange it for a camp, for some kind of confrontation. It was hard for people to understand. And such an explanation, that he was just sick, was quite acceptable to them. It was also perceived in society without problems.

The main thing was to write the biographies of those people who ended up there, to pass them to the West. Zisels was very involved in this, but he did not advertise it; he did it secretly. It seems he compiled and passed on twelve biographies. He collaborated with this association. Books were written, *Punitive Medicine*. Sasha Podrabinek, Bakhmin, Peter Reddaway, an American who studied this topic. That is, they made this problem public, described specific stories.

And the most high-profile story of General Grigorenko, who underwent an examination in the United States when he arrived there, and it was concluded that he was sane and had been sane. Here, by the way, lies the problem of the rehabilitation of these people. Because for them to be rehabilitated, it must be proven that they are victims of punitive psychiatry. But I find it hard to imagine a psychiatric commission that would say about a person... You can say that they are now healthy. But that they were healthy when they were put in a psychiatric hospital—I think that is very difficult to determine, as a rule. But regarding Grigorenko, the Americans said that he was sane and had been sane. And this had very great consequences for the USSR.

The man I was talking about, Volodymyr Kravchenko, had a weak heart; he became very ill, and they stopped giving him those heavy drugs, and he survived. Besides, he ended up there quite late, already in 1985. He was there for a little over a year or a year and a half. But he was absolutely terrible when he got out. I met him after he got out; he somehow found me, and I handled his case. They removed his diagnosis, helped him with his various affairs, to re-socialize, so to speak. He was an absolutely healthy person.

Question from the audience: There is no dissidence now, so what is there?

That is another question, which is not part of my lecture's topic. In fact, dissidence was, is, and always will be. Because people who disagree with the current government have always been, are, and will be. The question is how the government perceives it. In Stalin's time, people were shot for such things. And they were shot without that. I saw a verdict in which it was written: “Passing by the NKVD building, he smiled mockingly.” 10 years of imprisonment.

In post-Stalin times, it was a so-called quiet terror. They repressed those who spoke out publicly, or were very stubborn and did not agree to stop their anti-Soviet activities. There was even such a decree, by which they were warned. That a person is warned to stop their anti-Soviet activities, which are not punishable by the criminal code. That's exactly how it was written. If they did not stop—they would be punished. And a warning under this decree was an aggravating circumstance when they were imprisoned. That is why everyone was given three years.

And now, we still have... True, one woman said: “the president is not immortal”—and she's already under suspicion. It's ridiculous, in fact, nothing will come of it. But, you know, some attempts to actually persecute people for their beliefs and statements have been constantly observed for all thirty years of independence. And one could talk about this separately. I think that there are a great many Soviet anchors both in consciousness and in practices. These Soviet vestiges that hinder our society. I think this is the main reason, honestly. I even wrote an article about this for the centenary of the October Revolution titled “Why Lenin Is Still with Us.” The Soviet way of thinking is very difficult and tenacious; it is very hard to get rid of.